Brad Phillips’s preferred meeting place in Vancouver is Reno’s Restaurant at Broadway and Main. “It’s quiet there, and we will be able to talk,” he says.

In the condo-choked gloss of Canada’s most beautiful city, Reno’s offers a step away from the fray. Albeit of a dying breed, Reno’s is the type of diner you can find pretty much anywhere on the continent. In keeping with Phillips’s practice as an artist, it’s situated at a studied remove from current trends.

As Christopher Brayshaw, the Vancouver critic, photographer and co-founder of CSA Space, remarked to me, an artist concerned with appearing hip would never reference John Cheever. But Phillips does (Unknown Painting, 2005), and Cheever provides a revealing clue to understanding the appeal of Phillips’s art. A paragon of WASP experience in the mid-20th-century US and the writer of matchless tales of suburbia, Cheever created fiction whose power lies in intimations of dark undercurrents that run through domestic life. Phillips makes art with a similar effect. He is an artist who takes photographs and makes paintings in a photorealist style (meaning photorealism is less a goal than a by-product of his practice, but more on that later). Like refractions of light through a crystal, his work creates surface tensions with what’s left unsaid.

A Toronto native, Phillips moved to Vancouver in 2002. Like Cheever, whose relationship to pop culture is at this point etiolated at best, Phillips makes work that appears to have little in common with his city’s dominant art practices. Photography is central to his work, but he uses the medium more as a tool than as a mechanism deployed to reflect back on the genres photography creates. This is not to say Phillips’s work lacks an international audience. Represented by the Zurich gallery Groeflin Maag until it closed in 2010, Phillips is an artist arguably appreciated more outside his home country than within. His work has been purchased by some noteworthy collectors: Toronto financier and philanthropist W. Bruce C. Bailey was an early supporter.

It is possible Phillips’s work flies beyond the sightlines of full art-world appreciation in Canada because he makes art in a fashion that is deceptively straightforward. His work is plainspoken in a way that is perhaps more intelligible to the European eye. Phillips hews a vernacular style that constructs a world from the materials at hand, as evidenced by his habit of making paintings about books he has read. One Month of Reading in the Mirror (2007), for instance, presents a stack of books by the writer Patricia Highsmith, their spines cracked from use. Not surprisingly, Phillips, a maker of paintings, gives his literary references a surface form. He presents books to be judged by their covers, so to speak. For an exegesis of their references, viewers will need to look elsewhere—including to other works made by the artist.

The implied deferral of significance between works is the method by which Phillips constructs an edifice of meaning through his practice as a whole, his titling of a work being a pointed element within the piece’s overall composition. This is especially true because his work is always figurative with a focus on the still life (Sentimental Monochrome, 2009) or landscape (Summer of Whatever, 2003), and he has made many paintings in which the signifying element is reduced down to a declarative text. The work Richard Prince (2009), for instance, is a painting of a piece of paper taped to a wall, with a note scribbled on it that reads like a one-liner from Prince’s own Joke series (1986–ongoing): “I wish I’d been able to speak to my father before he died, so I could tell him to go fuck himself one last time.”

The punch line hits its mark, but it gets a laugh that’s more queasy than funny. Richard Prince poses questions about which components of Phillips’s work are autobiographical, as the reference made to the work of the American artist seems less a clever homage than a discreet form of self-revelation. Similar conclusions can be inferred from the text painting Doctor Shopping (2010), which features a tightly framed list of doctors’ names on a black background. The slight angle given to the list of names and the shadowing in the lower right-hand corner subtly position the viewer, and more explicitly the artist (Phillips is tall), as if perusing the list within the lobby of a medical building.

Brayshaw notes that Phillips’s painting technique is “faux naive”; the artist’s photorealist style risks the appearance of simplicity. Close inspection of the canvas reveals great painterly skill, but it is a technique deployed as a means to an end. Phillips avails himself of a dry finish when applying paint to the surface of the canvas. It is an effort made in firm disavowal of the drama of the brushstroke, and also a way for the artist to maintain a fidelity to his pictorial goals.

“There are no happy accidents in the making of my work. I know exactly what the painting is going to be when I start, and that’s how it looks when I finish. In between, nothing happens except execution,” Phillips says. In a similar fashion, he uses titles to banish ambiguity, all the better to summon full engagement with his works’ melancholic ambience.

