A memory of the future connotes incongruity: recalling something that hasn’t yet occurred, a psychic forecasting, or a projection onto reality. Can memory’s material vestiges become vessels for time travel? Can their encounters be a way of communing with different temporalities? The works of Diyan Achjadi and Cindy Mochizuki within the Roedde House Museum—a restored Victorian house in Vancouver’s West End built by the Roedde bookbinding family in 1893—suggest that they can.

Achjadi’s and Mochizuki’s “Memories of the Future III” is the third in a project series curated by Katherine Dennis that invites artists to uncover hidden narratives within historic house museums. (Previous iterations, co-curated by Noa Bronstein, include the Campbell House Museum and Gibson House Museum in Toronto.) Responding to the museum’s print histories, from publishing activities to the decorative arts of its period rooms, Achjadi and Mochizuki layer parallel cultural histories within the space, disrupting the dominant European middle-class settler story it has preserved. Their interventions raise questions around whose histories are told, who has agency to speak, and the ways in which memories are transmitted—materially, somatically and intergenerationally along maternal lines—when aspects of memory remain fragmented and silent.

Entering the Roedde House Museum, one is immediately transported to a scene of early 20th century privileged domesticity: glossy wood banisters, lace and velvet curtains, jacquard chaises and curio cabinets. Mochizuki’s film installation Sue Sada Was Here (2018) inhabits the octagonal parlour room traditionally used for entertaining, the projection screen doubling its window as a view into speculative other worlds. The film is a choreographic interpretation of the writings of Muriel Kitawgawa (1912–74), a Nisei or second-generation Japanese Canadian writer active in speaking out against the discrimination towards her community, and the Canadian government’s unjust internment of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War. Beautifully shot, it follows a Japanese girl meandering through the house’s rooms, discovering other Japanese Canadian women—perhaps ghosts—embodying the spirit of Sue Sada, one of Kitagawa’s pen names. In period dress, they utilize books as intermediaries to convey how stories accumulate, are forgotten, or revised. Spoken fragments of Kitagawa’s letters to her brother Wes, who was in Toronto during the internment, are buried by a crescendo of tapping typewriter keys, disheveling of papers and a mysterious piano score—all alluding to the difficulty in accessing stories that have been submerged. The most powerful scene ends in the parlour room itself, when the women, ranging in age from 20 to 85, form an intergenerational chain, books strewn around them and interspersed between their bodies as though transferring somatic secrets. And then a voice: “Time heals the details, but time cannot heal the fundamental wrong. My children will not remember the first violence of feeling, the intense bitterness I felt, but they know that a house was lost through injustice.”

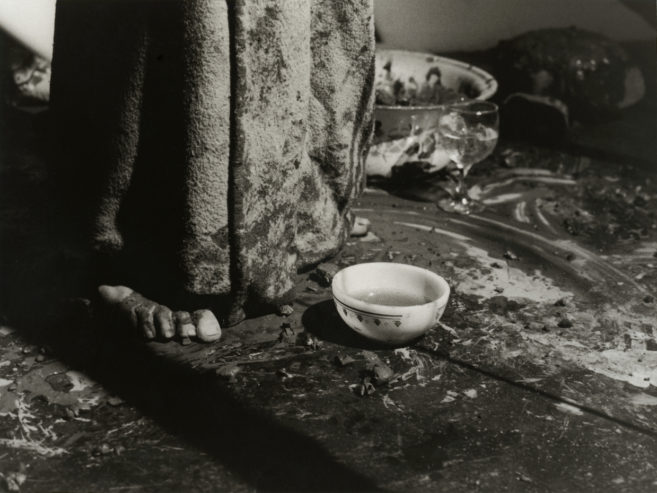

Achjadi’s alterations, subtly interspersed throughout the house, reveal charged histories within seemingly benign decor. Segments of wallpaper are overlayered with Java Toile (Roedde House Redux) (2018), prints which mimic 18th century French toile patterns and chinoiserie, with Achjadi’s added illustrations exposing their colonial roots. Beside the dining room’s porcelain displays emerges the image of a woman wearing an elephant headdress sitting on a tiger, spectral beneath the shadowed vine pattern that creates a double-vision. (This was inspired by a ceramic candelabra Achjadi found at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, where such female figures signified “continents.”) In other rooms, the Java Toile imagery further subverts misrepresentations of an exotic “East” through haunting exaggerations: hybrid human-animal spirits, deceased (hunted) rhinoceroses and disconnected Javanese landscapes interplay with the museum’s displays of taxidermied animals, ivory combs and headless dressed mannequins, suggestive of the casualties and misunderstandings implicit in collecting cultures. Meanwhile, handkerchiefs unassumingly draped in the upstairs bedrooms host other cross-cultural contaminations, and require careful looking: in the Home Invasion series (1998–9), Achjadi embroidered images of guns and soldiers upon family heirlooms from her English Canadian grandmother, contrasting delicate materials with looming brutality to materialize how colonial and militarized violence infiltrates the domestic. Untitled (handkerchiefs) (1998–9) bear faded, silkscreened images of Achjadi’s Indonesian grandmother, Adimah, who died of an asthma attack during the 1949 Indondesian War of Independence, unable to receive medical care due to the Dutch colonial government’s imposed curfew. The intimacy of cloth-to-body (covering the mouth), and the vine-like suffocation of camouflage embroidered over Adimah’s portrait, conflate within Achjadi’s desire to link the unspoken inequality of fates across her family histories.

Memories that cannot be articulated will find other ways to emerge. By inserting histories otherwise absent into the Roedde House, Achjadi and Mochizuki access memory’s haptic and corporeal power, shifting viewers’ associative experience of the space, and re-inscribing different memories and presence to be carried forward. The entanglements of diverse cultural narratives, while not without trauma, underlie their need to intersect in conversation, rather than the geographic separation typical of museums, in order to decolonize these spaces and invite integrative understanding, even healing. From there, we can begin to envision different, possible futures.