It feels eerily fitting to write about Sharona Franklin’s exhibition “New Psychedelia of Industrial Healing” just as the new coronavirus has become a global crisis. Healing is on most people’s minds right now: Who will get sick? Who will be able to heal? What procedures, what infrastructure can we mobilize to that end? There’s something surreal, if not quite psychedelic, about living at the onset of a pandemic—it requires many of us, at least, to rethink what we’ve meant by health, vulnerability, sociality and care.

Sharona Franklin, Mycoplasma Altar, 2020. Gelatin powder, daisies, foraged rose thorns sourced by Wretched Flowers, baby’s breath, juniper berry, metal nuts, kidney beans, amoxicillin pills, hydroxychloriquine pills, methotrexate pills, antibodies in glass syringe vials, tapioca pearls, sunflower seeds, metal button, almond extract, papier mâché, wood, acrylic and plaster, 84 x 43 x 43 cm.

Sharona Franklin, Mycoplasma Altar, 2020. Gelatin powder, daisies, foraged rose thorns sourced by Wretched Flowers, baby’s breath, juniper berry, metal nuts, kidney beans, amoxicillin pills, hydroxychloriquine pills, methotrexate pills, antibodies in glass syringe vials, tapioca pearls, sunflower seeds, metal button, almond extract, papier mâché, wood, acrylic and plaster, 84 x 43 x 43 cm.

At the centre of Franklin’s concise exhibition is Mycoplasma Altar (all works 2020), a transparent, safety-cone-shaped gelatin sculpture filled with a variety of carefully arranged items: yellow daisies, kidney beans, methotrexate (an immunosuppressant) and amoxicillin (funny to realize I’m allergic to this artwork) pills, tapioca pearls and syringe vials filled with antibodies, to name a few. Mycoplasma Altar is also the first of Franklin’s jellies to use a (fungal) mould inhibitor—in part because she hasn’t had to sustain the others for the entire duration of an exhibition. But the work isn’t totally fixed; it shrinks a little every day, the curved edges at the bottom gradually curling away from the drippy silver pedestal beneath it. While most of her jellies and cakes feature healing herbs and flowers in enticing pastel hues, Mycoplasma Altar resembles nothing so much as a 1950s dinner-party gelatin mould, the dusty yellow color of it like a sun-bleached page in a midcentury women’s magazine. That visual association with the 1950s feels fitting, given the pharmaco-capitalist approach to the human body that began taking hold in that era.

Installation view of Sharona Franklin, "New Psychedelia of Industrial Healing," King's Leap, New York.

Installation view of Sharona Franklin, "New Psychedelia of Industrial Healing," King's Leap, New York.

