The art exhibitions I’ve been attracted to in Montreal recently engage in intergenerational discussions that range in scope from broad to deeply intimate, and each in their own way herald a reckoning. The following exhibitions propose different approaches to that dialogue: artists from different generations talk to one another in the present; they commune with past selves; they reinterpret the histories of family and place. These exhibitions go beyond nostalgia and, in the discrepancy between present and past, they create a response to the current moment. I was struck by their investment in various forms of reexamination, whether it was of community, memory, land or the self. The artists culled from history to determine what, if anything, should be brought into the now, and it is this reconsideration of the past that placed these shows squarely in the present.

Maria Hupfield, “The One Who Keeps On Giving,” 2018. Installation view at Galerie de l’UQAM. Photo: Galerie de l’UQAM.

Maria Hupfield, “The One Who Keeps On Giving,” 2018. Installation view at Galerie de l’UQAM. Photo: Galerie de l’UQAM.

Maria Hupfield’s exhibition “The One Who Keeps on Giving,” curated by Carolin Köchling, has been on a nationwide tour since its debut at the Power Plant in Toronto last winter. The Montreal leg of the tour was presented from January 11 to March 3 at Galerie de L’UQAM, tucked in a quiet corner of the university’s otherwise busy downtown campus. The exhibition featured sculptural pieces and video work by Hupfield, originally from the Wasauksing First Nation and now living in Brooklyn.

The exhibition was split into three spaces. Four wood plinths stood in the centre of the first space, each with various objects recast in felt, including a hat, a pair of boots, a cassette tape and headphones, lit overhead by a cluster of lightbulbs. The recasting of these objects in felt divorced them from their functionality. The felt’s neutral grey palette equalized the objects, rendering none more useful or valuable than another, and the fuzzy texture gave each object a warmth that would have been lost had Hupfield worked with a less tactile material. Their forms seemed like memories: warm yet uncanny, particular yet a little but blurry. Each object became a vessel to communicate with the past.

Maria Hupfield, “The One Who Keeps On Giving,” 2018. Two single-channel video projections, colour, sound, 15 minute loop each, dimensions variable. Installation view at Galerie de l’UQAM. Photo: Galerie de l’UQAM.

Maria Hupfield, “The One Who Keeps On Giving,” 2018. Two single-channel video projections, colour, sound, 15 minute loop each, dimensions variable. Installation view at Galerie de l’UQAM. Photo: Galerie de l’UQAM.

The exhibition’s second space contained the show’s centrepiece. To make it, Hupfield and her siblings staged performances in response to Georgian Bay (1974), a painting depicting the Georgian Bay shoreline by Hupfield’s mother Peggy Miller. Two recordings of these performances were projected on opposite walls facing one another. The recordings played one at a time, so as one ended you had to turn yourself around to view the next. Each performance followed roughly the same sequence: the painting was unveiled from a felt blanket and considered by each performer before they began their response. Then they danced. One sibling began to sing, her voice kept in time by the beat of a drum. Another held the painting (in one version the canvas was faced toward the viewer; in the other the painting was turned away). Similarly to Hupfield’s felt objects, the painting acted here as a portal into the past, a vessel through which each performer bodily manifests intimate environmental and interpersonal memories. This allows them to communicate with their mother on their own terms and creates a cross-generational dialogue, like siblings squabbling over the details of an old family legend passed down through the years. The inexact mirroring of each recorded performance underlined the fallibility of memory: how no single moment can be reconstructed the same way twice.

