“Is it really going to get done?” This is what curator David Liss asks me, somewhat but not completely jokingly, when I see him on September 14 at a media preview for MOCA Toronto.

At the time of the visit, on Friday, there is only one week to go until MOCA’s VIP opening on September 21. And one of the two main elevators is broken. At various places on the five levels of the museum, silver wires and white drywall dust hang in the air; aluminum ladders, red Milwaukee tool boxes and large plywood crates marked “FRAGILE” rest on the floor; the sounds of hammers banging and the beeps of vehicles reversing echo off the 60-inch-thick concrete floors.

In other words, it feels like a race to the finish—a race Liss has been involved in for a long time. He’s been with the museum since 2001, and he seems to be the only staff member who has survived a wave of turnover in recent years. (Everyone else on a staff list from March 2016, just two and a half years ago, is no longer with the museum.)

But on the upside, there is this: on the day that I see him, Liss is helping senior Toronto artist Tim Whiten install a piece on the second floor. Nearby are fantastic new commissions by younger area artists Rajni Perera and Nep Sidhu. Some of the Sidhu works are textile and clothing pieces, the type for which he is already deservedly well-known, but another consists of two pinball machines, one analog and another digital, linked together. Similarly, one of the Perera pieces feels like a risk: a large wooden sculpture, distinct from the striking 2-D images for which she has been lauded. A large, impressive print series by late Ojibwe artist Carl Beam hangs, fully installed, on the wall, the first thing you see when you step off the elevator.

“Yes, it will happen,” says Director of Communications and Visitor Engagement, Rachel Hilton, who is leading the media tour with Director of Programs, November Paynter. Hilton guides us up the stairs to the third floor, where a Barbara Kruger wall piece is already installed, seemingly as proof. But will the museum open, really? After being delayed from May 2017 to May 2018? And then again from May 2018 to September 2018? Later on the tour, Paynter admits, “These things always take longer than you think.”

Tim Whiten’s After Phaeton is part of the MOCA Toronto opening show “BELIEVE.” Photo: Michael Cullen. Courtesy the artist and Olga Korper Gallery.

Tim Whiten’s After Phaeton is part of the MOCA Toronto opening show “BELIEVE.” Photo: Michael Cullen. Courtesy the artist and Olga Korper Gallery.

When the dust has cleared and the $11.9-million MOCA Toronto renovation project opens to VIPs on the evening of September 21—as well as to the public for a free weekend on September 22 and 23—it promises to be a 55,000-square-foot museum quite different from its previous iteration on Queen Street West, when it was known at the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art.

The new MOCA is about five times the size of the old, and is also on five floors instead of one. The new MOCA also doesn’t have the word “Canadian” in its name—there is, as Hilton puts it in an email, “a completely different museum experience for visitors,” including a “distinctly international focus that differentiates the new museum.” As we walk through the museum on the third floor, I see this new focus, too, in the way Paynter, a Brit whose has worked in Istanbul and Dubai, points out works from artists involved in Documenta, like Greek artist Andreas Angelidakis, and the Berlin Biennial, like South African artist Dineo Seshee Bopape, and the Whitney Biennial, like American artist Maya Stovall. This is a far cry from the Queen West Cameron House scene, which once got its own special retrospective at the old MOCCA in 2011.

“We were a very community-based space before, but now we are looking at what other relationships we can nurture,” says Paynter as she guides us through the space. Where the old museum had an ongoing collaboration with the National Gallery of Canada, Paynter mentions that the Bopape work has come from the Darling Foundry in Montreal, another space that has more of what she calls a “kunsthalle” model.

There are also other distinctive features of the new MOCA, like a studio space on the fourth floor where 32 Toronto artists are renting small spaces for the period of one year. The studio project is managed by Akin Collective, an artist-run organization that rents studio space in areas across the city. “We’re super-thrilled to be in the museum,” says Jen Pilles, a freelance illustrator who started renting with Akin in 2013 and became one of its managers in 2015. At MOCA, “we have photographers, sculptors, installation artists, weavers,” she details, but “no toxic materials, no open flame,” for safety reasons. They were also “hesitant to bring in anyone working with clay—too messy,” says Pilles.

The new MOCA, in a shift from the old free-or-pay-what-you-can policy, is also now charging mandatory admission—$10 for general admission, and $5 for students and seniors, but free for those under 18. It also projects doubling its attendance, from the 40,000 visitors annually on Queen West to 80,000 annually in its new Junction Triangle location. “The move to a larger space does more than drop a cultural anchor and tourism destination west of the city centre,” contends Hilton in an email. “It also gives the museum more gravitas, not to mention elbow room. In that space we have significantly more programming, offerings and amenities than our previous operation. This certainly accounts for the difference in admission and thus attendance projections.”

The neon BE:LIE:VE (2002) by South African artist Kendell Geers is also part of the MOCA Toronto inaugural exhibition “BELIEVE.” Photo: Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery.

The neon BE:LIE:VE (2002) by South African artist Kendell Geers is also part of the MOCA Toronto inaugural exhibition “BELIEVE.” Photo: Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery.

But while the new MOCA has cleared many significant hurdles along the way, it has many challenges yet to negotiate. Yes, the lease it has on this circa-1919 automotive and aluminum building—a building being advertised, often, as an attraction in itself—is currently 20 years, with the option for a 20-year renewal after that. But what funding will permit MOCA to get to that point? And what will the neighbourhood—currently an arts hub, but rapidly gentrifying—look like two or four decades from now?

