The painter Georgia O’Keeffe was born in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, and she spent the rest of her life looking for a place that could live up to that name.

The results of this search are broadly known. She found “land like ocean” in the Southwest: first in Texas in 1916, and then later, and more lastingly, in New Mexico. O’Keeffe herself, though, would prefer that audiences overlook these particulars of biography and focus, instead, on the products—her paintings. “Where I was born and where and how I have lived is unimportant,” she declared. “It is what I have done with where I have been that should be of interest.”

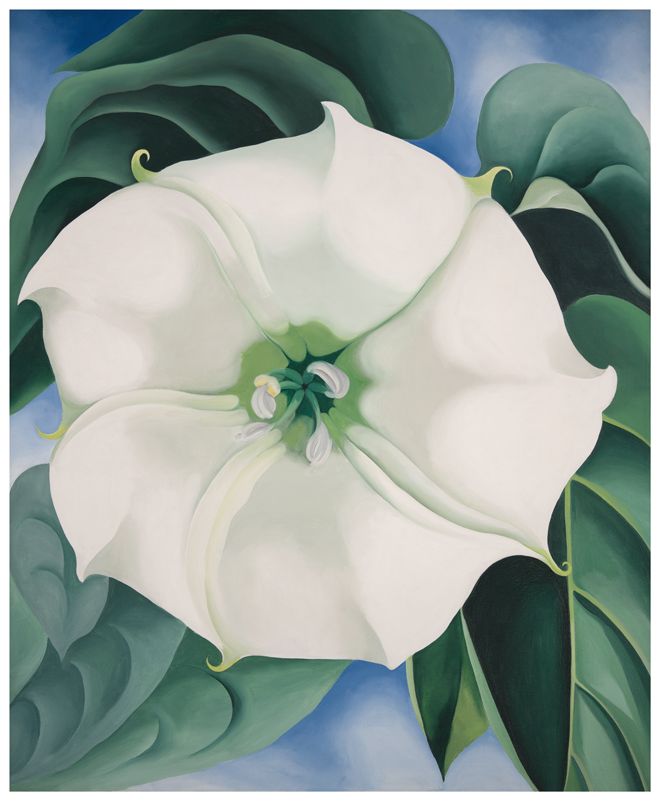

This demurral registers curiously given the exactitude with which O’Keeffe tended to the particulars, a precision made apparent in a recently opened solo exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto. It captures the extremes that O’Keeffe excelled at. She really was best at the very small or the very large—flowers blown up enough to be almost unrecognizable, or the sheer vastness of the land that spoke to her. The infamous floral works, though present, do not dominate. You’re just as likely to find brittle still lifes of mule’s skulls and landscapes of rolling hills. Throughout, photographs of O’Keeffe, largely taken by her photographer husband (and ardent promoter) Alfred Stieglitz, and other friends, including Ansel Adams, supplement her own work.

The Toronto installation of the exhibition, which was led at the AGO by Georgiana Uhlyarik and curated by Tanya Barson and Hannah Johnston of Tate Modern, begins chronologically, with some 1919 abstract charcoal drawings, which are similar to drawings by O’Keeffe that her friend Anita Pollitzer, a photographer and suffragette, pluckily brought in to Stieglitz at his avant-garde New York gallery, 291. He was impressed. He thought that she was the first truly American artist, and perhaps he was right. She knew what she wanted and didn’t stop until she realized it, and few attitudes feel more American than that.

