In the early 1970s, Nathan Lerner entered the apartment of his reclusive tenant Henry Darger and came across a 15,145-page fantasy bookwork accompanied by hundreds of densely rendered watercolour paintings—many more than nine feet long and double-sided. Darger, who had been institutionalized at a Catholic mission before Lerner’s discovery and would die shortly after, was a longtime hospital janitor in Chicago and posthumously became one of the most celebrated figures of the Outsider Art genre.

Beyond the aforementioned epic, Darger produced three other manuscripts that together also topped 15,000 pages, and he collected thousands of pieces of ephemera. Yet it’s Darger’s largest bookwork and accompanying paintings—titled in full as The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion—that is best known today, tempering childlike innocence with the brutal carnage of war, and charting the activities of seven sister-princesses in an uncanny and fantastical landscape of Darger’s own invention. In the moment of Lerner’s discovery, I can only imagine how this herculean effort in storytelling must have appeared to unfamiliar eyes: the possibilities of narrative as boundless, exhilarating and deeply strange.

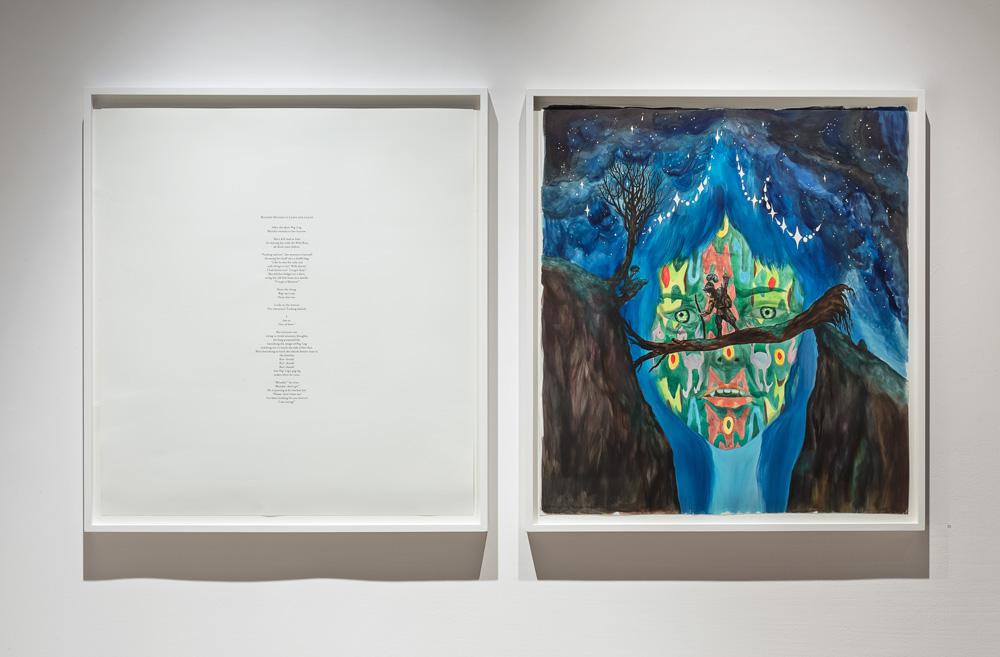

Shary Boyle and Emily Vey Duke’s artwork currently on exhibit at Oakville Galleries’ Centennial Square location, The Illuminations Project, shares many formal similarities with Darger’s oeuvre. After all, both involve the surreal and grotesque adventures of children, animals and their hybrids within a lush yet terrifying ecosystem. Yet it would be reductive to chart the similarities between these two practices on solely narrative grounds. Both projects involve a complex and evocative interplay between image and text, the creation of vivid imagery that refuses to remain a mere illustrative supplement to the written word. Both are dense efforts in myth-making that seem at once radically open to possibility yet resolutely honed in on the psyches of their creator(s), and both fundamentally understand that building new worlds takes time—more than 10 years for Boyle and Duke, and a lifetime for Darger.

The Illuminations Project is the result of a call-and-response exchange between Boyle and Duke that lasted for over a decade. Like a cross-media cadavre exquis, Duke began with a text that she sent to Boyle, who made two drawings: one in direct response to the initial text, kept private and to herself, and a second that was sent from Boyle to Duke to carry the story further. Duke then responded in a similar fashion: composing two new texts, one kept private and one returned to Boyle to continue the cycle. The resulting narrative ambles forward, led by text and image in equal turn. The Oakville exhibition marks the first time Boyle and Duke’s collaborative work has been shown in its entirety—both the initially shared and initially private creations alike—and gallery visitors are provided with a directed floor plan, inviting them to walk alongside their world and absorb all they can.

