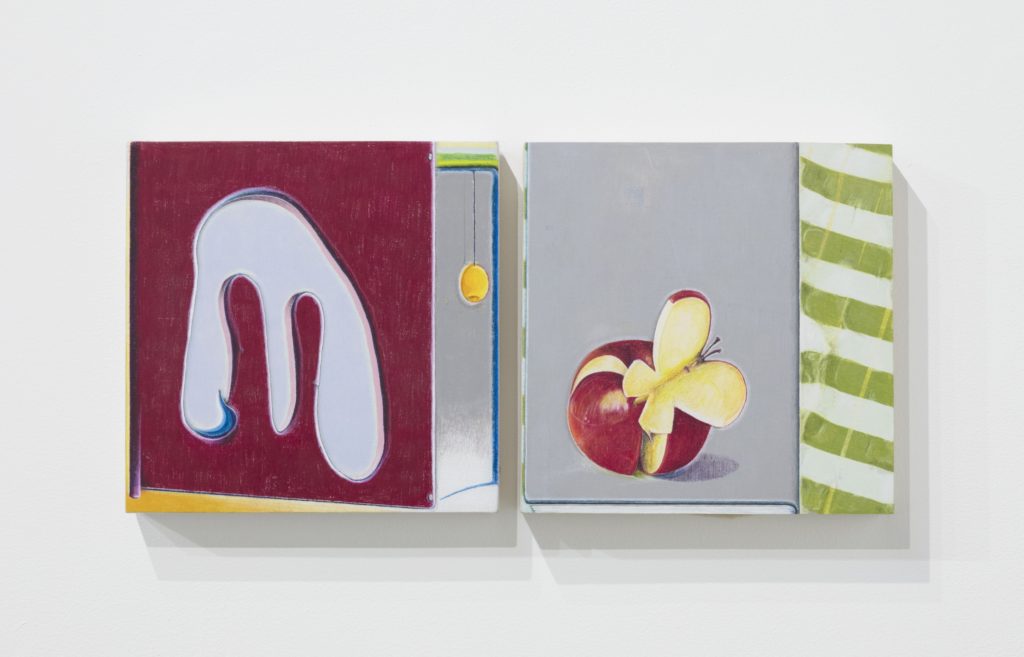

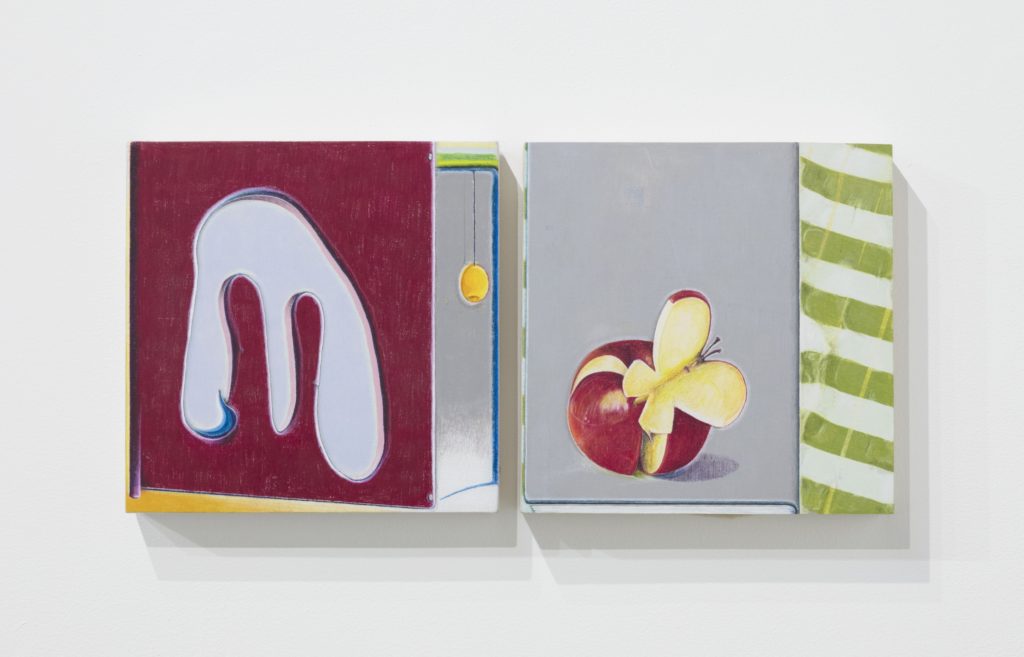

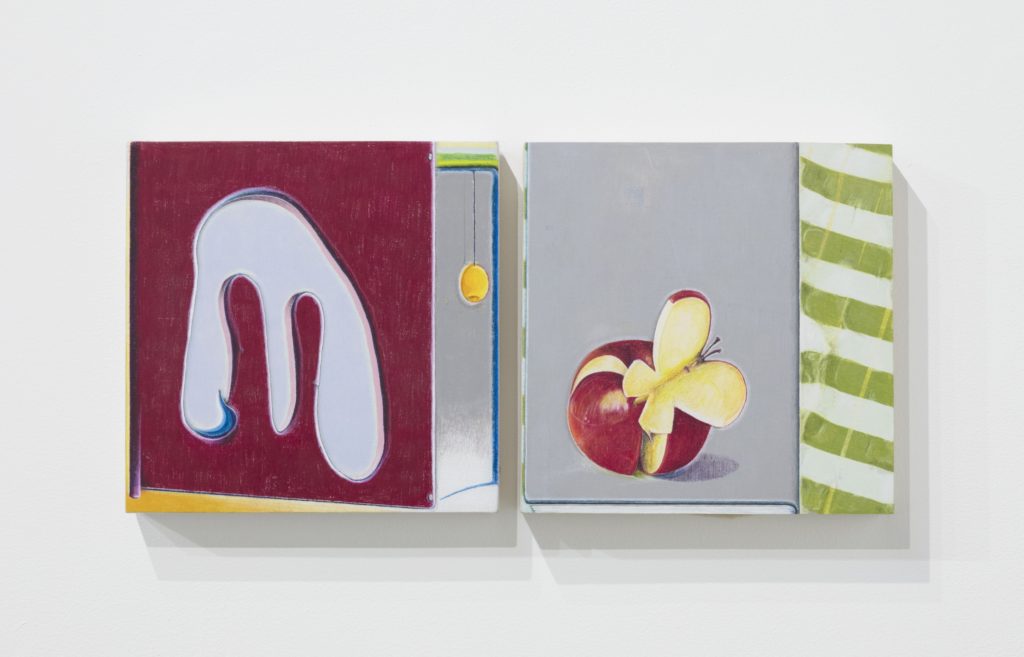

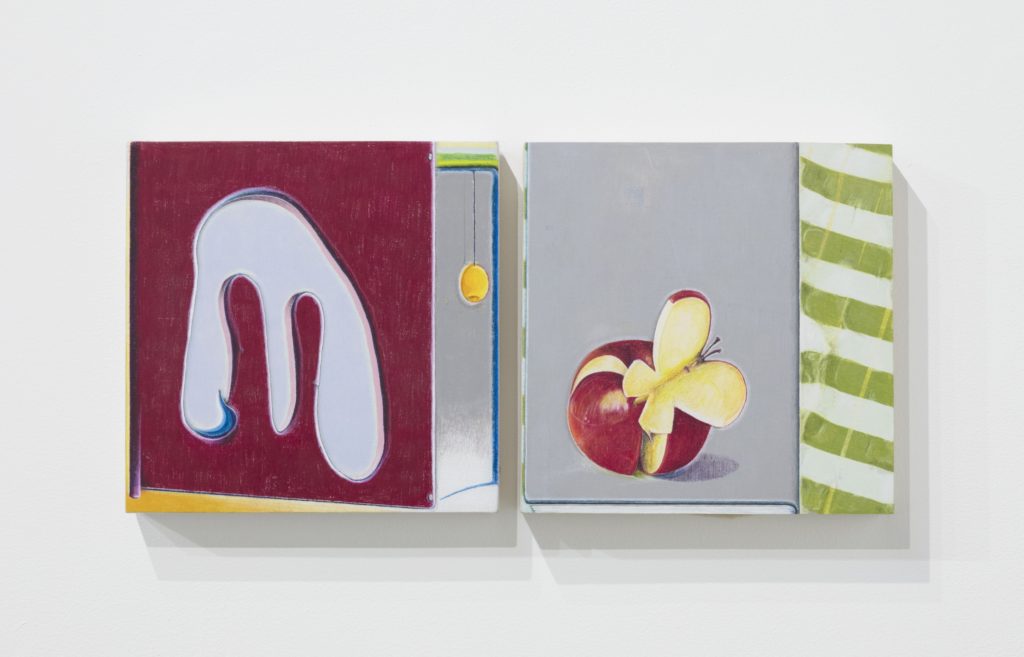

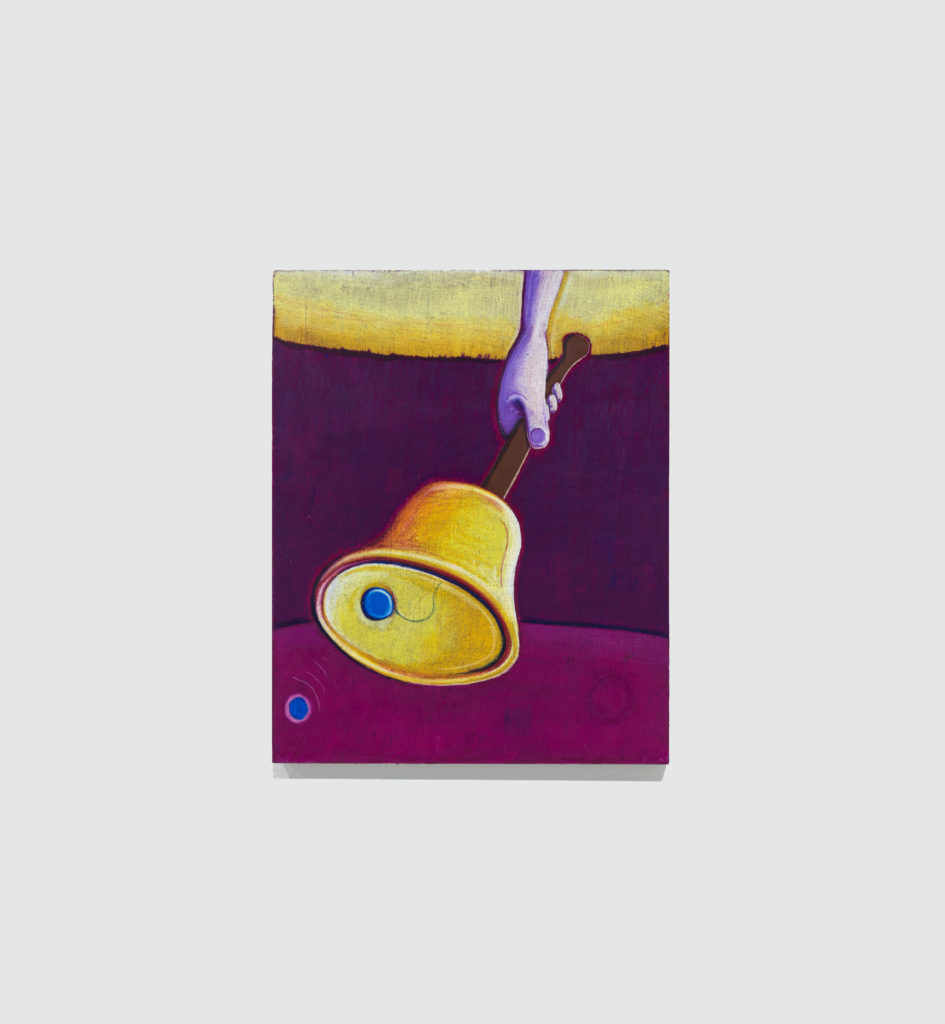

A purple hand clangs an apricot-coloured bell. Three bubblegum-pink earbuds lie tangled atop a blue, yellow and white grid. Thin slices of an apple flutter like a butterfly with a stem in lieu of antennae. The richly saturated abstract drawings in Marlon Kroll’s “sunrise it crystallize” are jocular, yet satisfyingly surreal. There is an insistent sense of play and double entendre at work in Kroll’s solo exhibition at Parisian Laundry. The effect brings to mind inversions, or the feeling of trying to tell a story while a little stoned—pleasant tangents arise and suddenly the story seems to have metamorphosed, perhaps becoming something clearer.

