It seems odd to speak of the horrors of the art world when there are so many more urgent horrors to speak of. “We’re not saving lives here,” one of my former colleagues used to announce to the office on particularly stressful days, her tone sarcastic but also encouraging, as if the thought of us not saving lives would inherently calm us down. When lives have been at stake, and lost, in the art world—Dash Snow, Annie Pootoogook, Jack Goldstein—there is a predictable, revolting shrug. What indeed should the art world have to do with caring for and saving lives, when the romantic myth of art abnegates bodies; relegates suffering only to its relationship with art-making; and, vulture-like, stalks the death (whether premature or mature) of those for whom decline, by, say, old age or mental-health issues, has made living unmarketable?

Jack Goldstein and the CalArts Mafia was a book published by Minneola Press in 2003. Only months before, in March of that year, Goldstein had died of suicide, with enough time for his death to be acknowledged in the book’s introduction by its writer-compiler Richard Hertz. Not enough can be said to recommend Hertz’s haunting, revelatory book, which interpolates transcribed conversations with Goldstein, a Jew from Montreal and an art-world misfit, with transcribed conversations with those who knew him, including John Baldessari, James Welling and Robert Longo. Hertz’s work contains so much truth-telling that it can feel positively seditious, an effect compounded by its subjects speaking through transcription, rather than through the jargon-laden and morally detached “texts” we are used to expect from contemporary-art insiders.

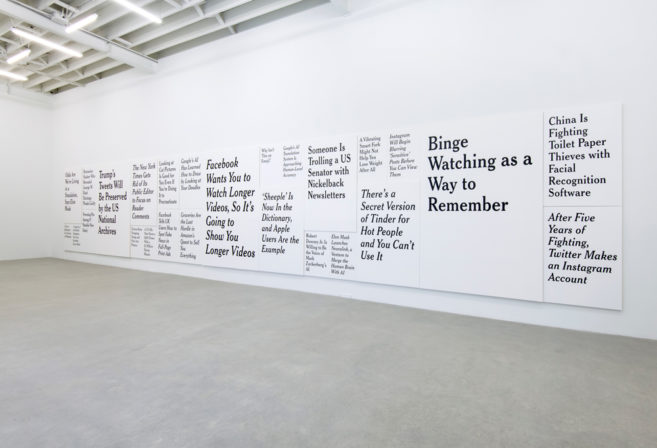

Ron Terada, Jack, 2016–17. Acrylic on canvas, 14 panels, 2.03 x 1.63 m each. Courtesy Art Gallery of Ontario. Purchased with the assistance of Eleanor and Francis Shen, 2017.

Ron Terada, Jack, 2016–17. Acrylic on canvas, 14 panels, 2.03 x 1.63 m each. Courtesy Art Gallery of Ontario. Purchased with the assistance of Eleanor and Francis Shen, 2017.

