From crisis comes good art; this axiom has gained a lot of relevance lately. It’s a difficult line of thinking, though, because it presupposes the necessity for a new visual language, as if to say that crisis requires an art of its own.

Contemporary art often subordinates the past in favour of the future—perhaps it’s a vestige of the avant-garde. The future, pregnant with possibilities for destruction or redemption, is the consecrated realm of experimentation. But situating art in the future can produce a degree of isolation; it confines us to a linear history in which we are perpetually waiting for answers that are out of reach.

Few crises are more established in our collective consciousness than ecological destruction, and plenty of contemporary artworks look to the future to address the topic. Take American painter John Sabraw’s toxic sludge paintings, or Canadian Kelly Jazvac’s plastiglomerate readymades. Both counterbalance future instability with a futurity of form, creating something altogether new—an art to meet the times.

Marina Roy, “Dirty Clouds” (installation view), 2017. Photo: Woojae Kim. Courtesy Will Aballe Art Projects.

Marina Roy, “Dirty Clouds” (installation view), 2017. Photo: Woojae Kim. Courtesy Will Aballe Art Projects.

Marina Roy’s recent solo exhibition “Dirty Clouds,” at Wil Aballe Art Projects in Vancouver, did something different. Instead of looking to the future for a way out of the present, Roy reminded viewers that “the end” is not simply a dimension looming on the horizon, but an important aspect of the past.

The clustered salon hang of 80 paintings that comprised “Dirty Clouds”—a portion of which are on view in “Leaning Out of Windows” at Emily Carr University of Art and Design this week—converses with a history of painting that harks back to the 16th and 17th centuries. What comes to mind in particular is a history of Flemish, Dutch and even Netherlandish paintings of this time, like those by David Teniers the Younger, Egbert van Heemskerck or Bruegel, paintings rich with symbols on the futility of pleasure, the transience of life and the certainty of death.

In “Dirty Clouds” the hand of God emerges from puffy, auspicious clouds in a painting titled spin, one finger extended towards a swirling cosmos. Other paintings on display present archetypes of sex, birth and death. The fecund innards of sliced fruit or a dripping nest of green eggs with faces evoke a sense of emergence, while silhouettes of decaying, limp bodies or burnt deer carcasses signal death’s foreclosure.

Marina Roy, spin, 2017. Oil and acrylic paint on wood panel. Photo: Alex Gibson. Courtesy Will Aballe Art Projects.

Marina Roy, spin, 2017. Oil and acrylic paint on wood panel. Photo: Alex Gibson. Courtesy Will Aballe Art Projects.

Other paintings quote emblems of scientific knowledge, humanist hubris and the beginnings of the Enlightenment; in these, anonymous hands enter from outside of the painterly frame to mix, pour and prod. The painting emblem (arms and tree) depicts two sets of hands firmly grasping the trunk of a tree—a possible symbol of collaborative scientific progress, but one that also suggests humans’ strangulation of nature.

