If dance-on-film is a recent fixation of contemporary art, the connection is hardly new. Indeed, dancers appeared in some of the earliest films. Performer Annabelle Whitford was in an 1895 Edison Co. kinetoscope, facing the camera and waving a billowy dress back and forth in a “serpentine dance.” Archive.org, which hosts a version of this film, tells us it was banned because viewers had a glimpse of Whitford’s underwear. The website also quotes critic Charles Champlin’s contention that the real sensation was the medium of film itself—“the instant and immense popularity of the movies that stirred the first fears of their corrupting and inciting power.”

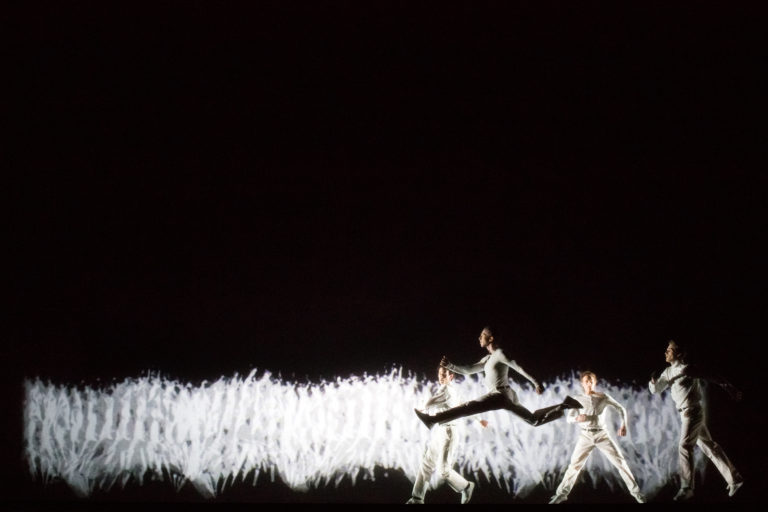

For Scottish-Canadian filmmaker Norman McLaren, who is the subject of the National Ballet of Canada’s new production Frame by Frame, this was deeply true. Also deeply true for him: if dancers appeared in early film, and consistently onwards, it was not just because their beautiful moving bodies were the ideal object for the mesmerism of the developed and projected image, but because the medium itself, a trick of the eye combining 24-frames-a-second into a flickering simulation of life, also moves. Technology is a body. When it records another body—or rather, when it records it well—alchemy happens. In the opening scene of Frame by Frame, a figure of McLaren moves across the stage slowly, dressed in white and bathed in black-and-white projections of his form. The scene moves in so many ways, is such a celebration of how gorgeous life and art can be when they move in tandem, that it moved me to tears. So often in Frame by Frame, motion turns to emotion.

Dancer Dylan Tedaldi with artists of the National Ballet of Canada in Frame by Frame. Photo: Karolina Kuras.

Dancer Dylan Tedaldi with artists of the National Ballet of Canada in Frame by Frame. Photo: Karolina Kuras.

Given the transcendence and confidence of Frame by Frame, it is easy to forget how singular, even odd, its subject is. McLaren was born in Stirling, Scotland, in 1914 and was the founder of the National Film Board’s animation studio. He won an Academy Award for his 1952 Cold War satire Neighbours (note the Canadian spelling), and his work became emblematic of the NFB to a certain generation, who watched his films in grade school, but he is not a household name in 2018. There is the matter of making a ballet not merely about an animator’s films, but about his life. Frame by Frame is the first large-scale biographical ballet about a Canadian animator, and is likely to be the last.

Enter Quebec director Robert LePage, whose collaboration with the National Ballet of Canada’s principal dancer and choreographer Guillaume Côté to make Frame by Frame is evidently borne of obsession. LePage puts his and his company Ex Machina’s stamp all over the production. (The New York Times’ Alaistar Macaulay’s prickly review of Frame by Frame goes so far as to dismiss Côté, claiming, of LePage, that “the great passages of this production are all his.”) Ex Machina is dedicated to spectacle, particularly to elaborate mise en scène. When the company falters, it is in its breathless, arguably out-dated commitment to the artist-with-a-capital-a, to the romantic, existential sacrifice of creation. When it succeeds, as it does in Frame by Frame, the audience is made to feel both very much like a child and very much like an adult. One is in perpetual awe—surrounded by optical wonder, but poignantly aware of lives lived, dreams dreamed, joys hard-won.

