The only content I want from my smartphone is for a specific type of waiting. When I’m in an elevator, it should half-hold my focus, not bewitch me enough that I get off on the wrong floor. It should pass the time without blinding my attention to the guiding automated voice of the SkyTrain. When I’m waiting in motion, I want content for a non-committal, meandering, distracted part of my mind, content that lets me go, “Uh huh, uh huh, uh huh,” without asking if I’m listening.

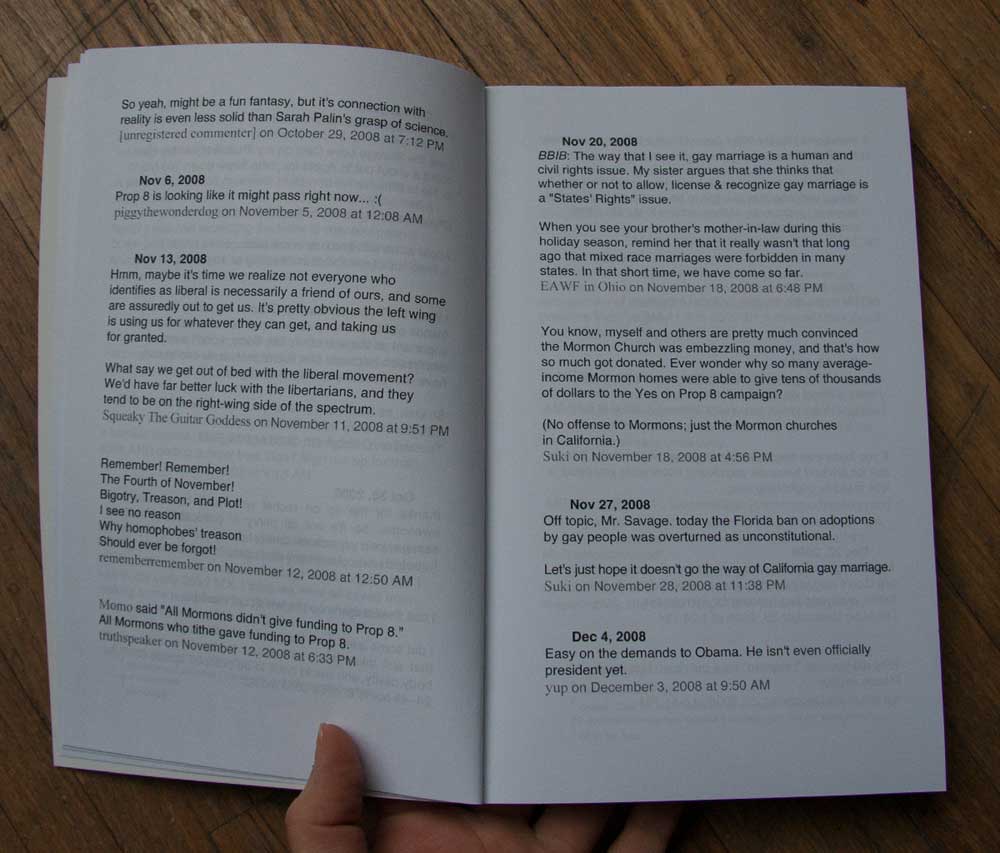

I’ve been reading Commentariat (2017), a new publication by Liz Knox, recently released with a small exhibition of her drawn portraits at Yactac. The book is a selective compilation of short texts gathered from the online comment threads of “Savage Love,” the weekly syndicated sex-advice column by author and activist Dan Savage. Knox gives us the date and time of each entry along with the commenter’s screen name, if they’ve registered one, and the corresponding article is represented only by its print publication date.

The compilation spans fall 2008 to the end of 2015, forming an imperfect chronology of North American sexual politics of the time. Commenters refer to notable events as they occur in the timeline—such as the passing and later dismissal of Proposition 8 in California, the overturning of the Defense of Marriage Act in the US, or the 2011 Canadian federal election. They respond to Savage’s column with praise or disapproval, and attempt to set each other straight with passionate appeals, articulating special insight or reckless hypotheses.

A page from Liz Knox’s Commentariat, 2017.

A page from Liz Knox’s Commentariat, 2017.

Knox’s deliberate disconnection of each remark from its immediate context forces unfillable gaps, shifting emphasis to the characters behind each screen name and away from the references within their ramblings. These characters differentiate through grammatical style, social comportment and political leanings, but they are unified as far as each is the type of person who engages in the exhaustive back-and-forth of an online forum. The graphite works on paper exhibited with the book at Yactac give a number of these characters form—simple line drawings portray Knox’s estimations of the faces behind “Hunter78,” “Hockey Mom” and “nocutename,” among others.