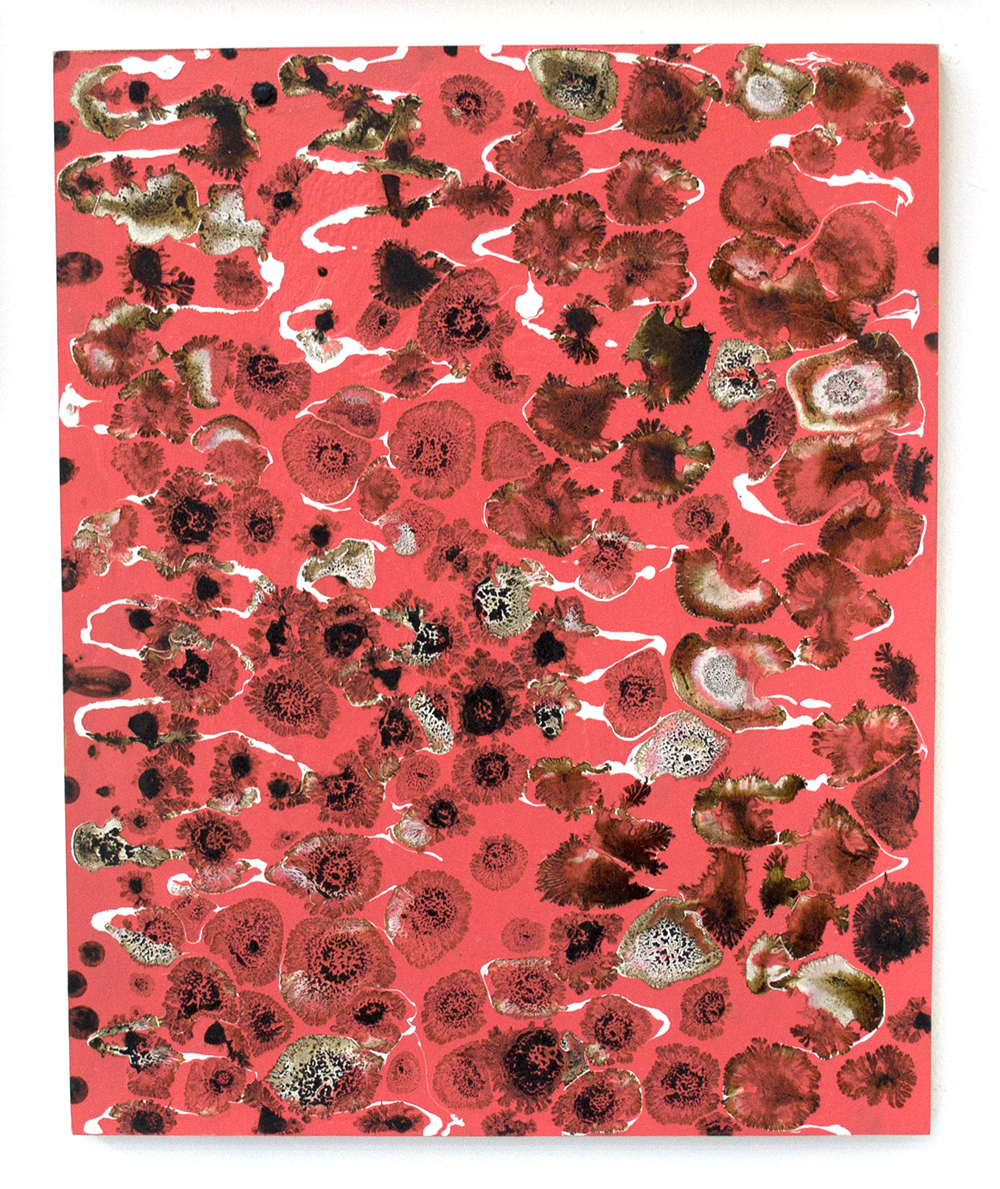

In other works, Roy’s reference to scientific empiricism is less literal and more performative. The panel particles and waves resembles the taxonomic display of a specimen tray. Rather than objects encased in glass, though, it presents a busy composition of red, black and white lichen-like forms branching outward. Some of these forms bleed into one another, and yet the composition retains a sense of arranged order.

These designs result from a chemical reaction that ensues when Roy mixes bitumen with red iron oxide oil paint that she hand-makes by grinding pigments into linseed. She then uses an eyedropper to apply this mixture onto the acrylic-latex paint on panel. The result is an enticing composition of fractal configurations; shiny acrylic surfaces of confectionery pinks and greens are offset by the intermittent smear of bitumen and the dirtiness of tar. In particles and waves, as with other works on display, the push and pull of the beautiful and the grotesque is compelling.

Marina Roy, particles and waves, 2017. Bitumen and acrylic paint on wood panel. Photo: Alex Gibson. Courtesy Will Aballe Art Projects.

