In 2014, New York–based, Toronto-born artist Gareth Long was the first curator-in-residence at Vienna’s Kunsthalle Wien. The stay resulted in two projects. The first is a Tony Conrad exhibition, running to March 8, for which Conrad installed a replica of a prison cell that was the setting of a 1980s experimental film he made with Tony Oursler and Mike Kelley.

The second is “Kidnappers Foil,” which opened in mid-November and runs to January 18. This, in Long’s words, is his chance to “play a little bit with that intersection of artist and curator, and actively muddy the waters.” The exhibition collects the extant work of obscure American filmmaker Melton Barker, who travelled to various towns across America producing the same film over and over, exploiting people’s relatively newfound desire for cinematic fame.

Long talked with David Balzer in October in advance of the project’s opening, touching on its relationship with film history, ethnography, the archive, repetition and more.

David Balzer: Can you briefly introduce us to Barker and what you plan to do with his work?

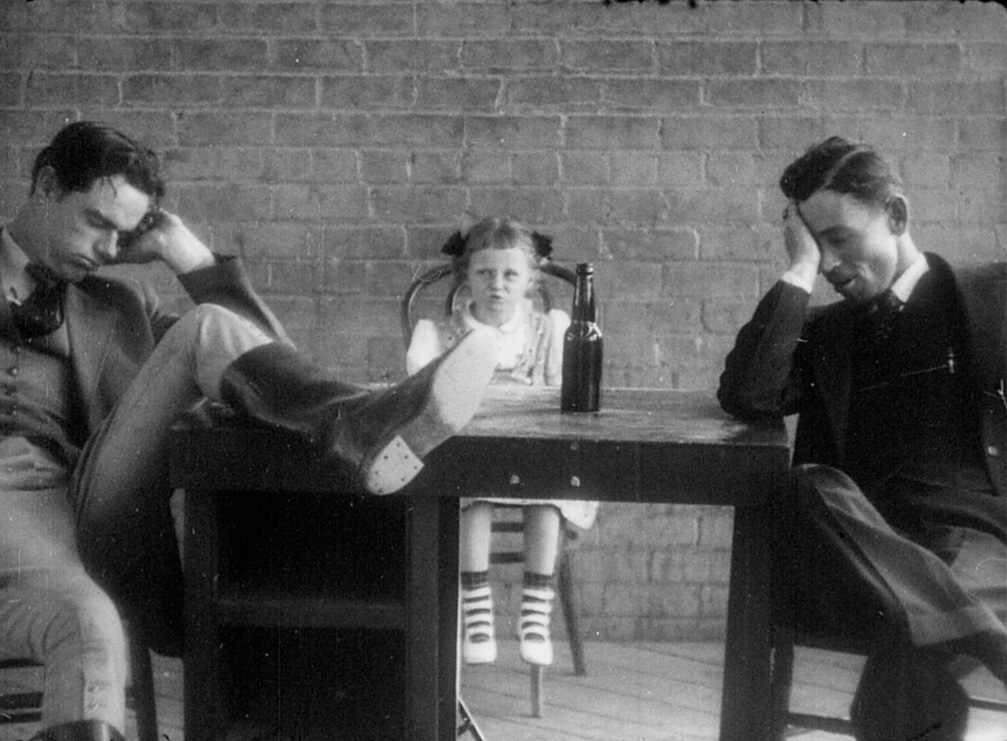

Gareth Long: In 1936, Barker went to a small town in Texas and said, “Hey, none of you will be famous, but wouldn’t you like to see yourself in a movie? Why don’t you all give me a dollar and we’ll make this film together, and we’ll organize a screening, and then I’ll leave the film behind?” So a whole bunch of them gave him a dollar and he made this film. It’s a very simple plot, about this little girl, Betty Davis, who gets kidnapped from her birthday party; the local kids have to band together to try to rescue her; they do; there’s a celebratory party at the end that comprises a song and dance, a local talent show.

So he makes the film, screens it, goes to another small town and makes the same film. Exact same script but new local kids. And then he goes to the next small town and makes the same film, again and again and again. He makes between 100 and 300 versions of the same film, from 1936 until about 1972.

So you have this really interesting moment of a cinema that is outside the scope of Hollywood. And even though it’s playing with this genre that would be found in classical cinema, it’s this fascinating look at iteration, difference and repetition. This guy was copying or quoting himself. I’m interested in this idea of an unlocatable original. These are all original, yet none of them is.

Right now, there’s an archive in Texas that houses the Barker films that have been found, and there are 14 of them. That’s it. Because, at the time, nothing about these films seemed to warrant a need for preservation or conservation. So the films that have entered this archive have come in on a bunch of different formats. Some have come in on film, but some were recorded on VHS when the film was broadcast on a local television station. You have this weird question of media histories.