Commentariat produces a feeling of unease, largely due to its smuggling of the special volatility of online message boards into the quiet places that I bring books. The comments leap from screen to bound page, demanding an atypically linear reading of web content—I want to skim the paragraphs, scroll ahead or hit the back button. They also transport a sense of walking on eggshells, as though I may roll over to find “Taurean” in my bed, bellowing at me in ALL CAPS.

Kim Kennedy Austin, “Fast Girls Get There First” (installation view), 2017. Courtesy Wil Aballe Art Projects.

Kim Kennedy Austin, “Fast Girls Get There First” (installation view), 2017. Courtesy Wil Aballe Art Projects.

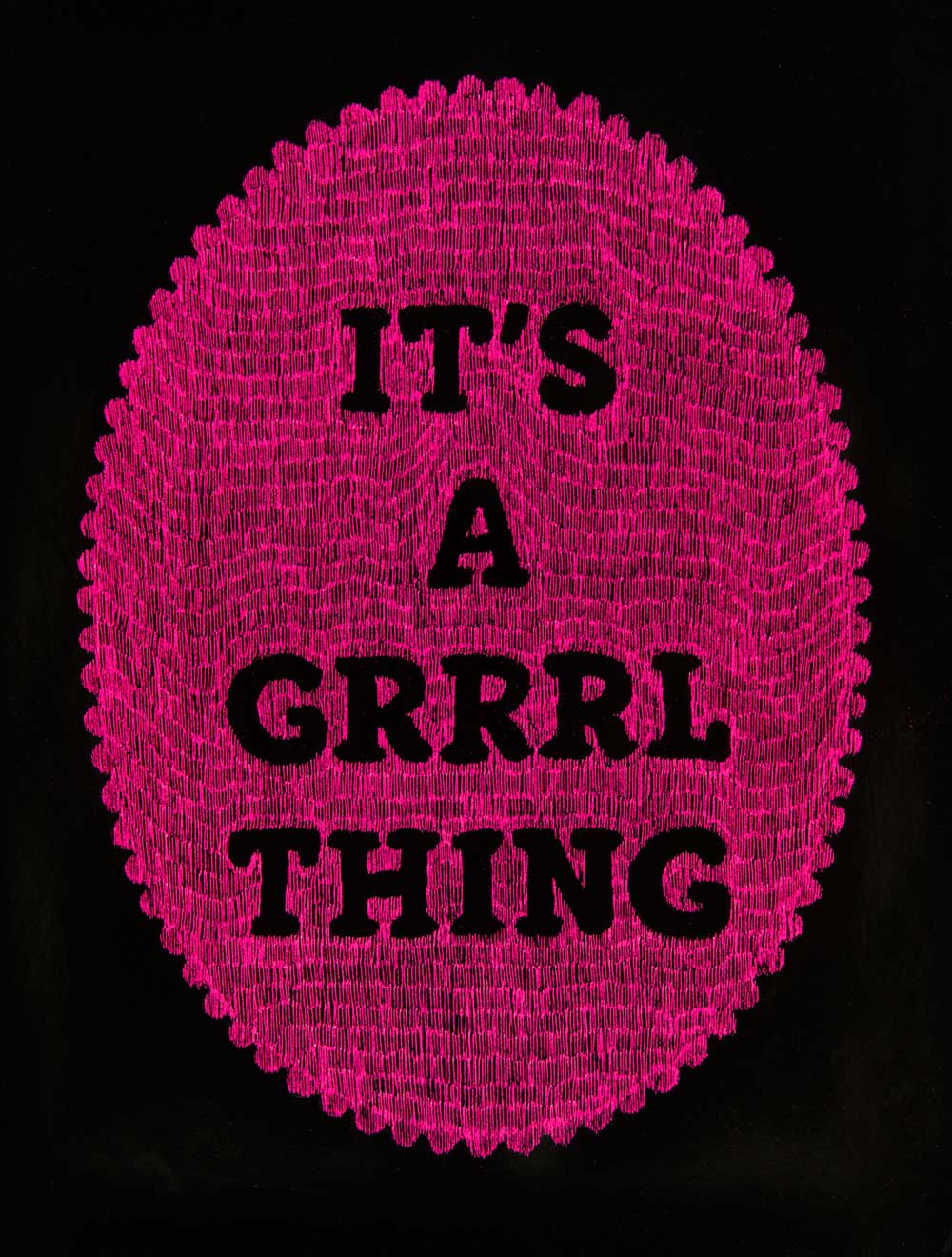

A second exhibition that grasps hold of generally disposable written matter is Kim Kennedy Austin’s solo exhibition “Fast Girls Get There First” at Wil Aballe Art Projects. It features text-based works rendered in materials marketed for hobby craft—brightly coloured fuse-bead compositions, and etchings on scratchboard. The artworks hang around the gallery in ten groupings of five, with each frame or panel presenting a short phrase lifted from the pages of decades-old issues of Seventeen magazine. Arranged together, they read like poetic verse: “What’s your big problem / Blush like you mean it / Put your feelings into words / Make your walk talk / Make like a rocket and flare.”

These artworks announce quips we seem to already know, employing homophones and puns to deliver commands and declaratives, made further benign through their willfully repetitive iterations. Fuse beads were originally patented for therapeutic intentions, and the obsessive seriality of these scratched, scalloped-edge ovals and marquise-like beaded shapes seems prescribed, as though the entire exhibition is an exercise in cognitive rehabilitation—like when a friend’s occupational therapist recommended he take up watercolour painting as a vapid, yet soothing, treatment for post-concussion syndrome.

Kim Kennedy Austin, “Fast Girls Get There First” (installation view), 2017. Courtesy Wil Aballe Art Projects.

Kim Kennedy Austin, “Fast Girls Get There First” (installation view), 2017. Courtesy Wil Aballe Art Projects.

Yet Austin’s vivid colour choices show awareness behind the ostensible dullness of each clichéd slogan. She draws us through the banal texts with a performance of tight scratch trails and intricate patterns. For whatever reason, she’s saying “look here”—perhaps to divert our attention from more painful reports.

Jeff Downer’s solo exhibition at Duplex, titled “Handsome Rewards” and part of Capture Photography Festival, uses as source material the sort of catalogues you would find in airplane seat pockets. They offer products that claim to solve problems you didn’t know you had—a blocking strip for that space between the stove and the counter, a wedge-shaped cheese grater with a sliding drawer, a beverage-sized side table.

