Joële Walinga, Cave Small Cave Big (film still), 2016, 11 min.

Joële Walinga, Cave Small Cave Big (film still), 2016, 11 min.

Cave Small Cave Big, Toronto-based artist Joële Walinga’s first film, was written by two five-year-old girls. It premieres at the Art Gallery of Ontario on February 16.

The surrealist short film begins with Butterfly Girl sleeping through a mad scientist breaking in and stealing her cave. Kristen the Ogre and Nana the Troll are both women characters; Kristen wants to marry Nana in the cave.

“They have you thinking that you’re just watching this superficial, non-sequential series of events, but each character is dealing with their own issues with the transience of ownership and how to deal with loss. As soon as you get into the cave story, it’s gone. You’re just getting into Butterfly Girl catching the butterflies, then suddenly it’s Leaf Girl,” says Walinga.

“It’s a story about these characters who can’t own anything, and they simultaneously put the viewer through that experience. They never linger on a storyline, so you can’t own any storyline as a viewer. You experience loss because you never get the satisfaction of closure with what happens to any of the characters. So the viewer experiences loss at the same time that the characters do.”

Nodding to the conceptual tradition of setting parameters for a pursuit and committing to it regardless of its tediousness, Walinga recreated every prop, costume and narrative development that Madeline Harker and her best friend Adelaide Schwartz storyboarded. “I had a rule where I couldn’t say no to anything and I didn’t want to guide anything. But I asked them questions,” Walinga tells me. We discussed her commitment to the demanding process, and the challenges involved when collaborating with children in good faith.

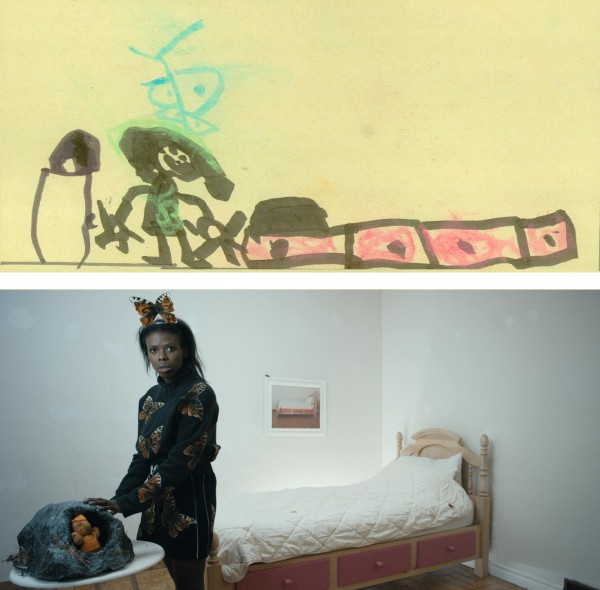

A drawing by Madeline Lee Harker and Adelaide Schwartz (top) and (bottom) a film still from Joële Walinga’s Cave Small Cave Big, 2016, 11 min.

A drawing by Madeline Lee Harker and Adelaide Schwartz (top) and (bottom) a film still from Joële Walinga’s Cave Small Cave Big, 2016, 11 min.

Merray Gerges: Tell me about the process.

Joële Walinga: The workshop was three days long at Videofag. We watched movies before they started writing. They picked The Princess Bride and Frozen and How to Train Your Dragon and some animated film about the Day of the Dead. Then they designed and drew all the characters. I designed and sourced everything to match the drawings as closely as possible. I made all the costumes and Alicia Nauta built the cave and did art direction.

For Leaf Girl’s outfit, I sewed every single leaf—maybe 300 or something—onto a basic T-shirt and shorts with a sporty shape. I didn’t want them to seem too fantastical, so the foundation of the other costumes is fleece sportswear. The outfits of Kristen the Ogre and Nana the Troll were hand-sewn because I didn’t have a sewing machine. The shoot was two days long. It’s been a long time for an 11-minute film. To be going on two and a half years? That’s wild. I had very little money: $6,000 from a grant and $3,000 from the crowdsourcing campaign. Post-production alone cost $4,000.

Joële Walinga, Cave Small Cave Big (film still), 2016, 11 min.

Joële Walinga, Cave Small Cave Big (film still), 2016, 11 min.

MG: How aware were Madeline and Adelaide of their position as your collaborators?

JW: They wanted to play, because that’s what kids want to do. I’d tell them, “Let’s do this first, then you can play,” and Adelaide said once, “You know what? You might think that you’re in charge, but we’re the writers, so we are actually in charge.” She was bossy.

Yet they couldn’t fathom that we were making a film, because they had never considered the possibility of filmmaking. Films are telling them what the world looks like and informing how they make decisions about it, but if they don’t know that films are made by other people, and don’t understand that they’re fabricated, they take films as truth—and that’s really dangerous.

MG: What became clear about their psyches and their gender conditioning?

