Tomorrow, the Art Gallery of Ontario opens “David Bowie is”—the acclaimed exhibition of objects and imagery related to the famed glam-rocker which debuted earlier this year at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum to record-breaking crowds. Here, in a phone interview conducted in June, exhibition co-curator Victoria Broackes discusses the show’s origins, its vital connections to fan culture, and much more.

David Balzer: When this exhibition first opened at the V&A, I think a lot of people were curious about the David Bowie Archive. Can you speak a bit about its nature and provenance? What was it like as a curator to go through all of that stuff?

Victoria Broackes: The first thing to say is that it’s absolutely enormous. It’s like a small museum in its way. There are over 75,000 objects.

But the thing that instantly blew me away when I first saw it was the breadth of it. It has both breadth and depth. The really great thing about it is how it’s not just material that, if you were thinking about the archive of a pop star, you might settle on: the fabulous costumes by famous designers, say.

It actually goes back to schoolboy sketches that show his early thinking, early development. And a lot of the characteristics of David Bowie go back to when he was David Jones—you can see this. For me as a curator, that was the most exciting part. It’s the sketch on the back of a cigarette package, as much as the Alexander McQueen coat. We’re a museum that’s very interested in process. So the fact he never seemed to throw anything away was great.

DB: Is Bowie himself responsible for the breadth of the archive?

VB: Yes. Well, I mean, to be honest, I don’t know the provenance…. I’ve never read or heard or seen an interview with him in which he says, “You know, I had a sense all of this was going to become frightfully important.” I honestly don’t think it came about like that. I think like many things in Bowie’s world, it was sort of a planned accident.

And he just didn’t throw things away. That’s half of it. Also it clearly wasn’t in one place. It was about 10 years ago when he brought it all together. He even got a proper archivist to work on it.

I’m of two minds. On one hand, you think he must have had a sense even back in the early 1960s that one day all of this would be pored over and people would delight in finding the threads in the work. Otherwise, why not just throw it in the wastepaper basket? There’s a sense of that.

And yet, at the same time, that seems improbable, because after all he was in an industry that wasn’t even bona fide art at that stage. So, I don’t really know, but thank heavens he did do this, because it’s a really wonderful collection.

DB: There’s so much to be said about the relationship, currently, between David Bowie and cultural studies. Cultural studies departments have really had a field day with him. He’s now among the most important artist-musicians of the 20th century. What I’m saying is there’s this narrative that has been built around him. I wonder, though—in their time, these shifts in persona must have been baffling, even incoherent. As someone who had access to his archives, did you see more of a real-life through-line? And as a curator, did you feel a responsibility to show that?

VB: The short answer is, not really. I get what you’re saying in that there were no clear lines from one persona to the other, but that’s probably because there just wasn’t. He wasn’t thinking, well, I’ll start in 1971 with Ziggy Stardust and then, you know, carry it through.

The thing about Bowie is that he planned each of the things with great care, but the overall picture, and the impact it’s had, is something else. And that’s what for me comes through. David Bowie is very great and very fascinating and very interesting. Nonetheless, what then happens to those great, interesting, fascinating things is that we the audience take a quantum leap with them, and they become stratospheric in importance.

You know, he didn’t expect when singing “Starman” on Top of the Pops, wearing a Clockwork Orange droog-influenced outfit, that he was going to change the lives of so many people who saw him. And yet it seems that’s exactly what he did.

So my feeling is that, as a young man, he did what interested him—and when it no longer interested him, or if it was in some way causing him harm or angst, he moved on to something else that interested him. And I think that’s what you see when moving on from Ziggy to the Diamond Dogs era. It took the fans by surprise and I think that’s one of the things we like about Bowie: he doesn’t stick to a winning formula, and you see all his peers doing exactly that.

So you get, on the one hand, someone who cares passionately about what people think, and on the other, someone who just goes for it. I think it’s that aspect of being an artist that we respond to.

DB: Everything you’ve said brings to mind the title of the exhibition, which suggests concepts of identity-shifting that are central to Bowie. How did the title come about? It’s so decisive and indecisive at the same time.

VB: Paul Morley, the music journalist and cultural critic, came up with the title. We very much wanted to place the exhibition in the present tense and not declare it as a retrospective, although it has such elements. We wanted to look at ways that Bowie is culturally significant now.

I do think—and I can say this because it’s not my idea—that it’s a brilliant title because it firmly places him in the present tense. It’s a statement, but it’s also provocative and can be ended in any number of ways—which is something we play with throughout the exhibition.

But it also pays tribute to the fact that people have their own Bowie stories. That’s what we find in the viewer coming to the exhibition; it’s a handy way of saying, “Yes, we’re going to show you all these interesting things, but we realize you might have a lot of interesting things to say yourself. And you can take that through with you as well.”

DB: With exhibitions like this, I wonder how much curatorial energy is devoted to recasting the subject in a specifically visual-arts way. I’m thinking of the Alexander McQueen show at the Met—how adamant the curators were about proclaiming McQueen as an artist as well as a fashion designer.

VB: There is a bit of that. [The V&A is], after all, the national museum of art, design and performance. We have been collecting pop-music-related things since the 1970s, though we haven’t done a great deal with them. I’m in the performance department of the museum, so we would in a bona fide sort of way be quite happy to cover a pop-star performer in their own right. However, for a major exhibition at the V&A you are looking beyond that. Bowie is the perfect artist in terms of covering the art, design and performance fields.

With regards to the design of the exhibition, there was a challenge in a sense that the art is in the music, in the performances and in the things we can’t show outside the A/V; they’re intangible. When Geoffrey Marsh, the other co-curator, and I came back from the archive, the first thing we said is that we didn’t want this exhibition to look like anything we’ve ever been to. Working in a museum such as this, however much you go in thinking it’s about the A/V and sound, you also think about how you’ve got some objects to show—you know, cases and screens. And we decided that’s absolutely not the way we wanted to treat this.