LePage’s heartfelt admiration of McLaren’s work may lead to Frame by Frame’s few blunders (most egregiously, a cheesy, Fellini-esque parade of all the production’s characters at its end) but it is also the essence of its success. I was lucky enough to be invited backstage after the performance I attended, and was reminded of what technology now affords theatre: aside from cut-outs of the two suburban houses from the Neighbours sequence, there are hardly any large props in Frame by Frame. Instead, the mostly empty backstage was full of spikes (i.e., tape markings on the floor for various bodies and movements), dispersed in a figural dance that resembles the paint-and-ink strokes and blots in McLaren’s experimental films. As sublimely choreographic as the recreations of McLaren’s films are in Frame by Frame, and as intricate the technology that supports them, the production wants equally to relate the choreography of creating and collaborating. Many of the work’s best sequences make art out of art-making’s mundane, intimate moments: an early-on contract-signing with the NFB’s John Grierson, in which an overhead camera shows a complex dance of hands on a table; a later-on recreation of McLaren’s well-known 1968 ballet paean Pas de deux, which shows a projection of dancer Jack Bertinshaw as McLaren, looking on at his subjects with voyeuristic fascination.

The audience is made to feel both very much like a child and very much like an adult. One is in perpetual awe—surrounded by optical wonder, but poignantly aware of lives lived, dreams dreamed, joys hard-won.

Those who know of McLaren’s gayness, specifically of the homoerotic dance film he made about the Narcissus myth after Pas de Deux (both films starred handsome dancer Vincent Warren) may find these looks comically leering. But Frame by Frame has subtler things to say about sexuality, and queerness in general. It is, in fact, very queer. McLaren’s life partner was Guy Glover, and in the piece we meet Glover when McLaren meets him, in the 1930s. (They were together until McLaren’s death.) Frame by Frame introduces their courtship through a brilliant sequence in which Glover (Félix Paquet), working as a stage hand on a production of Swan Lake, encounters Bertinshaw’s McLaren, the two dancing downstage for our eyes only; meanwhile, upstage, an audience for Swan Lake faces us, looking not at the gay-male love that we see, but at the heteronormative ballet centre stage. Later, we are introduced to Evelyn Lambart (Greta Hodgkinson), an important collaborator of McLaren’s, who eventually gets her own lesbian pas de deux. Before this outing, we see her dance with McLaren in the animation studio, non-sexually, the two spinning a drafting table (the blank space of which holds a projection of their line animation), and suggesting the generative spaces that queer collaboration can open. With this biography foregrounded, the films seem gayer than ever. Scholar Thomas Waugh has already noted the homoerotics of Neighbours, in which two white, seemingly straight suburban men fight, indeed strip down, over possession of “a very queer flower.” Then there is the literally cheeky, come-close-go-away choreography of A Chairy Tale, McLaren’s 1957 film (with music by Ravi Shankar!) in which a male figure keeps trying to sit on an anthropomorphic chair intent on sneaking out from under his bum.