Jeff Downer, “Handsome Rewards” (installation view), 2017. Photo: Capture Photography Festival.

Jeff Downer, “Handsome Rewards” (installation view), 2017. Photo: Capture Photography Festival.

Downer has skillfully assembled a scanned collection of found images equally evocative and laughable. Their studio settings amount to colourful backdrops that limit signifiers and contribute to a temporal ambiguity—the photographs were taken yesterday, or 30 years ago.

Without captions, several objects prove difficult to describe, requiring guesswork. Seriously, what is this? There’s a series of floating conical vases, basketball-net-like nasal inserts, and a woman wearing something that appears to be a combination wedding veil and mosquito mesh. Other objects, in comparison, are unnervingly simple—pairs of gloves, a roll of bright yellow paper towel and a flat, circular pillow. These ache for an informational sales pitch, but a blunt sans-serif over a garish yellow-to-red gradient provides a sole sweeping explanation: “It is just the thing for those times when every day seems the same.”

Downer’s formal strategies echo the novelty of his chosen content. His digital prints are pressed under charmingly convoluted Plexiglas panels that are fastened to the gallery walls with nails driven through orderly grommets. It’s a curious setup; yet even as I write this, I question whether the display technique is perfectly regular and has merely been alienated through its association to bizarre imagery surrounding it. Have I been hypnotized by printed matter better suited for takeoff and landing, or should Downer be filing a patent of his own?

Jeff Downer, “Handsome Rewards” (detail), 2017. Digital print. Photo: Capture Photography Festival.

Jeff Downer, “Handsome Rewards” (detail), 2017. Digital print. Photo: Capture Photography Festival.

Truthfully, I hate how crumbs fall in that space between the stove and the counter, but it’s only momentarily satisfying to invest in the fantasy of a perfect solution. Like the floorplans of condominiums I will never own in the advertising pages of the Georgia Straight, this content is most comfortably viewed while waiting for a bus, or for a receptionist to call my name. When it extends beyond these carefully limited contexts—if it sinks in—it contributes to a decidedly dreadful feeling, as though the real world is hastily sneaking past.

Lucien Durey is an artist based in Vancouver. His performative works engage with collections, found objects and ephemera.

Jeff Downer, “Handsome Rewards” (detail), 2017. Digital print. Photo: Capture Photography Festival.

Jeff Downer, “Handsome Rewards” (detail), 2017. Digital print. Photo: Capture Photography Festival.