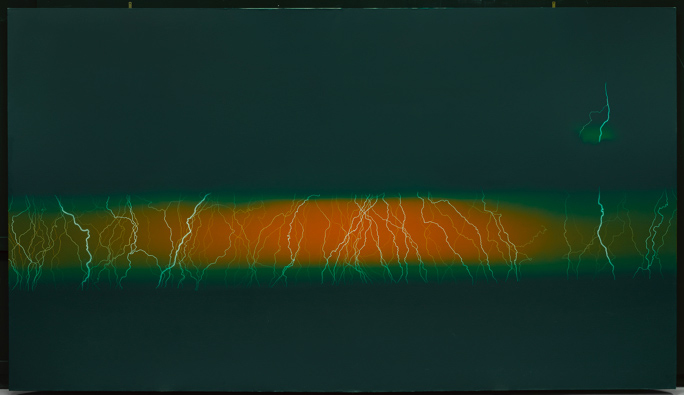

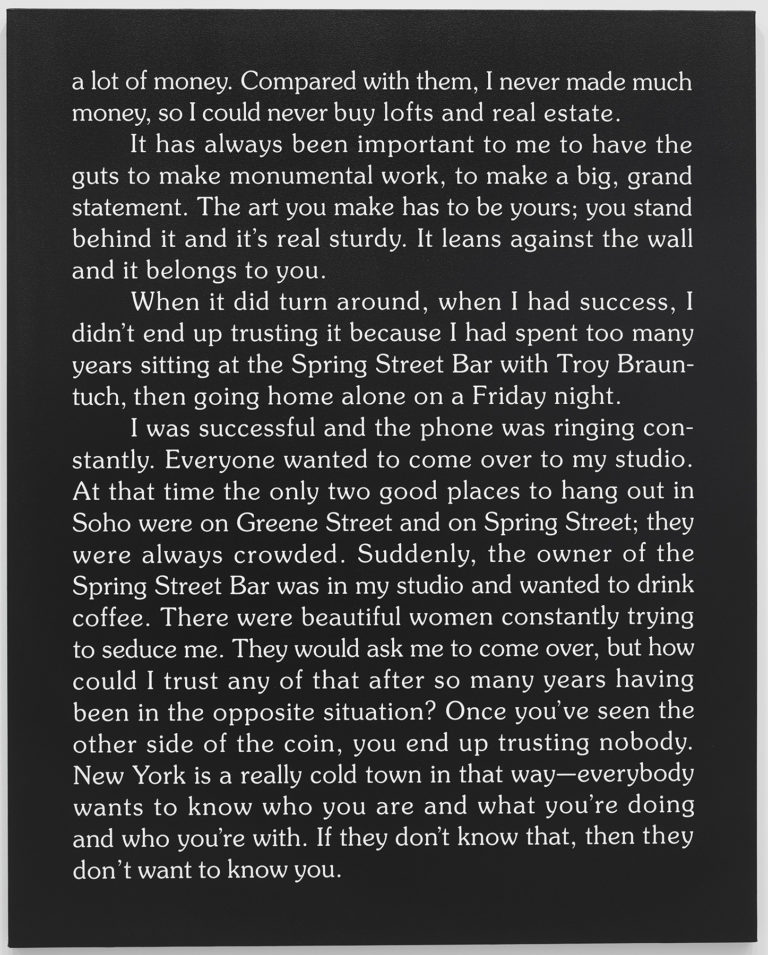

Since 2011, Ron Terada’s Jack paintings have been excerpting various passages from this book, all Goldstein’s words, on uniformly sized canvases, with white type on black backgrounds. In “Jack and the Jack Paintings” at the Art Gallery of Ontario, curator Kitty Scott brings a suite of Terada’s works, readable across canvases (more or less forming a chapter from Hertz’s book), in contact with a large-format 1983 lightning painting of Goldstein’s from the AGO’s collection, made at the height of Goldstein’s New York fame. As you circle around Terada’s paintings, you pass Goldstein’s monumental work, and eventually read about Josh Baer of White Columns and his scapegoating of Goldstein to an angry client, who wanted one of Goldstein’s lightning paintings but was deprived of it because of Baer’s wish to appease wealthier clients. At this point in the installation, the AGO’s own lightning painting hangs behind you; it seems to emit a crackle of doom.

“It’s a microcosm of Hollywood. The artworld is all about money and deals,” says Goldstein to Hertz, readable on one of Terada’s canvases. “People don’t mean anything along the way.” If the Jack paintings make an aspect of Goldstein visible—make into material the very thing (i.e., not playing nice) the art world thought devalued Goldstein’s own material output—they are equally about invisibility. Goldstein disappeared at the end of his life; when he began to withdraw years earlier, due to introversion, burnout, blow-ups, break-ups, insecurity, drug use and depression, the art world, according to Hertz, saw this as an affront rather than a concern. For his thesis project at CalArts, Goldstein buried himself alive. Predictably, Goldstein was shown at the Whitney Biennial only a year after his death; Terada’s clever and perversely appropriative paintings are, among other things, the more appropriate exhumation.