Marina Roy, particles and waves, 2017. Bitumen and acrylic paint on wood panel. Photo: Alex Gibson. Courtesy Will Aballe Art Projects.

Part of Roy’s investigative process behind “Dirty Clouds” included a period of discussion and research at Canada’s national particle accelerator centre, TRIUMF. As part of the project “Leaning Out of Windows,” organized by researchers Ingrid Koenig and Randy Lee Cutler, 26 artists were invited to a seminar given by five physicists on the topic of antimatter and assigned a physicist with whom to consult.

This experience is palpable across “Dirty Clouds”—in Roy’s contemplation of antimatter through images of earthworms and stardust, as well as in her representational play with black holes and the concept of the universe as origin.

Roy’s visible material experimentation, equal parts control and automatism, connects with the history of experimentation in science and in painting. Roy doesn’t reference alchemy for its illusionistic similarity to painting—she avoids simplifying the discipline to its mythic search to turn lead into gold. Instead, Roy is referencing alchemy to activate the shared inquisitive traits between painter and alchemist, traits that lead to the transformation of matter into different substances.

Marina Roy. additive (left) and cyclops (right), 2017. Shellac, oil and acrylic paint on wood panel. Photo: Woojae Kim. Courtesy Will Aballe Art Projects.

Marina Roy. additive (left) and cyclops (right), 2017. Shellac, oil and acrylic paint on wood panel. Photo: Woojae Kim. Courtesy Will Aballe Art Projects.

