The restrained layout of Lorna Bauer’s recent solo exhibition, “Tools for Idlers,” with its concrete cast structures, delicate glass-blown objects and framed photographs, stood in stark contrast to its point of origin: the lush Sítio Roberto Burle Marx in Rio de Janeiro, former home and garden to the late Brazilian landscape architect.

Burle Marx was known to use the natural elements of an ecosystem as his aesthetic guides, delicately corralling but never constraining the sprawling native flora of his home country. While touring the Sítio during a month-long research residency organized by Montreal’s Diagonale Art Centre in 2017, Bauer unearthed the story of Margaret Mee, the British botanist and close companion of Burle Marx. Mee chose to draw rather than photograph her botanical subjects, seeming to illustratively enter the plants themselves, as pointed out in Rebecca Lemire’s accompanying exhibition text.

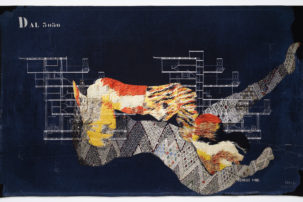

As a counterpoint to the pair’s floral aesthetic, Bauer introduced a third character to her research project: the sleek modernist architect Le Corbusier. The inclusion of two photos from his Unité d’habitation in France seem to pull the gallery’s cement floor up the wall and into the cool grey-blue images themselves, forcing urban space and its distinction from the sunny foliage of the Sítio into focus. At once, an important asymmetry is established, precariously balancing elements of the natural world with the materials used to control it.

Bauer’s exhibition doesn’t uphold Mee’s valorization of drawing nor Le Corbusier’s similar disapproval of photography (the camera is only a “tool for idlers,” he once said). Cheekily, she presents us here with the very thing Le Corbusier denounced: the evidence of her “idling,” through photographs of her time spent in the Sítio. With playful vantage points, layered reflections and subtle nods to the apparatuses of gardening, Bauer’s images form her own space: the house of the artist.

On the gallery floor stands a low concrete table topped with meandering disembodied hands, cloudy sea-green glass ropes and a milky pink orb. To the left, a salt-stained turquoise skin and cluster of glass-blown jugs complete the installation. Crouching, I examine one of the jugs. The glass changes colour depending on thickness, Bauer tells me. The jug’s wide lip is a cloudy teal grey. As the glass balloons, grey gives way to dusty pink, to red, to orange, peaking at a candied clear yellow. The thinnest curves are cradled by a copper mesh. There are many moments like this when encountering Bauer’s work, where austerity gives way to an abundance that emerges in the details. I’m left thinking about abandon, about control, about overgrowth and grooming, about earth and concrete.

Existing between these tensions, Bauer establishes her voice among the characters of her research. Though working from and with the stories of Burle Marx, Mee and Le Corbusier, Bauer’s body of work moves beyond, fermenting their histories to create something entirely new. In that, Bauer announces her own techniques of choice: the eschewal of obvious narrative, the abstraction of the everyday and the cunning use of craft.