So for my exhibition—and I’m calling it that, and not an exhibition of Melton Barker’s works, even though his works are the material with which I’m making this installation—I’m presenting the 14 versions of The Kidnapper’s Foil all at once, in the gallery. So, not film screenings, but 14 projections. Because of these aforementioned media problems you have quite terrible sound quality for some of these films. Some I can listen to with headphones and still find hard to understand. There’s this interesting ethnographic or anthropological thing going on, because if you look at the films from 1936 versus the ones from the late 1950s, of course the dress is different, but you also have local accents. He was going all over the Southern US. He got quite close to the Canadian border at one point.

Some of the films will have headphones and some speakers, but, generally speaking, it will be a wash of sound. All of the films will be playing at once in the exhibition hall; the videos will bleed into one another. And they’ll start off in synch, but they’ll fall out of synch. And some will be black for a while as the other ones catch up. It’s both one film and many films.

DB: Is there a great variance in length?

GL: There are some that are around 25 minutes, some that are around 12. Some will be black for quite a while. Because it’s in Vienna and the sound quality’s tough, I’m also making the script available, and I’ll have a few essays—one by the historian who’s working on the archive, Caroline Frick, and one by Erika Balsom, who’s a film studies professor at King’s College London, originally from St. John’s; she’s written about my work before. Her first book was about exhibiting cinema, so she’s kind of the perfect person to talk to about this. The script will be in vinyl lettering in the space, too. I don’t want to subtitle the films; I don’t want to adorn them.

DB: How did you come across Barker’s work?

GL: To be honest, I think it was one of those Internet rabbit holes you end up falling into. I was searching around and found something; I think one of them had been entered into the International Film Registry in the US, and I had come across a list of what had just been entered, and followed a link and found out the whole backstory of the same guy making the same film over and over again.

He’s sort of on the border of being a huckster. He kind of isn’t, but he kind of is. This is how he was making his living for so many years.

DB: How much of a living did he make?

GL: I don’t know. It’s hard; no one was really documenting this whole thing as a project. At the time it was just a guy doing his thing; it’s only interesting to us now. At the time I don’t think he was getting rich, but he was surviving off of it.

DB: Are there any surviving Barker family members?

GL: I think it’s mostly fallen into the hands of Caroline Frick at the Texas Archive of the Moving Image. She’s the de facto expert on this, the one I’ve been dealing with the most in terms of getting the films, getting the permission. She’s been extremely generous and very helpful.

DB: So are you showing every extant film?

GL: There’s a possibility there might be two more that might be with the Smithsonian, but they haven’t been released to the archive. I’m not certain of that. But of the ones we know exist, I’m showing all of them. There’s 14.

DB: Is there anything you can say about form meeting content in terms of the narrative of the film perhaps reflecting this odd filmmaking process?

GL: I’m going to add a bit of a weird twist here. I also did a degree in classics at the University of Toronto. So one of the things I found fascinating is, I’ve been doing so much work about copying and iteration and uncreative writing, that I love that the word for “plagiarism” actually comes from the word for “kidnapping.” Martial talked about how someone was kidnapping his words. It was “plagiarius,” which turns into “plagiarism.” I love the idea of someone plagiarizing himself, kidnapping his own contents again and again. It’s a stretch, but for me it’s a nice little connection.

Regarding the form and the content, it’s actually doing the opposite, turning it on its head. This thing that was always supposed to be local, always supposed to be seen by those who were in it, is now functioning as the opposite: it’s seen by people who are always alien to it. But it prefigures a lot of stuff that’s happening in current production, especially current new-media production, which has so much of the amateur built into it. All of the actors are amateurs. They’re all kids who aren’t very good at what they’re doing. And the narcissism and the desire to have the camera on oneself—we think of that as such a current trend, but this is more evidence that, since there were cameras, people have wanted to be in front of them.

The plot ends in a talent show, a party with song and dance. But let’s say in one town, little Billy is a really good dancer, but in another, little Sally’s a really good singer. That’s the only part that changes. You get these local talent shows; this also prefigures a lot of reality-TV competition shows.

DB: Was Barker forthright with the people he was filming that this was a franchise project?

GL: I think he was pretty open. They knew there were other films around of the same ilk. His claim to fame is that he says he discovered Spanky from The Little Rascals. It’s one of the ways people took him seriously and why they agreed to be in these films. There are photos of him with Spanky. I don’t know when they’re from. Part of it was this idea that you’ll be in this film and who knows…maybe someone will see it and you could become famous. He’s preying on that desire for fame. But yeah, they advertised for these films in the local papers, so it’s not like it was ever hidden. It was about the local gang. It wasn’t about “look at the new film”; it was about “look at yourself on film”—you get to see your local community. The community could watch the community onscreen.

DB: Do you have a favourite?

GL: Kind of the first one we have, which is from 1936, from Childress, Texas. This is partly because the quality is so good. It seemed like he cared a bit more at the beginning and got sloppier as he went along, phoning it in. It’s on film so the quality is more precise.

I mean, they’re not that good. None is particularly great. They’re more curious than anything. And here I am: I’m going to subject people to watching 14 of them. It’s more liking them as a fact, than liking them as films.

Gareth Long’s “Kidnappers Foil” continues at the Kunsthalle Wien until January 18.

This interview has been edited and condensed.