“Our rents are going up, so our incomes have to follow—otherwise we lose our spaces, and there are not many left in the 416 for artists,” says Jesse Purcell, an artist who has a studio in the Sterling Road neighbourhood, of which the new MOCA Toronto is a part. “I’ve been in my spot for five years, and I thought recently, maybe now is the time to look for another studio. But a number of the other buildings I went to look at five years ago are gone; they’ve been demolished for condos. It’s not like there are many options.”

MOCA’s arrival is tied up in those rising rents; the space it occupies was planned as part of condo, commercial and townhouse development announced by the firm Castlepoint Numa in 2015. A Toronto Star story in 2016 detailed how Vanessa Maltese, Lili Huston-Herterich and Abby McGuane, like many emerging artists, have been forced to leave the area due to rising rents. But it’s not only younger artists who have been pushed out. Well-established artist Kent Monkman, who just exhibited at the Canadian Cultural Centre in Paris, moved his studio this May farther north, to the Eglinton and Caledonia area. Monkman’s studio manager Brad Tinmouth states in an email that “We had been looking for a larger and more permanent location for the length of our rental. Raising rents and increased traffic to the [Sterling Road] area were also factors.”

Currently Purcell, along with MOCA, is part of a neighbourhood organization called On Sterling, which recently formed to discuss development and change in the area. “It’s a kind of unique opportunity to have a seat at the table with a whole bunch of actors during this change and development,” says Purcell. “To be blunt, a number of us [artists] are looking for economic opportunities, because otherwise we are going to be pushed out.” And to a certain extent, it’s working for him: MOCA hired Purcell to print some items for the opening season. “They came to many artist studios, door to door, and said, ‘Hi, we’re moving in, what can we do to mitigate immediate impacts?’” Purcell notes of MOCA.

Beyond immediate impacts, though, the future is murky. Notes from On Sterling meetings assert a collective desire to not end up like Liberty Village, another former artist-studio area turned condo/residential. But the city’s own trends, and lack of affordable housing legislation, would seem to override that: “The average rent in the city is $2,400,” says Purcell. “That’s not MOCA, that’s poor governance. The cost of housing and the cost of living in this city is so insane.”

To make things even more complicated for MOCA’s future as an organization is the fact that the condo development Castlepoint Numa was planning to put next to the museum failed last fall in terms of financing and city approvals. While a November 2017 CBC story had Castlepoint Numa’s leader—and past MOCA Toronto spokesperson—Alfredo Romano stating the development would still go forward, recent calls to the his company this week have gone unreturned.

The building the MOCA Toronto is in is next to a reclaimed brownfield. The brownfield was supposed to be home, soon, to condo towers that are also part of the same development MOCA is in—but financing has fallen through. Photo: Arash Moallemi.

The building the MOCA Toronto is in is next to a reclaimed brownfield. The brownfield was supposed to be home, soon, to condo towers that are also part of the same development MOCA is in—but financing has fallen through. Photo: Arash Moallemi.

When MOCA opens its doors this weekend, it may not be the end of a process of change and challenge, but a beginning or continuing of one.

On the positive side, it seems MOCA has truly dodged a bullet in recent years. Plans for the museum released in 2016 under then-CEO and director Chantal Pontbriand—who stayed for all of nine months—intended to call the fourth floor of the museum “The Squat,” a decision in poor taste given the real-estate realities in the area. And for all the drama Pontbriand’s arrival and quick departure brought, it paved the way for the eventual hiring of current CEO Heidi Reitmaier—a Toronto-raised curator with international experience, whose last post was not one of lofty ideas and vision, but a directorship of learning and public programs at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago.

Said Reitmaier in a media statement this week, “We’re beyond thrilled to reveal this unique, wonderfully restored building and our exciting inaugural exhibitions on all five floors to the public and our guests from across Canada and around the world.”

And what will be on those five floors in future, beyond this first season? As we continued on the tour of the building last Friday, Paynter disclosed that the City of Toronto had taken back MOCA’s collection last year, which includes works by iconic Canadian artists like Jack Bush, Paterson Ewen and Betty Goodwin. MOCA is supposed to get the collection back next year in some capacity, Paynter indicated, and is also supposed to find the resources to start acquiring new works—but I wonder myself where those resources will come from, particularly if their private partner in this endeavour, Castlepoint Numa, finds itself under financial strain due to its currently failed land-development schemes.

This question of collections funding also points to the wider issue of MOCA Toronto carving out its own identity and niche—make that a donor-attracting niche—in the Toronto, Ontario and Canadian cultural ecologies. For the time being, their main motto, currently plastered over Toronto’s busiest subway station at Yonge and Bloor, is “Seek Unsame.” But how “unsame” can an institution be when it is showing artists already seen at international events the world over, even if those international events are, to be clear, prestigious and much-heralded biennials?

And already in Toronto region, there is the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Power Plant, the Art Museum at the University of Toronto, the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, the Ryerson Image Centre and Oakville Galleries vying for private and public funding. Many of them focus on contemporary art too. Will MOCA Toronto’s promised mix of hyper-local content—like its studio spaces and local commissions—and international big names be enough to see it through? These are questions some will be watching just as closely as they do the art that the new museum exhibits.

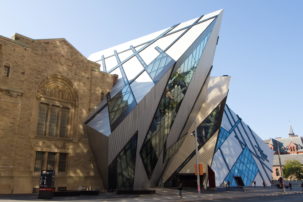

The front entrance to the new MOCA Toronto. Photo: Leah Sandals.

The front entrance to the new MOCA Toronto. Photo: Leah Sandals.