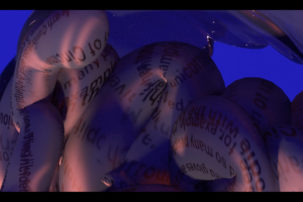

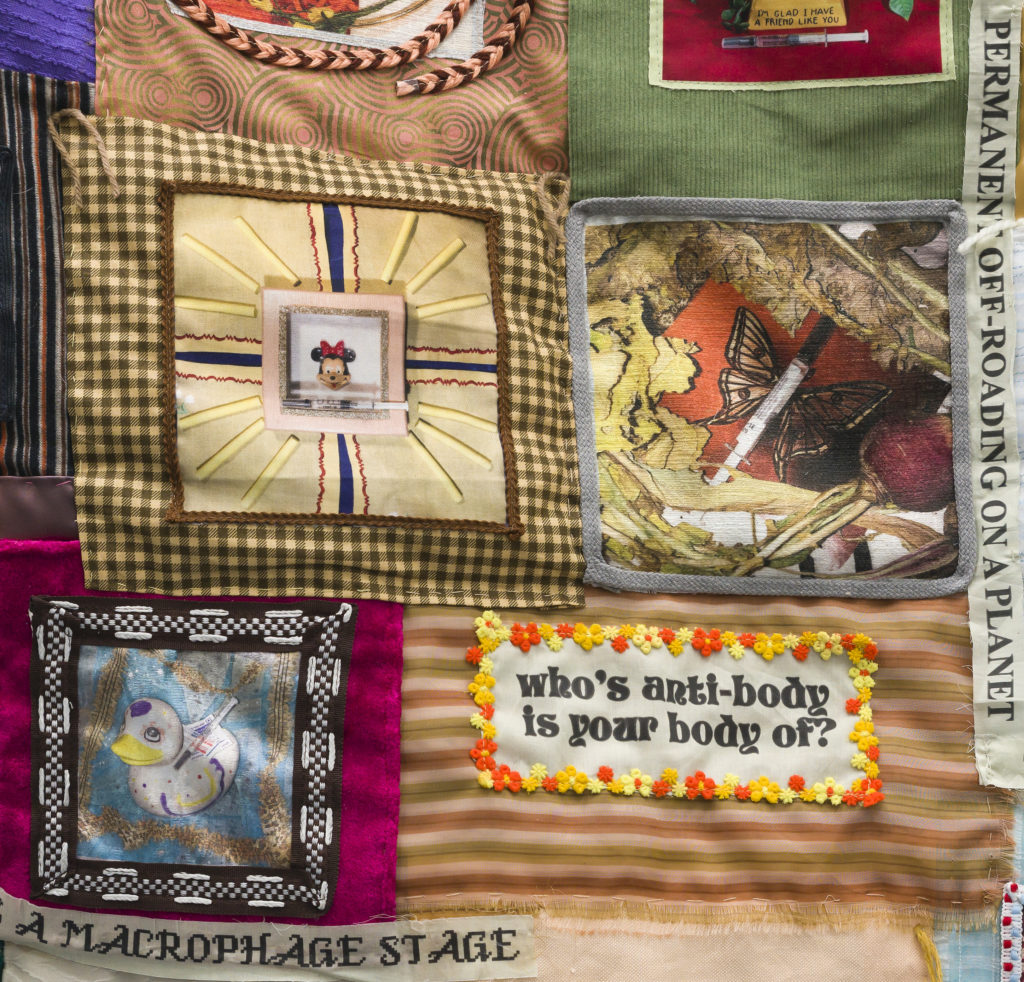

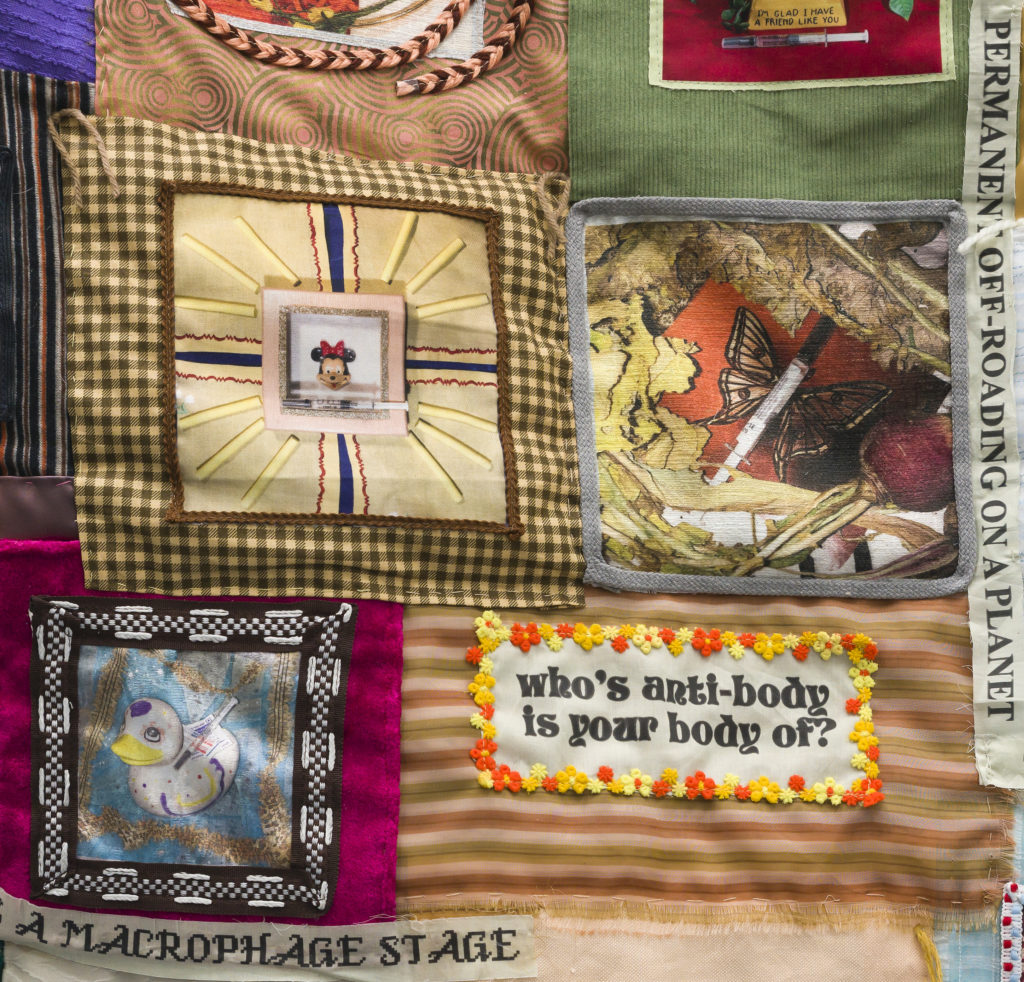

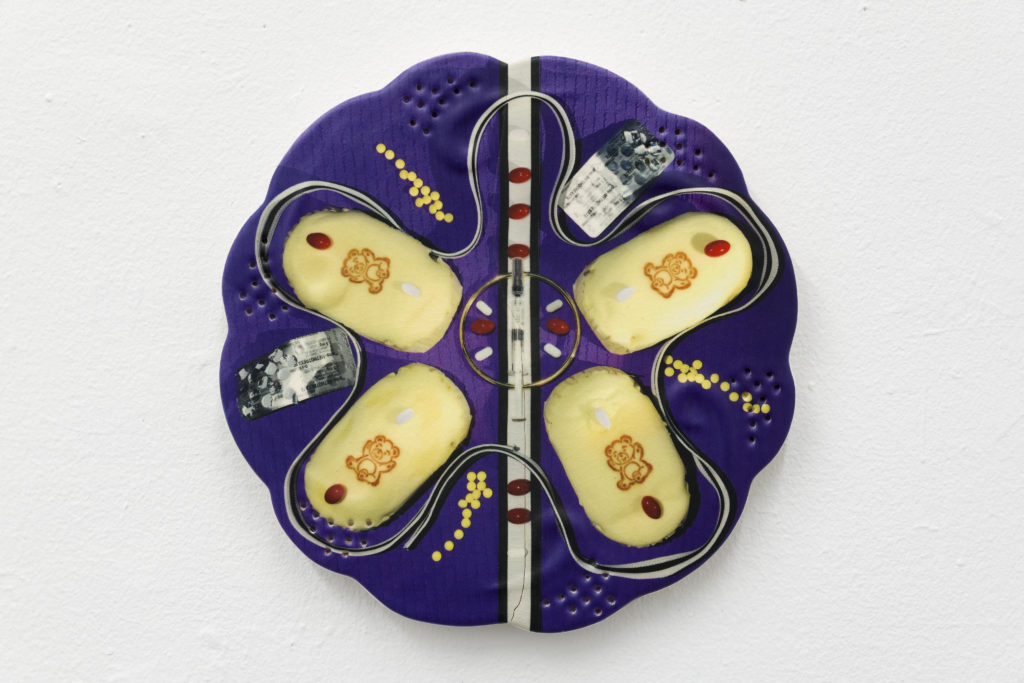

The other works in the exhibition all feature images from a series documenting syringes of a new biopharmaceutical immunosuppressant medication for rare diseases in the moments between Franklin removing them from the fridge and injecting them into her body. The largest, a patchwork quilt that hangs from the ceiling by a goalpost-shaped support, comprises a number of these images and others collaged on found fabrics; brief aphoristic texts about illness and corporeality—“PITY IS A SIN GREATER THAN ANY SICK-NESS,” “who’s anti-body is your body of?”—are scattered across the quilt itself and line the hanging support. Titled Comfort Studies, the work brings pharmacology into the home and the body at once, suggesting that viewers might find solace, rather than fear, in the permeability of both. Two wall-mounted ceramic plates, Hemichrome Plate and Amoebic Self Portrait of Pharmaceutical Preservation Methodologies, each host another printed image from the series, driving home the entanglement between the pharmaceutical and the domestic. In the former, a bright knit blanket undergirds a syringe resting on a clear plastic high heel, all framed by genetic terminology; in the latter, an assortment of pills and little yellow cakes printed with teddy bears form a kaleidoscopic pattern.

Sharona Franklin, Comfort Studies (detail), 2020. Cotton, linen, velvet, silk, polyester, vinyl, wood and plastic, 183 x 141 cm.