Serge Murphy, Le monde plate-forme, 2018, and Jean-François Lauda, Sans titre, 2017. Installation view at the Guido Molinari Foundation. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

Serge Murphy, Le monde plate-forme, 2018, and Jean-François Lauda, Sans titre, 2017. Installation view at the Guido Molinari Foundation. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

A different cross-generational conversation takes place across town in the form of “Joueurs,” an exhibition on at Hochelaga’s Guido Molinari Foundation until April 22. “Joueurs” features work by Serge Murphy, an established multidisciplinary artist, and Jean-François Lauda, an emerging self-taught artist. They present an offering at the gallery’s entrance: Lauda’s large canvas, layered with greens, blues and purples, hung behind a yellow plinth that displays Murphy’s small, unassuming sculpture of an archway made from clay, plastic and styrofoam. Lauda’s abstraction broods next to Murphy’s lighter sculpture. The difference in scale and tone between those first two pieces come to define each artist’s approach in the rest of the exhibition.

On the ground floor of the show, a series of Lauda’s notebook-sized watercolours span a wall, and another large abstract painting hung on the adjacent wall like a one-sided bookend. Across the room stands a number of multicoloured plinths that displayed Murphy’s sculptures, each made from a variety of repurposed materials including wood, plaster, wire and cardboard. Facing the plinths was a wall of wooden planks and cardboard painted with colourful stripes that stretched up towards the ceiling. Upstairs, more of Murphy’s sculptures sat scattered across the floor. The exhibition was busy, but the chaos was thoughtfully arranged so as not to feel cluttered.

Exhibition view of “Joueurs” with works by Jean-François Lauda at the Guido Molinari Foundation. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

Exhibition view of “Joueurs” with works by Jean-François Lauda at the Guido Molinari Foundation. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

As its title suggests, “Joueurs” is an opportunity for Murphy and Lauda to play with material, form and arrangement. The sculptures are playful but not without reverence for the materials used; this is evidenced by the careful placement of each of the sculpture’s parts. It is as though Murphy was in communion with a younger self while building these, his almost anthropomorphic sculptures being like long-forgotten imaginary friends made real. It is refreshing to see an artist so established allow himself to become a kid again with such little pretension. Lauda’s large-scale paintings are layered with colour, the traces of earlier experimentation visible underneath. Lauda’s abstractions are skilful, but occasionally the grandness of the paintings feels at odds with the otherwise whimsical exhibition. Perhaps Murphy could tap into that sense of play because a long and successful career as an artist has allowed him to take his work less seriously. To keep up with Murphy’s exuberant energy would be a challenge for any artist, and by no means is Lauda entirely unsuccessful. His watercolours, with delicate lines that lightly bruise the page, show indications of an artist with the capabilities to approach painting with the deft and playful touch of artists who have preceded him. “Joueurs” stages a conversation between artists at different stages in their careers, and in an ironic role reversal, it is the older artist who seems to encourage the younger one to loosen up.

Douglas Curran, In Advance of the Landing: Folk Concepts of Outer Space, 1981. Postcards. Artexte’s collection. Installation view at Artexte. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

Douglas Curran, In Advance of the Landing: Folk Concepts of Outer Space, 1981. Postcards. Artexte’s collection. Installation view at Artexte. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

“Outside: Performing the Sovereign and the Foreign at Quebec’s Border,” an exhibition curated by Adam Kinner at Artexte from January 17 to March 10, combined photography, performance and research collected from the gallery’s archives along with Kinner’s own audio and performance work. The show, spare within Artexte’s small gallery, provided a quiet space for contemplation; if “Joueurs” is a playground, Kinner’s exhibition was a library.

In I asked students in my French class to read a text by René Lévesque (2017), an mp3 player contained six voice recordings of French-language students, each new to Quebec, as they read an excerpt from Lévesque’s Option Quebec, one of the foundational texts of the Quebec sovereignty movement. Kinner then transcribed each of the recordings into musical notation, which hung on brown paper across one gallery wall, the unique cadence of each voice captured in a way that could, theoretically, be copied. The piece exposed the performative nature of a Quebec national identity, its porous borders often obscured by a pure laine narrative. Rather than present Quebec citizenship as something inherited through colonial bloodlines, Kinner offers national identity as something one learns, like a song on a piano. On another wall, Kinner arranged a 1981 photo series by Douglas Curran that contained twelve postcards of UFO enthusiasts standing next to their homemade UFO replicas. Adjacent to this display hung Kinner’s single photograph of the US/Quebec border, the mythology of Area 51 evoked by a menacing sign on an otherwise desolate road.