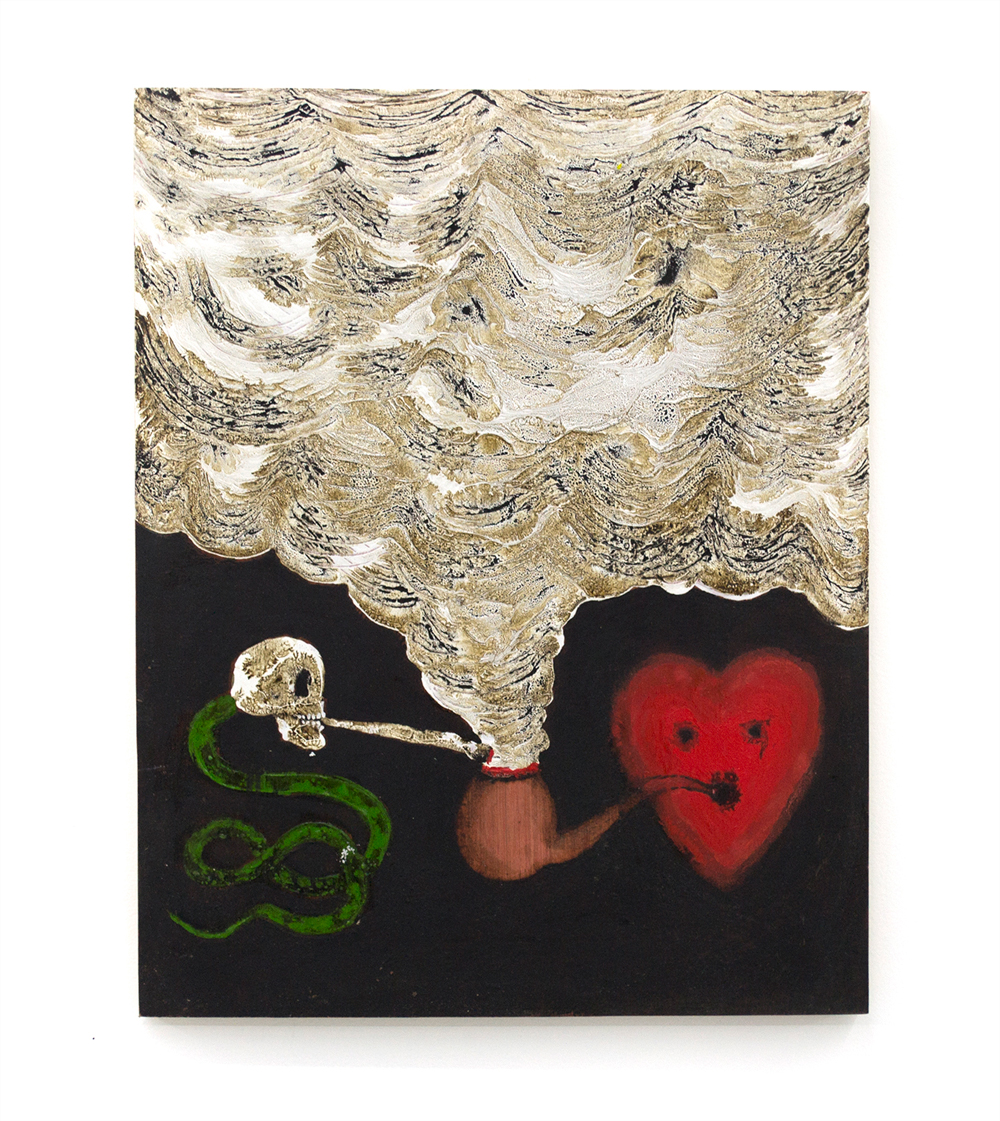

Across Roy’s works, one senses an infinite layering of hands and mediations—not only upon matter, but also upon ideas and images. Rather than seeking an entirely new visual language to articulate the nihilism of our moment, Roy engages with the ways that images of birth and death, beginning and end, have existed throughout painting. In emblem (death drive) a green, coiled snake with a human skull smokes up with a cartoony, wide-eyed love heart—a playful token of life’s ephemeral hedonism.

In order to access the exhibition at Wil Aballe’s art space, one had to pass through Fazakas Gallery, where an impressive display of carving works by Beau Dick and Cole Speck, among others, was on view during the run of Roy’s show. In these carvings, the concept of time exists in tandem with the divine and supernatural. They prove that the traditional can also be exceedingly contemporary, and, when considered alongside “Dirty Clouds,” offered a reminder that an accelerated view toward the future often limits us to a uni-directional framework.

Marina Roy, emblem (death drive), 2017. Oil and acrylic paint on wood panel. Photo: Alex Gibson. Courtesy Will Aballe Art Projects.

Marina Roy, emblem (death drive), 2017. Oil and acrylic paint on wood panel. Photo: Alex Gibson. Courtesy Will Aballe Art Projects.

As a body of work, Marina Roy’s “Dirty Clouds” complicates time, and this is what makes the paintings incredibly generative. This return to history doesn’t necessarily break new ground, nor does it offer a definitively better means of combating crisis than futurity does.

But what “Dirty Clouds” does underscore is that our sense of being “near the end” is as much an inheritance of the past as it is a condition of the future. This is not a pacifying revelation but an impetus to explore how dynamism can be channelled from the language of the past. Roy’s re-examination of this allows her to move beyond self-conscious definitions of the present, and she creates powerfully energetic art in the process.

Paintings from Marina Roy’s “Dirty Clouds” project are on view January 25 to February 8 as part of “Leaning Out of Windows” at Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver.

April Thompson is a writer and curator currently based in Vancouver. Her practice is guided by critical investigation of contemporary art, postmodern geography and spatial politics.

Marina Roy, “Dirty Clouds” (installation view), 2017. Photo: Woojae Kim. Courtesy Will Aballe Art Projects.

Marina Roy, “Dirty Clouds” (installation view), 2017. Photo: Woojae Kim. Courtesy Will Aballe Art Projects.

Marina Roy, “Dirty Clouds” (installation view), 2017. Photo: Woojae Kim. Courtesy Will Aballe Art Projects.

Marina Roy, “Dirty Clouds” (installation view), 2017. Photo: Woojae Kim. Courtesy Will Aballe Art Projects.