So we started with the sound and vision and worked out the objects. We went to theatre designers—of course, we have quite a lot to do with them in my department anyway. But it seemed, in a way, a bold step, at least a challenging step for the museum, which treats every object in exactly the same way in terms of conservation, display and those things.

59 Productions were our theatre designers, and had worked mainly in live performance, theatre, opera—they’d done the opening ceremonies at the Olympics. We brought them together with a more conventional exhibition designer, and this made it possible to do something much more theatrical, which we thought was essential. We were dealing with a subject about which people feel passionately and we had to try to find a way of making an exhibition not only where you could learn a lot and think a lot, but also where you could actually feel.

DB: That makes me think of the photographic component of Jeremy Deller’s installation for the British Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale, which includes photographs of Bowie’s fans in the early 1970s. Bowie’s fans are so vital to an understanding of him. How did you incorporate that experience into the show?

VB: Yes, it’s the fans’ response that is the really extraordinary thing. And it was a difficult thing to actually address in an exhibition. We thought hard about it.

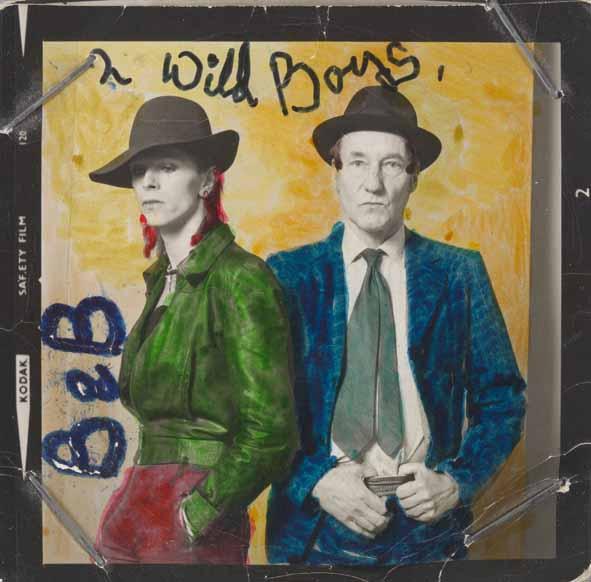

There is the work of one fan in the exhibition. He happened to have become a professor of fashion at the Royal College of Art. But he was one of those 14-year-old boys, living in the country, gay…an outsider, basically. He saw that performance of “Starman” and it changed his life. He credited it to putting him on the road to where he is now. At the time, he created these absolutely fabulous scrapbooks of cuttings. He made badges. He made a painting of Bowie and sent it to him, and Bowie’s mother wrote a letter back—which we have in the exhibition! It really takes you back to a different era, where everything was sort of… cozier. Clearly one person can’t speak for everybody, but in a sense he represents an aspect of what Bowie seems to have done.

Until the show opened, I hoped and prayed that we had kind of, you know, done it well. It was the most challenging exhibition I’d ever done, and I put everything into it. But it wasn’t until the audience came in on the first day that I thought, “My god, maybe we actually have got it, have done it.” Because again, it’s all about the audience—until they’re in there, it’s dead. Then it comes to life.

So yes, I’m acutely mindful of how important the fan is to Bowie. And we were thinking about it all the way along. The impact of the exhibition has taken a leap beyond anything I had ever expected or hoped for. That’s the Bowie effect.

DB: As someone who’s privy to the archive, can you outline some objects that will be of interest to fans who think they’ve seen it all?

VB: There’s quite a lot. Much hasn’t been out in the public domain.

You’ve seen the costumes in performances, but very few people have seen the costumes up close. They’ve been in Bowie’s hands. So you’ll see them for the first time, and that’s thrilling.

Also, the lyrics: they blow you away. Even the crossings-out. You see how he thought this, then he thought that, then he came up with the final idea. It’s a total inspiration. You see the musical notations he did for “The London Boys,” for instance: four parts that he wrote out, learning to write music out of The Oxford Companion to Music, which we have showing next to it. It brings tears to my eyes, actually. Bowie doesn’t say, “I can’t do that, so I won’t.” He says, “I can’t do that, so I’m going to get that book and learn it and do it and try in my own way to perfect it.” If we all did that we’d go a lot further, perhaps.

One thing I was completely thrilled to find were the storyboards to a film he wanted to make after the Diamond Dogs tour. He was interested in making it into a musical, then he turned it into a stage show and following that he wanted to make it into a film. So here we have showing, for the first time ever, the storyboards he did, beautifully drawn, along with a film he made that is actually very experimental. I read in Nicholas Pegg’s The Complete David Bowie about that project—did it exist or not? But to find all of the stuff proving that it did exist…. It was really thrilling.

There’s lots in the show that’s never been seen before. There’s rare film, again pertaining to Diamond Dogs. I think the whole Diamond Dogs thing is very interesting.

DB: It’s funny, when you think about all the gossipy stories surrounding Bowie at the time, and then look at what you’ve collected here, and consider his creative life—he seems almost superhumanly prolific.

VB: I know! Along with not being constrained by your area of expertise and just working it out, the other part of the story is just actually working incredibly hard. My colleague, who’s keen on stats and figures, worked out that over a 32-year period, Bowie performed once every 11 nights. Imagine that. And of course that’s on top of producing 26 albums, other people’s albums, making films and videos, writing and producing songs for other people…. It just beggars belief, the prolific nature of his output.

DB: And on top of that, all the drugs! Although perhaps they helped…

VB: [Laughs] Well thank goodness it’s not only that. That would be depressing. All I’ll say is that they don’t seem to have stood in the way at all.

This interview has been edited and condensed.