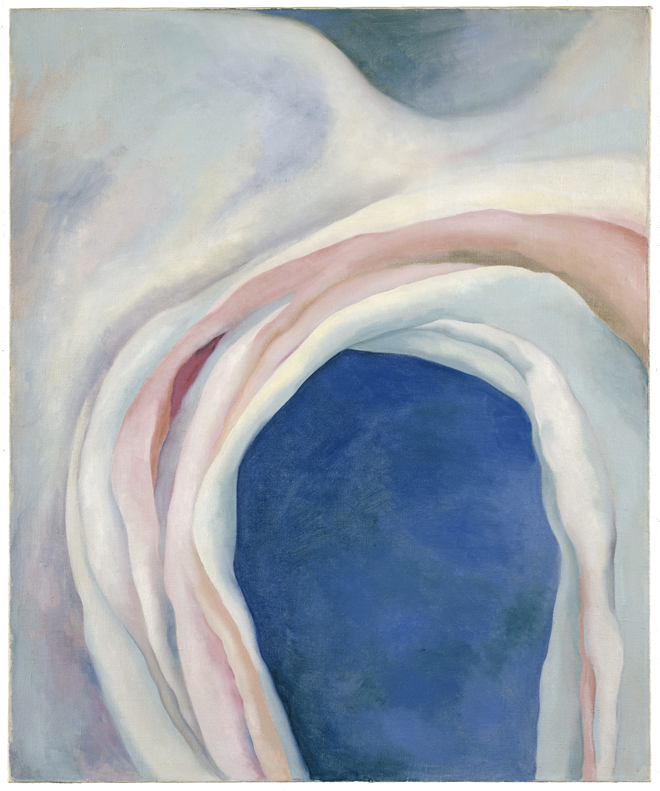

Georgia O’Keeffe, Music – Pink and Blue No. I, 1918. Oil paint on canvas. Collection of Barney A. Ebsworth, partial and promised gift to Seattle Art Museum. © Barney A. Ebsworth.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Music – Pink and Blue No. I, 1918. Oil paint on canvas. Collection of Barney A. Ebsworth, partial and promised gift to Seattle Art Museum. © Barney A. Ebsworth.

Her vision, though not static, was markedly consistent. Her earliest mature works, watercolours and oil paintings, bear the hallmarks that would come to define her: the shades of rose quartz and azure that dominate her palette, rippling fluid shapes that look like music. Yet she took detours. After a torrid correspondence with Stieglitz, O’Keeffe moved to New York City in 1918, partly at his behest, and began painting skylines. There are a handful of these cityscapes on view in the exhibition, and they make for notable but unsatisfying viewing. There’s a reason O’Keeffe isn’t associated with paintings of New York. She renders grey, dull buildings in a comically phallic fashion—a reading that O’Keeffe, ever contrary, would undoubtedly dismiss.

