What does the physical body of the Internet look like? Currently, there are more than 260 in-service fibre-optic submarine cables embedded in the ocean floor, stretching between continents to transfer online information like an infinitely complex subway system. While satellites broadcast from the heights of our skies, the majority of our inter-continental data travels deep underwater. Yet, for a system of information that seems increasingly nebulous and powerful, the Internet’s undersea nervous system is remarkably vulnerable. Rarely monitored and poorly protected, the physical integrity of these submarine cables is frequently threatened by a variety of foes including anchors, trawling and—perhaps even—sharks.

Jenn E. Norton’s exhibition at the Art Gallery of Hamilton is a playful take on the great heights and the dark depths of our information age. Divided between three separate rooms at the AGH, “Dredging a Wake” imagines the effects—both deeply embodied and increasingly intangible—of today’s accelerated accumulation of data. However, Norton remains deliberately ambiguous about our place within the digital abyss: Are we slowly drowning, or deftly following a current? Falling into a chasm, or ascending to the stars?

The first of three installations accessible to AGH visitors is Precipice (2014); viewers walk into a large room with a shell-like screen coiled in its centre. Walking into the spiral enclosure, visitors are met with a simple wooden chair on a circular platform. Sitting in the chair triggers the motorized platform to rotate slowly, and ambient music swells as viewers are suddenly surrounded by projected video of a swimmer navigating some watery depths riddled with fluttering (are they flying, floating or falling?) sheets of paper, floppy disks, cassette tapes and CDs.

Doline (2014), the second installation in “Dredging a Wake,” also toys with these sink-or-swim trajectories: strange amalgamations of obsolete data containers (CD-ROMs, VCRs, tape decks, filing boxes) rotate on loudly whirring motors. This is set to a haunting soundtrack of voices recounting dreams of falling, sourced from a 1964 BBC program by pioneering electronic musician Delia Derbyshire and playwright Barry Bermange. The AGH describes these twisting monuments as if they were slowly sinking into the gallery floor, yet in my mind, they could just as easily be ascending upwards, spiralling indefinitely into the sky. “Suddenly I’m falling… I’m falling upright,” voices in Derbyshire and Bermange’s soundtrack echo this confusion. “It’s in space… a complete feeling of space and nothingness, nothingness.”

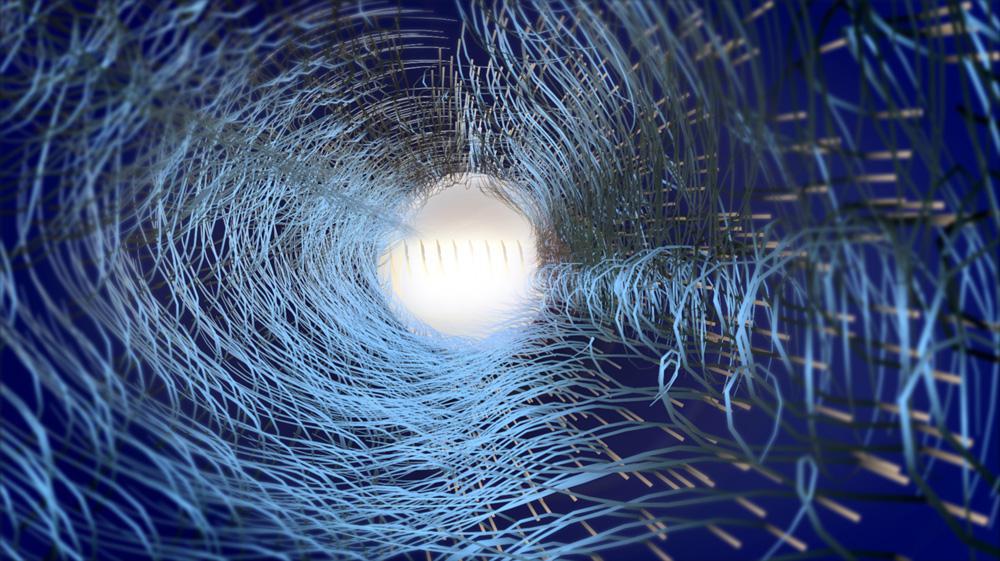

Entering the third installation, Doldrums (2014), viewers are provided with 3-D glasses. Two projections face each other in the darkened room, yet the three-dimensional waves and undulations they generate seem to extend beyond the walls and flood across the floor and viewers’ bodies. As I stood within the Doldrums space, it took me a moment to realize that the projection surfaces are in fact reflective Plexiglas, producing a disorienting effect as the projected light bounces off each reflective “screen” into the gallery space itself.

Featuring a surreal array of oceanic horizon lines, cartoonish light bulbs and full moons in a sequence not unlike something out of 2001: A Space Odyssey, the projected—and mirrored—animations in Doldrums also seem to interact in playful ways with their own sources. Seeing the pinprick of light from the projector itself reflected back onto the projection it has created causes a lovely little slippage of image and apparatus: on the image of an oceanic horizon, the reflected projector light seems to assume the role of the sun, completing its own image.

That being said, the immersion promised in Doldrums is never complete. The reflective room generally remains too dark for viewers to see themselves reflected back; our bodies are rarely made visible in Norton’s digital abyss. And, despite the three-dimensional presentation, some of the computer-generated animations in Doldrums—and throughout “Dredging a Wake”—retain an impenetrably smooth flatness: we are thrown against a static horizon line, not into the swirling depths of an ocean floor.

While the immersive ideas behind “Dredging a Wake” occasionally seem to exceed the limits of what its presentation can offer, Norton tempers the cold smoothness of her dark abyss with a subtle sense of humour and whimsy. The countless, fluttering sheets of paper and the amalgamations of out-of-date office fixtures obliquely recall a few iconic scenes from Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985), and the motorized bases of these sculptural forms hum throughout the installation space like an orchestra of rewinding VCRs. The humble wooden chair (complete with sewn seat cushion) at the centre of Precipice seems more likely sourced from a dusty reference library than the Starship Enterprise.

And so, like the thought of a shark threatening the immensity of the global Internet by snacking on a submarine cable, there is a charming and playful element of technological subterfuge embedded throughout “Dredging a Wake” that supplies the installation with a surprising yet much-needed sense of warmth.

Freud understood “oceanic feelings” as a psychoanalytic sense of limitlessness, a felt connection to the immensity of the external world. Jenn E. Norton’s “Dredging a Wake” plays with a similar sense of boundlessness, imagining the topography of our digital landscape in all its extreme heights and cavernous depths. While the installation occasionally disrupts its own promise of immersion, “Dredging a Wake” is remarkably disorienting and charming all at once.