Sharona Franklin, Comfort Studies (detail), 2020. Cotton, linen, velvet, silk, polyester, vinyl, wood and plastic, 183 x 141 cm.

Despite the professionally printed images and the technology required to synthesize the medications they depict, these works evince a handcrafted aesthetic—an unexpected approach to the pharmacological, in which one expects every material to be pure and precisely measured, every surface smooth and sanitized. Their appearance links them to the ’70s psychedelia of the title, and to the work of artists from that era, such as Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt, whose trash-and-tin-foil altars memorialize the strange sacredness of the everyday, and Ree Morton, who integrated text into works that explore the affective and gendered dimensions of craft. I am reminded, in particular, of Morton’s The Plant That Heals May Also Poison (1974), with the work’s titular adage emblazoned on a wall-mounted celastic banner: that which cures us can harm us, and the products of a system that kills us can also keep us alive.

Sharona Franklin, Amoebic Self Portrait of Pharmaceutical Preservation Methodologies, 2020. UV print on glazed ceramic, 25 x 25 x 5 cm.

Sharona Franklin, Amoebic Self Portrait of Pharmaceutical Preservation Methodologies, 2020. UV print on glazed ceramic, 25 x 25 x 5 cm.

Sharona Franklin, Hemichrome Plate, 2020. UV print on glazed ceramic, 30.5 x 28 x 5 cm. All photos courtesy the artist and King’s Leap, New York. All photos Stephen Faught.

Sharona Franklin, Hemichrome Plate, 2020. UV print on glazed ceramic, 30.5 x 28 x 5 cm. All photos courtesy the artist and King’s Leap, New York. All photos Stephen Faught.