The onset of the current pandemic saw galleries and institutions close to the public and substitute onsite experiences with a wealth of online ones. I know that, for some, these endeavours mitigated feelings of despair and isolation. I personally spent the first weeks of coronavirus life mostly avoiding online panels and lectures, not watching screenings of artists’ moving-image work, not live-streaming performances and especially not clicking through digital viewing rooms. I couldn’t get over the feeling that whatever solace or distraction these things made possible was incommensurate with the enormous loss we seemed to be on the precipice of.

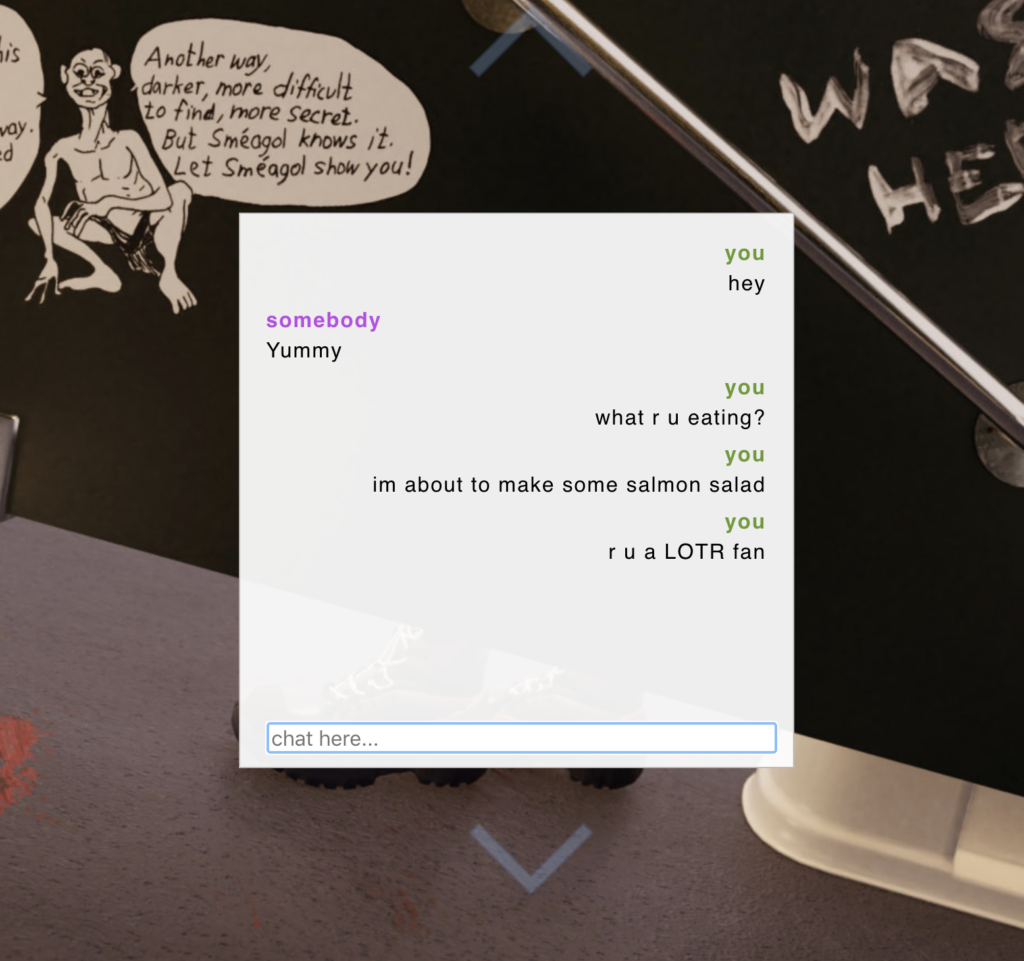

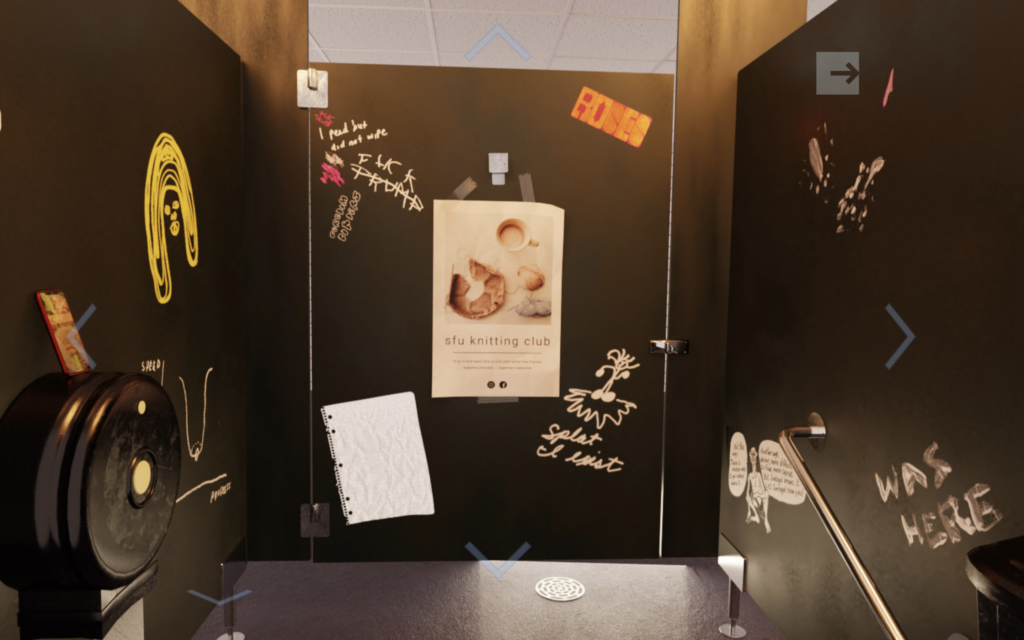

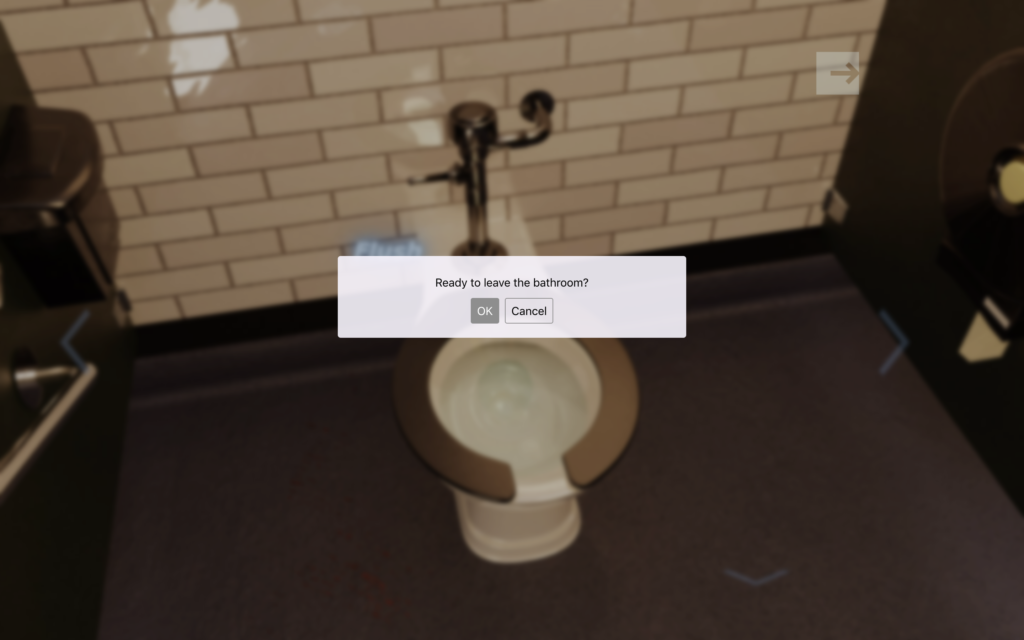

Amid the new pressures of online life, Amy Lam’s

Amy Lam, Make-Believe Bathroom (platform documentation), 2020.

Amy Lam, Make-Believe Bathroom (platform documentation), 2020.

Online programming absents so many of the embodied experiences of seeing art in person. In reinscribing one of those experiences into the virtual landscape, Lam also signals that the bathroom is a basic but important site of bodily accommodation and care. I love that this project thinks expansively about what a bathroom can do, and whom it is for. Beyond its designated functions, the bathroom is also a space for loitering, gossip, intimacy, sex, drugs, grooming, crying, hygiene rituals, unproductive behaviours and many kinds of self-care. As public spaces and amenities have closed due to the virus, so have their bathrooms. Limiting access to private and public washrooms is a protocol that, before the pandemic, already disenfranchised those for whom the