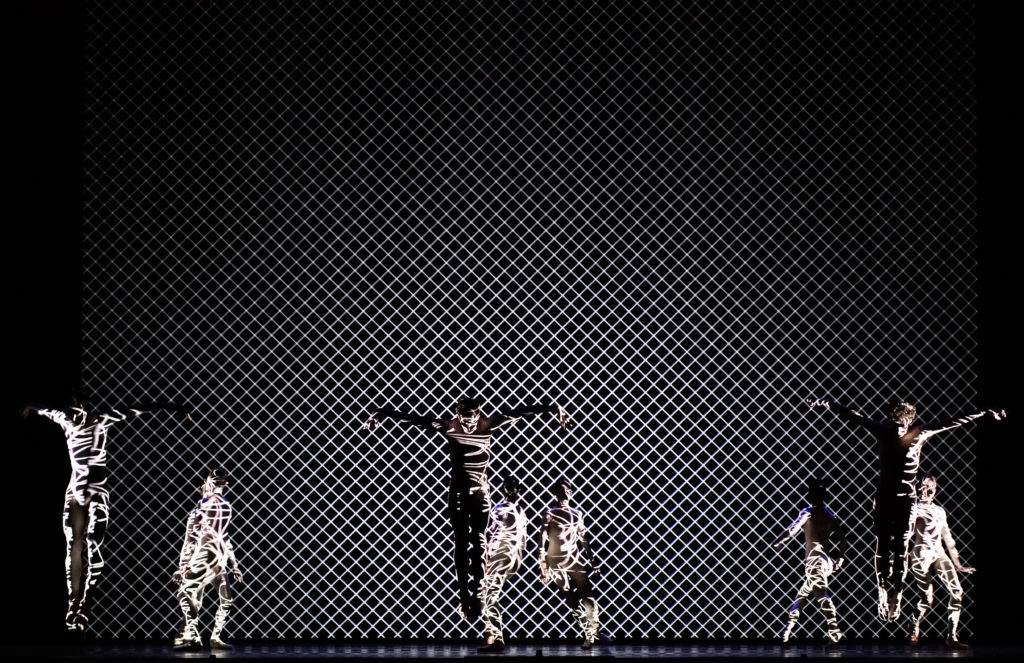

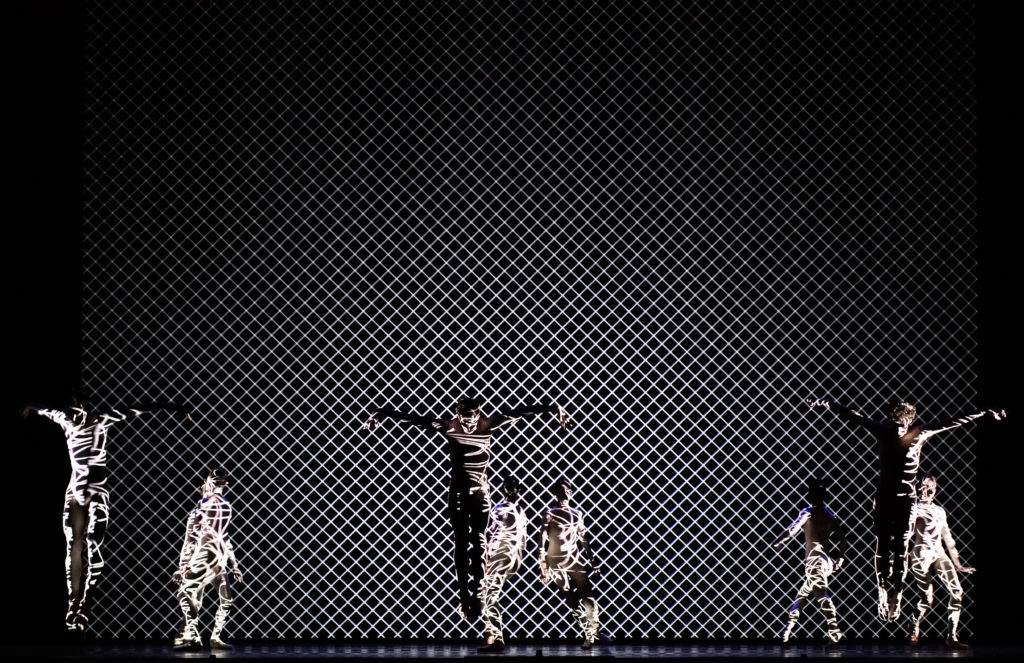

Artists of the National Ballet of Canada in Frame by Frame. Photo: Karolina Kuras.

Artists of the National Ballet of Canada in Frame by Frame. Photo: Karolina Kuras.

It is the constant process of undoing and reconstituting that makes Frame by Frame integrally queer, and contemporary. In the context of the work’s repeated stress on conceptual linkages—between dance and film, Canada and abroad, past and present—one could say that its dedicated theme is the uncommon, non-normative aspects of multiple forms of encounter. It is for this reason that LePage’s kitschy, Orientalist sequence in Frame by Frame depicting McLaren’s visit to Shanghai in 1949 and observation of Chinese calligraphy must be excised in subsequent stagings, particularly as, during the performance I saw, one of two Maoist dancers appeared to be in yellowface. This is notably foul in the context of McLaren’s consistently sensitive work (excepting perhaps the Neighbours sequence, omitted in Frame by Frame, in which the men don “war paint”). There is nothing quite like the short films made in this country by McLaren and his contemporaries: Arthur Lipsett, Joyce Wieland, Jack Chambers, more. As we prepare to see Wieland’s work open the Liverpool Biennial in July, and Frame by Frame light out for international success, it’s a good occasion to remember these precise, critical, elegiac, nuanced and utterly unique works. I am loathe to speak in terms of cultural exports, but these feel very special.