Like many stories before it, The Illuminations Project begins with a call to arms and ends with an elegy. Duke’s first text, The Birds and the Beasts Were There (for William Cole)—“Rats and snakes and fearsome creepers / who, at night, will start / the Grand Rebellion, creeping hellions: / my heart’s with your hearts!”—pairs well with Boyle’s image of a rag-tag band of creatures marching forward beneath thunderous gray clouds. Also in that first image: a wild, naked girl with patchy skin and messy hair rides on the back of a menacing warthog, giant birds and butterflies dodge lightning bolts in the sky, and a frog stands on two legs and carts along a giant human heart, pulsing with vivid purples and blues.

Boyle’s images only grow more dense, abject and delicately rendered throughout the exhibition: a woman receives oral sex while lying on the back of an elk, a three-tiered birthday cake dripping down her stomach; humans feverishly copulate with candy-coloured horse-human hybrids in a dark river that emerges from the mouth of a crone; tiny, ghostly figures crawl up a volcanic slope, seeking shelter within the gaping, quivering mouth of a giant conch shell at its peak. Even without reading the corresponding texts, Boyle’s images tell a story of charged anxiety and ecstatic release.

The Illuminations Project loosely follows young Bloodie, named for the menstrual blood dripping down her leg, and her dealings with Peg-Leg and his group of Wild Boys. Bloodie has a Mission, an indeterminate raison d’être that leads her through Boyle and Duke’s surreal world. As in many childhood relationships, Peg-Leg alternates between roles as Bloodie’s tormenter, champion and accomplice, and when they reconvene as adults, the two set aside differences and become companions until their end of days. The narrative ends with Duke’s elegy for Bloodie and Peg-Leg, returning to the earth that made them. In this elegy, she writes, “They die, and within hours / their collapsing tissue / begins to combine / with the earth they so loved. / The soil then issues forth a brood of / ruddy Lilliputians who/ ravenously, but gently, / devour their parents.”

Yet Bloodie is no lonely princess in need of a hero. Boyle and Duke’s narrative carries an uncompromising feminist streak that is visceral, declarative and wholly infectious. There’s the mother-daughter terrorist team narrated by Duke, stockpiling weaponry in order to topple “seats of phallic power.” There’s the pack of feral girls preparing to exact revenge on a cruel god: “We know / what you did / to Mrs. Douglas/ […] We warned you / we would come / with dogs.” And there’s Bloodie and Peg-Leg’s joyously crass epitaph, the final words of The Illuminations Project in its entirety: “THEY WERE FEMINIST AS FUCK.” For Boyle and Duke’s women to survive in this brave new world, they match its violence with their own unapologetic wrath, while remaining fully open to the terrible and exhilarating pleasures it can offer.

As Nathan Lerner and his wife Kiyoko pored over the countless pages of written, drawn, traced and collaged material in Henry Darger’s apartment soon after its discovery, I can only imagine they must have felt both an intense closeness to their solitary tenant and a frustrating lack of access: Who was this person, really? What compelled him to create these stories? Boyle and Duke are no outsider artists, to be sure, but that felt blend of closeness and distance pervades a viewer’s experience of The Illuminations Project. Standing at Oakville Galleries, I’m at once viscerally connected to Bloodie and her tribulations, yet Boyle and Duke’s narrative twists and turns frequently stretch beyond my understanding. Inevitably, this keeps things interesting.

As collaborators, Boyle and Duke were also undoubtedly navigating these gaps in interpretation between themselves. Creative disunity is integral to the collaborative process and provides a compelling edge to The Illuminations Project. One can only speculate over the narrative paths not taken, the symbols lost in translation between Boyle and Duke’s personal mythologies, the miscommunicated cues between image and text. As tightly knit as their aesthetics and worldviews appear throughout this project, the limits of Boyle and Duke’s shared vision remain a driving force throughout the exhibition at large. Ultimately, Bloodie’s story is at its most engrossing within the gaps between image and text, between Boyle and Duke, between the exhibition and myself. It’s the realm of sheer possibility, in all its perverse and beautiful forms.