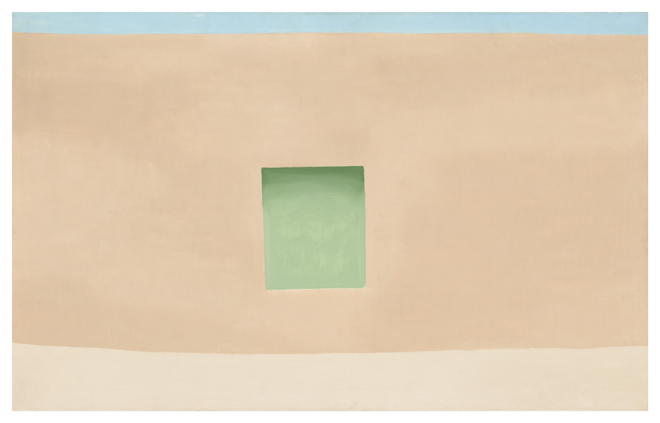

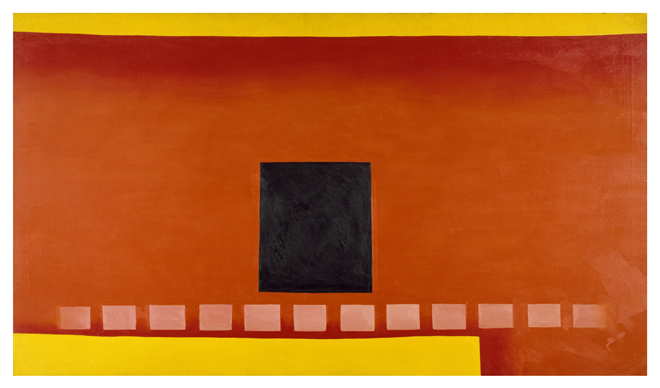

Then there are four paintings, made between 1948 and 1954, that depict one of the artist’s favourite subjects: her beloved patio door on her property in Abiquiú. “I bought that place because it had that door in the patio,” she said. “I’m always trying to paint that door—I never quite get it. It’s a curse—the way I feel about the door.” Each painting strips away a little more, peeling back details of the structure, illustrating its transcendental quality. O’Keeffe does this with many things: the tawny mesas outside of her homes, the adobe buildings dotted around New Mexico. She finds her subject matter, and she returns, and returns, and returns. Every time improving.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Wall with Green Door, 1953. Oil paint on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Gift of the Woodward Foundation), 2015.19.155. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Wall with Green Door, 1953. Oil paint on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Gift of the Woodward Foundation), 2015.19.155. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum.

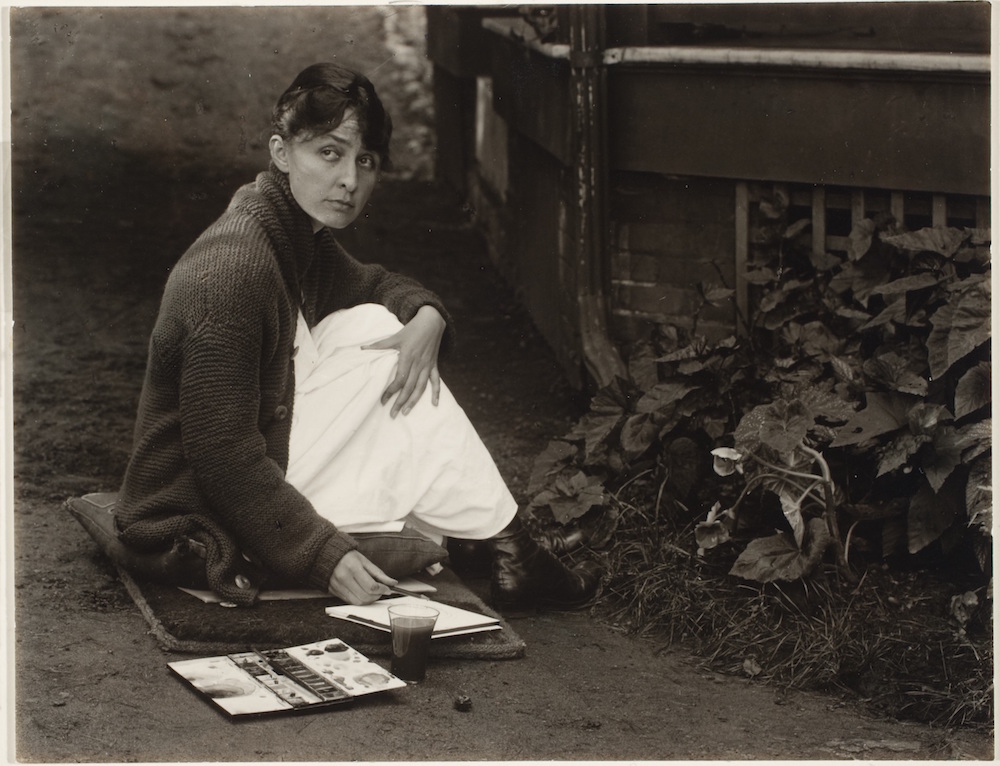

Her inner vision becomes apparent through more than her work—it’s there in the dozen photographic portraits of O’Keeffe taken by Stieglitz that are installed in a smaller gallery, offering visitors a tiny portion of the some 350 images he took of her. In one, he captures her posed languidly in front of one of her paintings, arms raised. Another crops in closely on her face, which is poised atop articulated fingers that seem more like spider’s legs than digits. She stands erect in front of a wooden building in another image, with a black swirl of fabric for a dress, a dark shadow cast behind her. In almost all of them, she appears alone, unrivalled and serious. She is tailored, handsome and entirely beyond reach—a Great Artist.