JW: I was expecting the girls’ story to be more indicative of normative gender conditioning, [for them] to write about princesses. But they didn’t write something that has anything to do with the outside world. Compared to the other workshops in this project series, the boys stuck to gender stereotypes and wrote stories with gun violence, fighting, zombies. But the girls’ story is like if you turned the channel to an alien TV station. It’s so bizarre.

The most confounding thing to them right now is probably ownership—hearing at school that they have to learn how to share. I think at that age they’re exploring what it means to own and they’re trying to understand why they can’t. Butterfly Girl doesn’t learn: she made a cave and it’s stolen from her and that hurts her, but then she tries to catch a living thing and cage it, and doesn’t see the irony.

Joële Walinga, Cave Small Cave Big (film still), 2016, 11 min.

Joële Walinga, Cave Small Cave Big (film still), 2016, 11 min.

MG: Of course they didn’t anticipate how their story would present logistical difficulties for you—with the butterflies, for example, or finding a cave and making a replica of it.

JW: Finding a cave was hard: I had to call different parks to get permits and had to pitch the project because I wanted everything for free. With the butterflies, I went for Painted Ladies, which are the Monarch’s ugly cousin. Their bodies are hairier and bigger—they’re more insect-like. Butterflies are kind of gross. They’re just ego insects, with make-up on.

This is my Yelp review for the butterfly-breeding company: It’s $120 for 10 butterflies and they come frozen in a Styrofoam box, where they’re in a coma until you thaw them two hours before you need them. So we got the set ready and I wanted Butterfly Girl to be in the room with butterflies flying around her, but when I opened the box, they were so languid. They didn’t fly away at all. They were like teenagers on spring break lounging on the couch. I was grateful it wasn’t my wedding.

Joële Walinga, Cave Small Cave Big (film still), 2016, 11 min.

Joële Walinga, Cave Small Cave Big (film still), 2016, 11 min.

MG: What sparked your interest in working with kids?

JW: I used to be a nanny. I took a two-year-old to a train track because he liked trains. I told him I had just returned to Toronto from Halifax via train and he asked, “Why were you on a train?” I said I moved back from Halifax. Then he asked, “Why were you in Halifax?” and I said I went to school there. Then he asked, “Why’d you go to school?” and I said, “Well, I didn’t feel like I was doing enough,” and he was like, “That happens.” He said “That happens”! He’d probably heard it from his parents, then remembered it and parroted it when he sensed the appropriate time.

I’d been keeping my interest in social work and community engagement out of my practice until a project where I made a sculpture and posted it on Yahoo! Answers and asked people if it’s a good sculpture, then exhibited it with their responses in the gallery. Then in What Colour Should We Paint This Chair? I set up a hotline for people to call and tell me to paint a chair in any colour and watch through a live stream. I painted two layers of each colour, even the bottom of the chair, so that each layer was 100 per cent opaque.

Joële Walinga, Cave Small Cave Big (film still), 2016, 11 min.

Joële Walinga, Cave Small Cave Big (film still), 2016, 11 min.

MG: Your audience becomes your collaborator and you give them complete control within the parameters that you set, then they develop problems for you to solve. You’re totally obedient to them regardless of the difficulty or absurdity of their requests. You made the film as true to the kids’ drawings as possible. You painted the chair in every single colour or texture the callers asked you to.

JW: I did. I would be ashamed of myself if I hadn’t. It would’ve ruined the whole thing. There are things I would’ve very happily not done—huge obstacles that sucked, and cost a lot of money. But it would’ve been a total waste of time if I hadn’t listened to even one suggestion. The project only works when you’re 100 per cent committed to it. You can’t half-do it.

I’m getting good at production problem-solving, though. For a couple of years I’ve been [restricting] projects with rules that have made me really unhappy. I was really unhappy during the [chair] project because I had the most horrible job in the world: painting a chair over and over in silence. Cave Small Cave Big was grueling work. But the point is that I don’t have to like it. My intention is not to enjoy the process.

MG: Are you a masochist?

JW: I’m not a masochist, but I definitely don’t believe that [making] art should be enjoyable for artists. I’m not one of those artists.

Joële Walinga, Cave Small Cave Big (film still), 2016, 11 min.

Joële Walinga, Cave Small Cave Big (film still), 2016, 11 min.

MG: What’s the next iteration in your series of short films written by children?

JW: Nightmare Here follows two dog owners navigating the apocalypse. It’ll take place between a mall and a hospital. It’ll have dogs, a horse, zombie extras. It’ll cost $80,000. The woman in it falls off a balcony and he grabs her hand. How am I going to do that? There’s a horse in it. There’s the soul of a dead horse in it. I’m going to have to hire a horse soul. And the zombies will need lots of make up, though I want to keep them kind of casual. Just freshly dead. Casually dead.

Cave Small Cave Big Trailer from joële walinga on Vimeo.

Cave Small Cave Big premieres at the Art Gallery of Ontario on February 16 at 7 p.m. Free tickets can be reserved here.

Joële Walinga, Cave Small Cave Big (film still), 2016, 11 min.

Joële Walinga, Cave Small Cave Big (film still), 2016, 11 min.