Art is a gendered practice. Mediums like wood or metal are traditionally associated with men, while more fragile materials like textiles or ceramics are often associated with women. This tendency is especially evident in the acquisition practices of collecting institutions: greater value is bestowed on painting and sculpture than on objects deemed “mere craft.” Over time, this value framework has led to gender imbalances and stark omissions in the collections of many major art institutions.

The division of genre, and consequently of gender, is addressed in “Her Metal,” a group exhibition at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery, curated by John Leroux. As a premise, Leroux commissioned six metalsmiths—all women—from the New Brunswick College of Craft and Design’s jewellery and metal arts faculty to respond to historical works of their choosing from the gallery’s permanent collection.

The new works produced by Brigitte Clavette, Kristyn Cooper, Kristen Bishop, Kristianne Levesque, Audrée H. St-Amour and Erica Stanley were displayed alongside the selected collection pieces. Each piece activated its static predecessor, the majority of which were paintings and drawings by prominent male artists. The women responded in different ways—some focused on the symbolism in the older work while others produced objects that exposed unseen narratives within the original compositions.

Mary Pratt’s still-life painting Kareila Couch (1978), a close-up of a vibrant orange sofa, became a starting point for Krystin Cooper. Using sterling silver, Cooper carefully crafted Orange Curio Capsule (2018) to hold and display items she imagined could be found within the sofa’s depths, among them a screw, a key and a coin. Domestic duties monopolized the early years of Pratt’s career and informed her practice. She eventually became known for highlighting deeper meaning within the ordinary and underrecognized elements of traditionally female experiences. It is therefore fitting that Cooper secured a place for these hidden objects, demonstrating that they—and what they represent—are worthy of value and care.

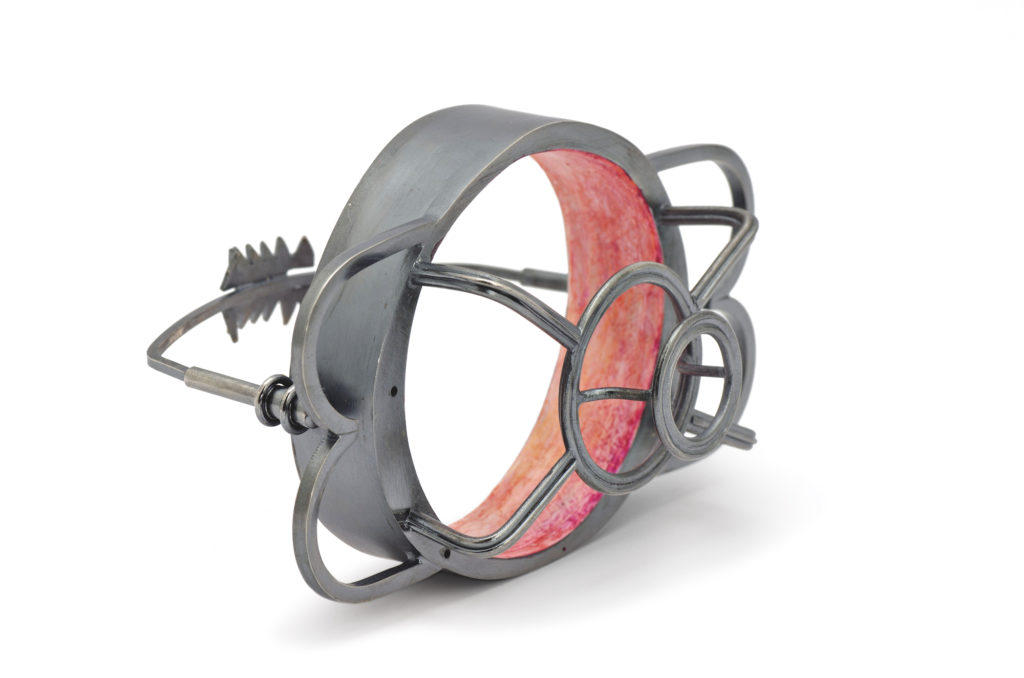

Audrée H. St-Amour responded to Acadian artist Yvon Gallant’s Balloon Buster (1977), which shows a spattering of deflated balloons on a nondescript surface. According to St-Amour, “Balloon Buster can be translated freely from the Québec slang expression ‘péter la balloune’ which refers to bringing someone back to reality” from a euphoric state. St-Amour has cleverly created a sculpture from sterling silver whose appearance falls somewhere between futuristic kitchen tool and medieval torture device. A balloon can inflate inside the metal chamber until it meets a set of sharp teeth, and its imminent destruction—here St-Amour expands and bursts the painting’s narrative beyond representation and into reality. The work of these artists stands out in their conceptual and material explorations. They are expertly rendered and complexly contemporary. Even with works by historical male figures looming large next to them, the new pieces in this exhibition forge a position for their makers in the New Brunswick art canon that’s as strong and valuable as the metals they shape.

Kristyn Cooper, Orange Curio Capsule, 2018. Sterling silver, copper enamel, lapis lazuli, flocked found objects. Courtesy Beaverbrook Art Gallery. Photo: Drew Gilbert.

Kristen Bishop, Inspirit, 2018. Steel sheet, 23Kt gold leaf, ink, acrylic paint, copper screen. Courtesy Beaverbrook Art Gallery. Photo: Drew Gilbert.

Brigitte Clavette, Clavette after Freud after Chardin, 2018. Sterling silver, steel, paper, wood. Courtesy Beaverbrook Art Gallery. Photo: Drew Gilbert.

Kristianne Levesque, I Am, 2018. Sterling silver, copper, brass, agate. Courtesy Beaverbrook Art Gallery. Photo: Drew Gilbert.

Erica Stanley, Echo Echo Echo, 2018. Copper, enamel paint. Courtesy Beaverbrook Art Gallery. Photo: Drew Gilbert.

Audrée H. St-Amour, Balloon Buster, 2018. Sterling silver, paint. Courtesy Beaverbrook Art Gallery. Photo: Drew Gilbert.

Audrée H. St-Amour, Balloon Buster, 2018. Sterling silver, paint. Courtesy Beaverbrook Art Gallery. Photo: Drew Gilbert.