“I’m glad he wasn’t my boyfriend,” said a woman in the gallery after hearing that O’Keeffe had to pose for hours and follow direction to help Stieglitz create the images he had in mind. And while there are plenty of reasons to relish not being in a relationship with Stieglitz (his reputed egomania and infidelities come to mind), it’s hard to see how these pictures could possibly be one. O’Keeffe becomes otherworldly, a god through his lens. Stieglitz mounts an undeniably objectifying project, and yet I never doubted O’Keeffe’s agency—perhaps because her self-possession appears unshakeable.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1, 1932. Oil on canvas. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Photo: Edward C. Robison III.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1, 1932. Oil on canvas. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Photo: Edward C. Robison III.

O’Keeffe was committed to building a life that looked like a painting, a persona that could be easily and mesmerizingly captured in a photograph. The AGO displays digitized spreads of magazine shoots featuring O’Keeffe and her home, including a famed 1968 cover of Life magazine that propelled her into the public imagination as a rugged, intrepid artist living in isolation on the desert plains.

Another, more thoroughgoing, look at the objects that populated O’Keeffe’s world is currently on view at the Brooklyn Museum in “Living Modern,” which displays her Neiman Marcus wrap dresses alongside her Ferragamo flats and her Alexander Calder brooch. If O’Keeffe were alive today she might think of all of this as her brand. It certainly has commodity appeal: the arid New Mexican vegetation translates nicely into a potted neon cacti in the gift shop; the Frank Restaurant offers an O’Keeffe prix fixe menu peppered with nasturtium oil, fennel fronds and elderflower vinaigrette. (The latter, though admittedly silly, does connect to O’Keeffe’s progressive epicurean leanings. “Whole wheat flour was always ground fresh with the artist’s personal mill. Yogurt was homemade, often from the milk of local goats. Fresh herbs, fruits and vegetables came from the artist’s garden.”)

Georgia O’Keeffe, Black Door with Red, 1954. Oil paint on canvas. Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA, Bequest of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. 89.63. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Black Door with Red, 1954. Oil paint on canvas. Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA, Bequest of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. 89.63. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum.

But dismissing the portraits that O’Keeffe posed for, or the careful attention she paid to her wardrobe, or her dedication to getting just the right Herman Miller chair in her house as frivolous misses the point entirely. O’Keeffe could create a world just as well as she could capture one. But beyond proffering evidence of an unerring aesthetic vision, this underscores something more rudimentary: beautiful, dogged work. A commitment that may have arose intuitively, but certainly didn’t emerge fully formed. All of her aesthetic successes were the result of single-minded dedication to perfecting, reworking, finding the best possible option. She is the consummate Modernist.

The AGO showing, particularly when considered alongside “Living Modern,” makes this clear. All of O’Keeffe’s choices were in service of something larger: artistic success during a time when that, for a woman, often meant disavowing all the trappings of convention. A 1989 biography of O’Keeffe, notes Haley Mlotek in a review of the Brooklyn show, cites the artist declaring to her classmates, “I am going to live a different life from the rest of you girls. I am going to give up everything for my art.”

I think of a moment in Susan Sontag’s interview with Jonathan Cott for Rolling Stone, recently published as a book:

“I don’t want to return to my origins. I think my origins are just a starting point. My sense of things is that I’ve come very far. And it’s the distance I have traveled from my origins that pleases me,” says Sontag. “I’ve spent my whole life getting away.”

When O’Keeffe insists that the public focus on her work, instead of where she lived, or on her paintings, instead of her life choices—despite the unparalleled effort she had put into those choices—it’s the plea of the self-made woman. O’Keeffe spent her life giving everything up and getting away. Perhaps that’s why the desert spoke to her. It’s negation transformed into land.

Seen another way, an empty horizon line looks like a minus sign.

Caoimhe Morgan-Feir is the associate editor of Canadian Art. She is on Twitter @CMorganFeir.

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe with watercolor paint box, 1918. Gelatin silver print on paper. George Eastman Museum, purchase and gift of Georgia O'Keeffe, 1974.0052.0045. Courtesy George Eastman Museum.

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe with watercolor paint box, 1918. Gelatin silver print on paper. George Eastman Museum, purchase and gift of Georgia O'Keeffe, 1974.0052.0045. Courtesy George Eastman Museum.