safety of time spent outside the home is especially contingent on regular access to bathrooms—for example, gig workers, people who menstruate, people who need privacy to administer their medication, people who care for children—or others who are unhoused or precariously housed. In the wake of the virus, the lack of will or public policy to make washrooms safe and accessible has exacerbated what were already brutal discrepancies between those who have access to private property and those who do not.

Though Lam’s bathroom doesn’t bear any special resemblance to that of the Canadian Art office, lingering here nonetheless makes me think of the moments of brief emotional reprieve that the workplace bathroom once afforded me in the middle of an unprivate workday. The magazine’s staff has been working from home since mid-March, and privacy is, for me, now more the norm than the exception. Previously, those unremarkable moments—of calming my anxiety, checking my phone or briefly resting—had seemed so common, so enduring, so static across time and place as to be outside of history, or in any case I had never before imagined them as part of a reality I would no longer occupy. Lam’s work reminded me, as so many unexpected aspects of the pandemic have, that of course nothing is outside of history, especially not spaces of labour or spaces of the social—private, public, sacred or otherwise.

Amy Lam, Make-Believe Bathroom (platform documentation), 2020.

Amy Lam, Make-Believe Bathroom (platform documentation), 2020.

This review originally appeared in print with the title “Amy Lam.”

Amy Lam, Make-Believe Bathroom (platform documentation), 2020.

Amy Lam, Make-Believe Bathroom (platform documentation), 2020.