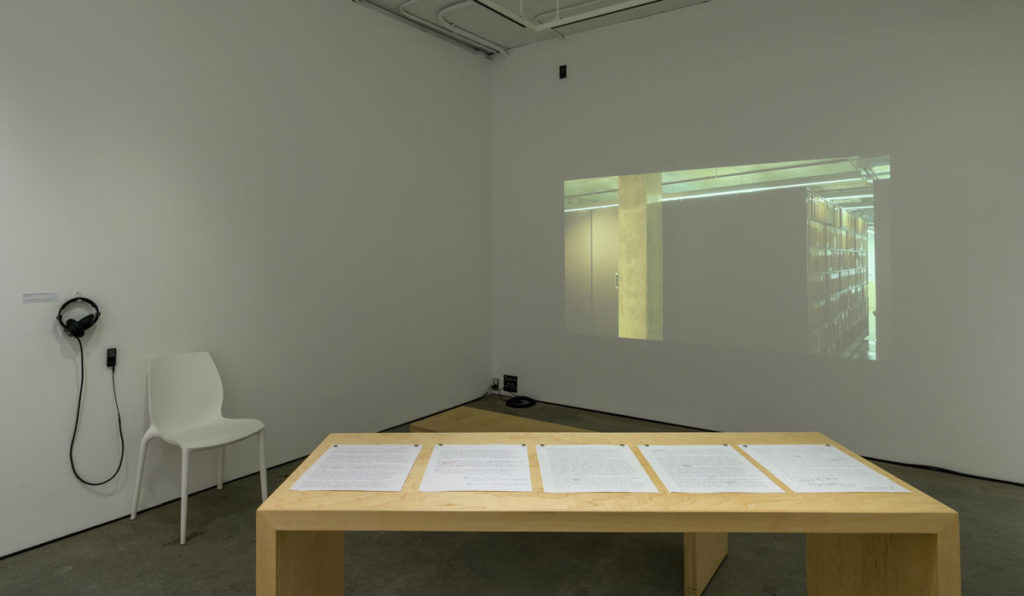

Adam Kinner, “Outside: Performing the Sovereign and the Foreign at Quebec’s Border,” 2018. Installation view at Artexte. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

Adam Kinner, “Outside: Performing the Sovereign and the Foreign at Quebec’s Border,” 2018. Installation view at Artexte. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

Running between the Leonard and Bina Ellen Gallery, SBC Gallery and VOX (2018) is referred to in the exhibition text as a cover of a 1971 performance piece by Françoise Sullivan. The audio recording captures the sound of Kinner and collaborator Vincent Bonin as they run along Montreal’s Rue Sainte-Catherine. In Collection/lights, Kinner filmed the Artexte archive and its surroundings to create a portrait of the gallery’s inside and outside. An annotated early draft of Denis Lessard’s 1989 text “Dance into Performance,” which discussed the intersection of dance and performance art, was spread out on a table in the centre of the room. The body is the lacuna in these pieces, invoked but not presented. Bodies permeated the gallery like ghosts, their presence recalled through audio, text and theory, but their representation remained notably absent, which allowed Kinner to facilitate a conversation about the borders of national identity across time and space. Through a mix of archival material and original work, Kinner generated a call-and-response with the past, its unresolved echo carrying beyond the gallery’s walls.

Each of these exhibitions, in their own way, has conducted a dialogue with the past to reflect a present moment. This method of transtemporal communication is critical. Murphy’s sculptures show how it can disentangle an artist from their ego, Hupfield demonstrates how it can also connect their work to a broader lineage and Kinner allows it to situate their practice within a broader political history. In each case, the artist has had to respond to history in order to ground themselves in the now.