Political paradigms always end up replicated in the personal lives of individuals. Culture wars, transactional relationships, punitive self-interest: social media has long acted as a pressure valve for all of it, but this pandemic has increased the tension. Right now we are living through something, the material transitional power of which we won’t know for a while. The internet has stepped in as our primary social and cultural mediator in a way we have never experienced. This is a time to think about utility and value: what the internet really does for us, how we consume art and what exhibitions mean in framing that experience.

Curated by Lorna Mills, Faith Holland and Wade Wallerstein, “Well Now WTF?” is an online exhibition that responds to the abrupt closure of art institutions worldwide. It includes more than 100 Canadian and international artists whose practices involve moving image. The title effectively registers the poignant, ambient dread of being in the world—a dread that has been recently pushed to the foreground. It incorporates an array of digital art aesthetics to address these feelings, showing the digital—and Net Art in particular—as a responsive tool.

I began thinking of the history of the net, and of art on the net in turn. The internet moves faster than life offline; we may often sense that technology alters cultural and political landscapes, but I would say it is the other way around. It has been a long time since the internet was separate from the offline world, and our acceptance of this parallels certain shifts toward always working, always watching and always being watched.

Browser view of “Well Now WTF?,” an online exhibition curated by Faith Holland, Lorna Mills and Wade Wallerstein. wellnow.wtf

Browser view of “Well Now WTF?,” an online exhibition curated by Faith Holland, Lorna Mills and Wade Wallerstein. wellnow.wtf

For “Well Now WTF?” to return to the GIF as artistic medium is a rebuttal of the post-internet era and its attendant archetypes. There is something distinctively chaotic about early web aesthetics, and GIFs in particular—much less streamlined and serious than the sensibilities of art on the internet that followed Web 2.0 and social media. Lorna Mills and Faith Holland have long produced art that is online first and online only, even as the past decade saw these aesthetic parameters supplanted by those of the post-internet, which translated digital artifacts into gallery spaces along with all the trappings of a neoliberal internet culture.

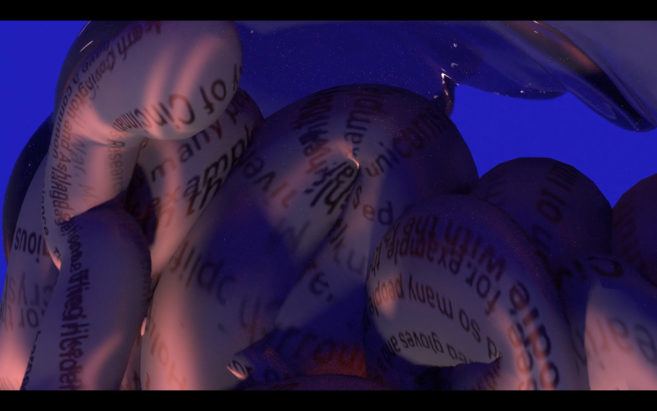

Clusterfuck Collective, Very Good Morning Kaffe, 2020.

Clusterfuck Collective, Very Good Morning Kaffe, 2020.

Early Net Art embodies a time when the internet was experimental, less truncated and less professional. It revels in its sensory overload and non-catharsis—just an infinite loop of activity. More recently, before the pandemic, online exhibitions increasingly characterized digital art as fashionable objects for more experimental collectors. By contrast, “Well Now WTF?” is conceived more as homage, celebrating a previous era of the net and its more accessible tools.

Collections of GIFs are separated into rooms with titles such as “Bed of Nails,” “Clusterfuck Closet” and “So Sad Because the Art Fairs Were Cancelled,” contexts that vacillate between humour and seriousness. The curators express that these spaces are not organized thematically, but intuitively. Ellen.gif’s work, a pool of glittery slogans on mindfulness and gratitude, is reminiscent of 2000s blog décor while also reflecting a current positivity culture that reprimands the slightest wanderings into cynicism. Similarly, Clusterfuck Collective lists the five stages of grief in sparkling fonts and superimposes them over a landscape of rolling hills at sunset, codifying a whitewashing of negative emotions for an idealized world.

In the “Deep Dark Germ Corner” exhibition room (a playlist of YouTube videos), Alice Bucknell’s E-Z Kryptobuild (Promo and Backstage) (2020) stands out. A satirical promotion video complete with the empty vernacular and ostentatiousness of utopian real estate projects, it illustrates what the mega-rich imagine their money will ultimately buy them—that is, an exclusive opportunity to escape the ravages of climate change and contagion while the rest of us suffer. After the promotional script is delivered, Bucknell’s narrator vents frustrations “backstage” that cut to the heart of what we’re experiencing now, as we are all more closely confronted with how catastrophe is stratified: “It’s the same as it’s always been. No one really cares until shit really hits the fan, when our slow apocalypse speeds up”—when the call to act can no longer be ignored.

Alice Bucknell, E-Z Kryptobuild (Promo and Backstage) (still), 2020.

Alice Bucknell, E-Z Kryptobuild (Promo and Backstage) (still), 2020.

Our concerns have abruptly shifted to how we conceive of caring for ourselves and others in a period of mandated isolation like this one. Libbi Ponce’s getting better, excerpted from a 2018 work, uses the now-mainstream rhetoric of therapy and self-care; someone spreads green gel on skin while a slowed, low-pitched voice recites phrases of validation and positive reinforcement. Right now, the terrifying reality of being alone with ourselves and our thoughts edges closer, and these might be things we’d like to hear. But deployed and consumed over social media, these aesthetics often function as band-aids over real disaffectedness, and their veneer of meaningfulness tends to wear off quickly.

There is a fog to break through in writing about the ineffable and a collective mood, which is rather thick at the moment. I am drawn to part of the title of a 2016 work by Korakrit Arunanondchai and Alex Gvojic: There’s a word I’m trying to remember, for a feeling I’m about to have. Physical closeness has been replaced by noise. Well, now what? What is to be done? Corporations are emailing to say we’re all in this together. But the full extent to which this statement is true is completely lost on any company and its PR language. And what about the extent to which an online exhibition can make someone feel less alone in a pandemic? Maybe we can decide that together.

Ellen.gif, 2020.

Ellen.gif, 2020.