In a thoughtful collection of work displayed together in “trade-treaty-territory,” artist Hannah Claus, of English and Kanien’kehà:ka/Mohawk ancestry, continued to explore the complexities of ongoing trade and treaty relationships. Through video, sculpture and two-dimensional pieces, she intertwines the roles of ceremony, mapping, memory and differing worldviews.

A video of sunlight shimmering and dancing on deep blue water was projected against a back wall, providing a mesmerizing backdrop for the exhibition. As the water gradually grew darker, glints of sunlight began to look more like stars in the night sky. all this was once covered in water (2017) captured ongoing natural cycles of the earth, throwing us back to a time before the imposition of borders and land titles.

Just to the right of this watery scene was the route that ocicâhk preferred (2017), a series of 10 works on paper based on a charcoal-and-birchbark map (originally drawn by a Cree guide in the 1750s) depicting a trade route linking Lake Winnipeg and Lake Superior. A delicate laser etching of the route is layered with various repeated and rotated details from the original map, and coloured with tea. Claus used a Japanese hole-punch to render the Pleiades constellation in copper leaf overtop of these geographical components, tying this example of Indigenous map-making to a journey underneath the stars. Each print, varyingly mottled from the tea-colouring process, exists as a different record of the same action; together, they are subtly dynamic, and reflect a world transformed since the arrival of European settlers.

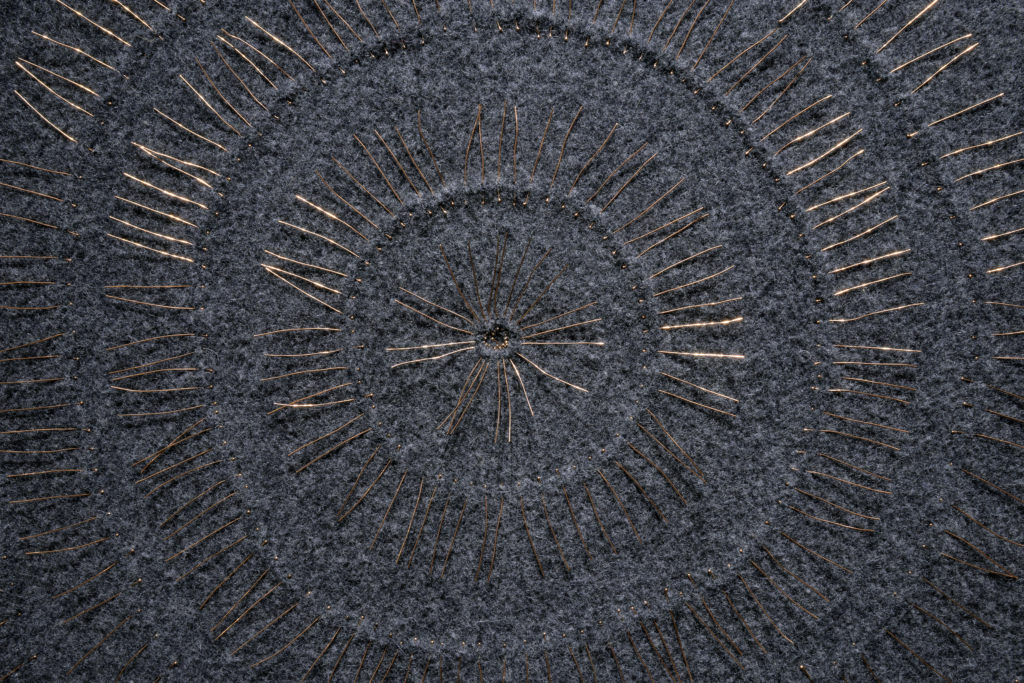

Claus describes copper, a conductive and light-catching material, as the heartblood of the earth. The metal appears again in trade is ceremony (2019), a series of four large, grey woolen blankets. Here, irregular, thick, needle-like headpins are pinned in bands and rows that form geometric patterns based on wampum belt symbols. Each piece carries its own pattern and reflected subtitle: (council), (pine), (sun) and (fire), connecting Indigenous ceremonial practices and symbols. On the opposing wall hung three bright-red blankets, a stark contrast to the muted colour palette of the rest of the space. Here, instead of copper pins, Claus uses silver-plated steel ones to repeat a single pattern on each piece: one group of pins surrounded by another—a closed and encroaching group intent on imposition, self-serving and self-protecting. Silver too is a conductive material, but lacks the warmth of copper. This series is simply titled, invaders (2019). As a settler Canadian with Irish and Scottish heritage, I see myself and my lineage in these silver pins, reframed and renamed, in language that more accurately captures the violence and intention of the colonial agenda.

In the middle of the gallery stood five vitrines, each containing a single beeswax-cast teacup encircled by cedar leaves, rendered from the same deep yellow wax. The cups in this studies (2019) series are based on Claus’s mother’s inherited mismatched collection, here uniquely deformed, semi-melted from having boiling water poured in to them, as if the cedar tea, used in ceremonies and likely offered to some of the first settlers, had actually been served in these delicate wax vessels. The cups act as evidence of spillage and small-scale disaster of which we see only the remains, and point to fractured trust and broken agreements; deformed and unbalanced colonial results, stemming from a once-in-good-faith meeting over shared tea.

Claus poetically asks us to contemplate our existence on this land, and in relation to one another. As tuned in as I would like to think I am, there are gaps inherent in my settler worldview as I embody a privileged place in this country. Claus’s work reveals how far this type of long-term and wholistic engagement is from my own daily existence and thought patterns. Addressing these gaps feels urgent in light of the violent RCMP raids in Wet’suwet’en territory and the solidarity actions that spread quickly throughout the country. As settlers, this means seriously re-examining our roles and responsibilities, holding ourselves and others accountable—deep into the past, and far into the future, taking action toward long-lasting change and meaningful cultural shifts.

Installation view of Hannah Claus, “trade – treaty – territory,” Dunlop Art Gallery, 2020.

Hannah Claus, invaders, 2019. Silver plated steel pins, wool blankets.

Hannah Claus, invaders (detail), 2019. Silver plated steel pins, wool blankets.

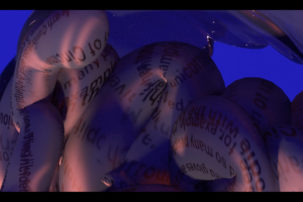

Hannah Claus, fancy dance shawl for Sky Woman (detail), 2019. Mixed media.

Hannah Claus, fancy dance shawl for Sky Woman, 2019. Mixed media.

Hannah Claus, the route that ocicâhk preferred, 2017. Print.

Hannah Claus, the route that ocicâhk preferred, 2017. Prints.

Installation view of Hannah Claus, “trade – treaty – territory,” Dunlop Art Gallery, 2020.

Hannah Claus, studies, 2019. Beeswax.

Hannah Claus, trade is ceremony (detail), 2019. Copper pins, wool blankets.

Hannah Claus, trade is ceremony (detail), 2019. Copper pins, wool blankets.