As the winter’s cold sets in, I’m reminded that, like many in and around the region, I come from a place that experiences the intensity of all four seasons. My thoughts jump to questions of what the winter will be like, weather wise, and how this will affect the annual spring seal hunt on Lake Melville (a.k.a. the Bay), Labrador.

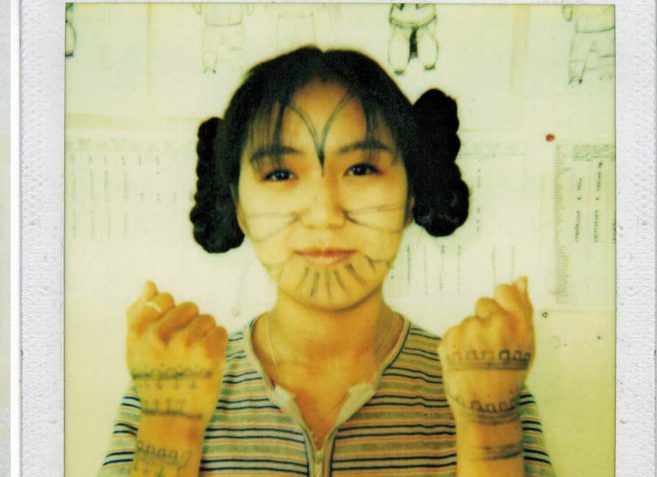

I’m an artist who mainly works in drawing and printmaking, and much of the imagery in my work is drawn from Inuit life and storytelling. Since I’m currently based in Montreal, where I am attending Concordia University and working toward my BFA, the opportunities for me to be out on the land and sea are almost non-existent. I miss being around people who can tell me tales of hunting, fishing and trapping. These “yarns” still fill my imagination, and thus my sketchbooks, with images of our people practising our way of life.

A large percentage of my artistic practice of late—that is, the percentage that does not revolve around my history, struggles with spirituality or the current political landscape of my home in Nunatsiavut—is based on hunting traditions I have experienced myself, or heard about from my Elders in story form.

My favourite stories centre around our annual spring seal hunt, which takes place from about the end of April each year, depending on conditions, until the ice is no longer safely passable. In order to fill the void of missing this year’s hunt, I spoke with Mina Campbell, of North West River, Labrador, about her many experiences out on the Bay, in the Big Land.

Jason Sikoak: Can you remember the first time you hunted seal on the Bay?

Mina Campbell: Yup, I do remember, I do remember. I went with my Uncle Holman. I was probably 15, I think. That was my first year out, and I shot the first seal I ever shot and the last seal I’ve ever shot [with a gun]. So from then on I always use the dart: the unâk and the naulak!

JS: That was going to be my next question—I was going to ask you who taught you!

MC: Yup, it was Uncle Holman. And I’d always go with him seal hunting. Even after I was an adult, we’d always go with him, even after he moved back to Rigolet and I was still living in North West River.

JS: Were there lots of women hunting there back then?

MC: I wouldn’t say there were lots of women, but there were some.

JS: Did Uncle Holman teach you to clean your sealskins too?

MC: He taught me some, but I was taught mainly by my grandmother Edna. She used to clean skins for the hunters back then, and they used to sell them to the fur auction, right? I remember in our house there’d be sealskins hanging over every door, and everything would be in seal grease from the 20th of April or so, for a month.