In the exhibition, Kroll presents a multimedia installation alongside a series of vignettes made with coloured pencil on gessoed muslin. The former includes low-resolution photographs printed on 8.5-by-11-inch computer paper; stacks of roughly painted ceramic rings; an embellished LP record cover of Shakespeare Songs and Lute Solos; a projection of flies fluttering GIF-like upon four glass panes smeared with yellow goo; and assemblages of found and augmented objects, such as blinds, ceramic pieces and a pair of men’s black leather dress shoes. Various household objects also populate the gallery, including pats of partially unwrapped butter, fake teeth, a tiny bell and a small lighter with a Canadian flag design, which sits atop the projector.

Kroll’s 18 new drawings continue the trajectory of winking minimalist detail shown in an earlier solo show this year, “Thirsty Things,” at Clint Roenisch. Several “sunrise it crystallize” drawings seem to reference each other, forming pairs like in a memory game. Though the coloured-pencil works are more or less spread evenly across the gallery’s walls, one feels compelled to meander in order to appreciate motifs from different angles. Character Revolution (2019), a vertical triptych of butterfly-like forms, is installed low—the bottom canvas propped against the floor as though temporarily placed in a new studio or apartment. In retrospect, I note that my looping path mimicked one of the assured, sweeping lines in a Kroll drawing. Swollen, aubergine-esque shapes repeat, as do varyingly literal references to butterflies, apples, shoes and human ears. The curves of Kroll’s loose, yet intentional, contours also recall the ceramic rings derived from an earlier phase of his practice.

Marlon Kroll, Olympic Rings / Holding Hands, 2019. Glazed ceramics, coins, bottle caps, glasses with evaporated tums, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist/Parisian Laundry. Photo: Maxime Brouillet.

Marlon Kroll, “sunrise it crystallize” (installation view), 2019. Courtesy the artist/Parisian Laundry. Photo: Maxime Brouillet.

Marlon Kroll, “sunrise it crystallize” (installation view), 2019. Courtesy the artist/Parisian Laundry. Photo: Maxime Brouillet.

There is something deliciously languid about the atmosphere Kroll has created. Mundane household objects—from juice container lids storing foreign change to a radio lying on its side—soften the graphic edges, internal frames and stark colour contrasts of the drawings. One cannot help but associate the projection of flies with the humming “yellow noise” (a sonic tone that purports to relax the listener) coming from the radio. The yellow-streaked glass panes conjure the feeling of a summer’s day run amok, or a deep sigh when weekend guests depart on a Monday morning.

Images that are self-consciously duplicitous can sometimes annoy me. Is it two profiles or a glass of wine? Is the dress white and gold, or black and blue? With “sunrise it crystallize,” Kroll upends my skepticism toward doppelgängers. As Tatum Dooley aptly observes in the exhibition text, Kroll’s drawings often appear at first like oil paintings. Their high-gloss surfaces and quizzical contents—a ghostly row of clear nail polish in Infinity (2019) or the tip of a penis proximal to a crimson circle in Owl (2019)—invite the viewer into shared inquiry and potentially a mutual chuckle. Kroll’s truest trick, then, may be reinvigorating two-dimensional abstraction with a sense of wit and openness.

Marlon Kroll, Mood Room and Butterfly, 2019. Coloured pencil on gessoed muslin over panel, 30.5 x 30.5 cm each. Courtesy the artist/Parisian Laundry. Photo: Maxime Brouillet.

Marlon Kroll, Owl, 2019. Coloured pencil on gessoed muslin over panel, 36.8 x 27.9 cm. Courtesy the artist/Parisian Laundry. Photo: Maxime Brouillet.

Marlon Kroll, “sunrise it crystallize” (installation view), 2019. Courtesy the artist/Parisian Laundry. Photo: Maxime Brouillet.

Marlon Kroll, Hosiery, 2019. Coloured pencil on gessoed muslin over panel, 38.1 x 30.5 cm. Courtesy the artist/Parisian Laundry. Photo: Maxime Brouillet.

Marlon Kroll, Dawn Bell, 2019. Coloured pencil on gessoed muslin over panel, 38.1 x 30.5 cm. Courtesy the artist/Parisian Laundry. Photo: Maxime Brouillet.

Marlon Kroll, Dawn Bell, 2019. Coloured pencil on gessoed muslin over panel, 38.1 x 30.5 cm. Courtesy the artist/Parisian Laundry. Photo: Maxime Brouillet.