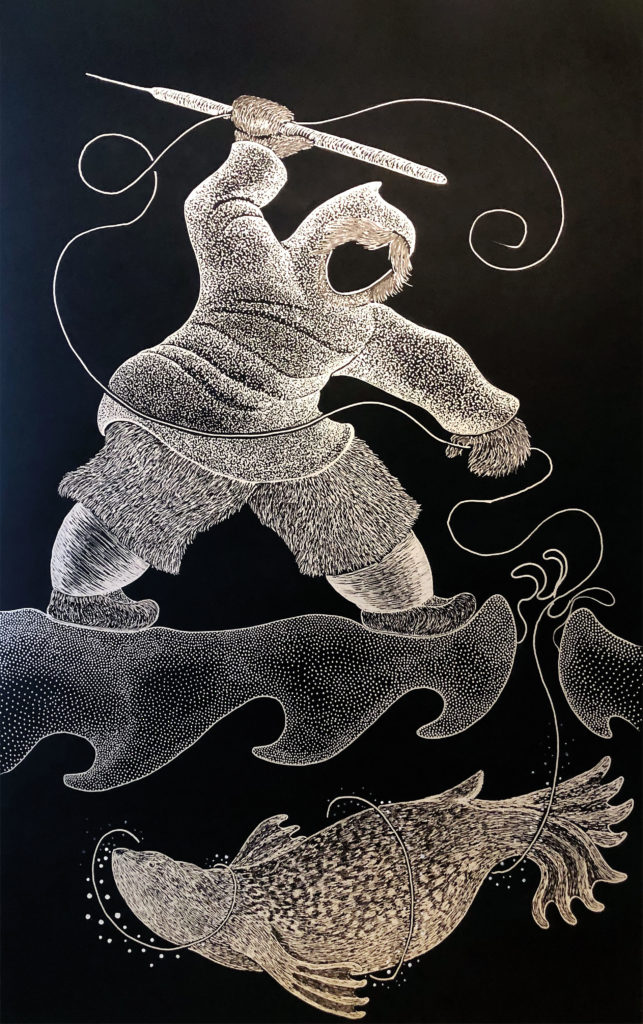

Jason Sikoak, Seal Hunter, 2019. Felted paint on black paper, 101.5 x 66 cm.

Jason Sikoak, Seal Hunter, 2019. Felted paint on black paper, 101.5 x 66 cm.

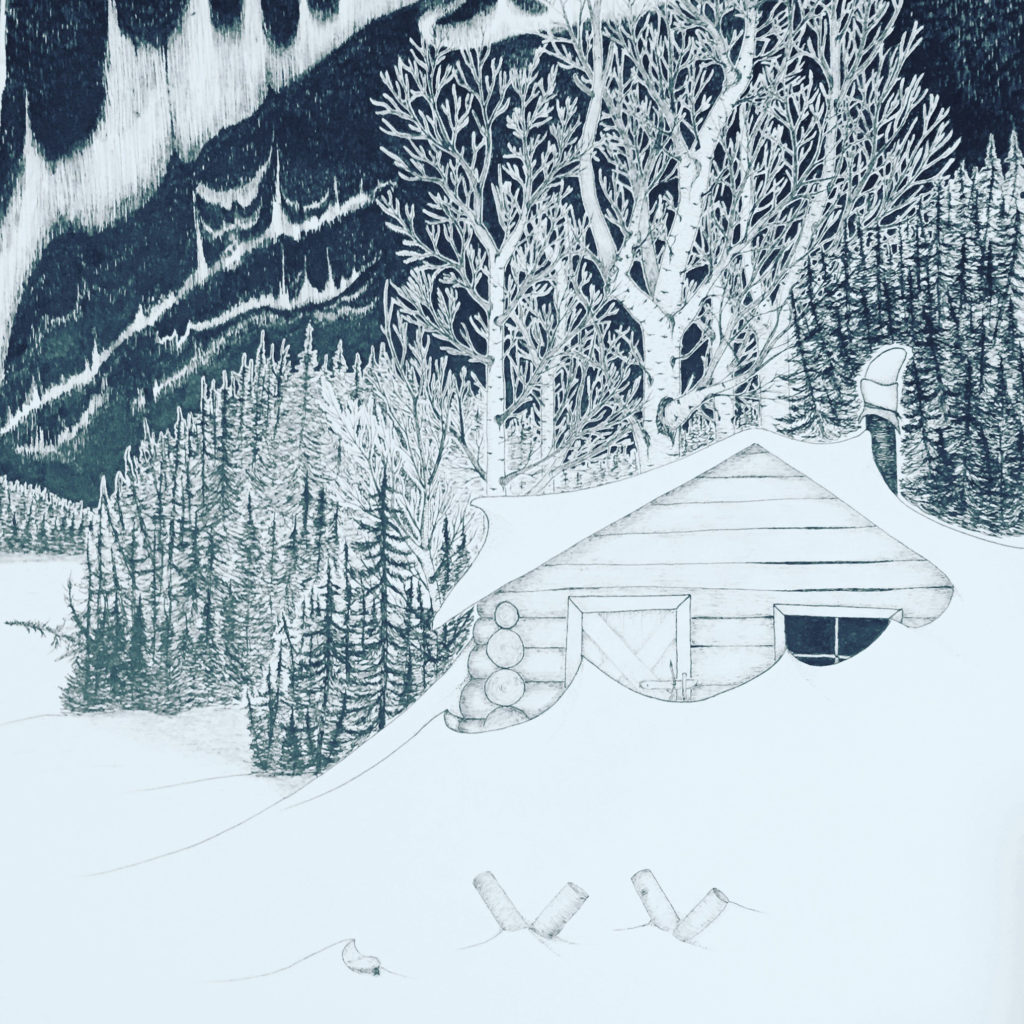

Jason Sikoak, Tilt Under Northern Lights, 2017. Pen and ink on paper, 61 x 45.7 cm.

Jason Sikoak, Tilt Under Northern Lights, 2017. Pen and ink on paper, 61 x 45.7 cm.