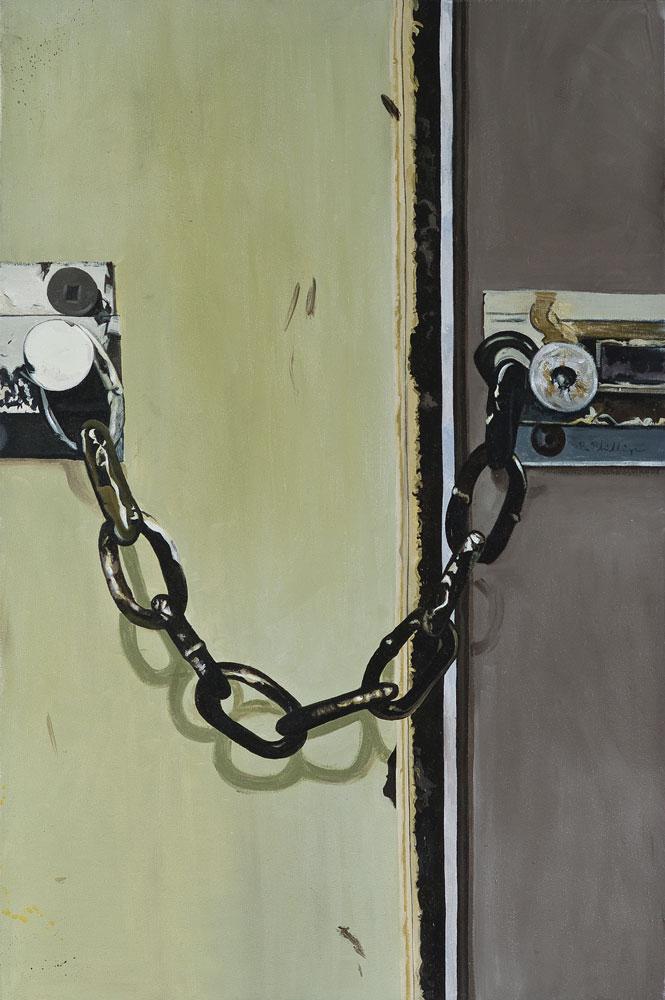

In making his works, Phillips uses a camera, but he reports that he mostly knows what image he wants before he takes a photo. While he sometimes exhibits the photographs he takes, they mostly become the bases for his paintings. At each step in the process, Phillips excerpts and revises. Every component in his repertoire—whether paintbrush or camera—is only a tool to facilitate his exceptional talent for pictorial composition. One Month of Reading in the Mirror presents what we assume is a gathering of books read, but this record from the artist’s life is angled, as if seen in a mirror. In this way, Phillips constructs a metaphor for self-reflection: we are what we read, so to speak. Another work, Major Depressive Episode (2011), features a chain lock on a door in close-up. The focus on this detail, combined with the work’s title, is almost cinematic in effect, its impact deriving in part from an implied honesty about the artist’s circumstances.

Rather than being painterly or expressive, Phillips makes artworks in the service of narrative. He has a story to tell, and each painting is not so much a chapter as a sentence in its overall composition. A Modern Painters review of the artist’s exhibition at London’s Residence Gallery last year notes that Phillips focuses on details as if “he had zoomed in until his eyes reached the satisfying flatness of the written word.” Literature finds an equivalency in the clarity and flatness of Phillips’s skill with pictorial denotation.

Phillips’s use of a realist style and his dry application of paint give his work a certain verisimilitude. In the words of John Cheever: “Verisimilitude is…a technique one exploits in order to assure the reader of the truthfulness of what he’s being told.… Of course, verisimilitude is also a lie.”

Phillips uses visual art as a means of self-portraiture. He authors certain truths about himself through the fiction of painting. In the midst of the current ethos of Internet and reality TV–based self-disclosure, his modus operandi strikes one as almost old-fashioned. As Vancouver writer Kevin Chong notes in conversation, Phillips’s work is self-revelatory, but not in the style of the up-to-the-minute Facebook status update. Making paintings is, after all, hardly the quickest way to get your message across. The same could be said of the presentation of art exhibitions. Art occasions slowness and contemplation, which, as the American artist Kerry Tribe has noted, is a proposition that is a “tiny bit radical” when considered in relation to the value today’s culture places on instantaneous content transmission.

Phillips concedes that in recent years his work has become more directly autobiographical. The Victoria-based fiction writer and critic Lee Henderson notes in an email that Phillips’s earlier work tended to favour what Henderson calls “goth girls [Untitled, 2001] and other midnight imagery: a van parked in a vacant parking lot in front of a black sky [The Last Party, 2002], a silhouette of a forest at night and so on.” The imagery, Henderson says, was in keeping with “a young man’s experience.”

Today, Phillips’s work is both subtler and more polished. Perhaps not coincidentally, he matches advances in his painting skill with the recognition of the value of his life as subject matter. His directness of expression, however elliptical, is a measure of his confidence as a maker of artworks, an assuredness that belies the self-recriminating eye with which he often seems to regard himself.

Phillips admits that this new tendency to make works that refer more directly to his own experience leaves him feeling exposed, though he has found that his audiences recognize the vulnerability he risks and respond accordingly. When he cites influences, other artists hardly figure, although he does count himself a fan of Hans-Peter Feldmann, Joan Mitchell and Edwin Dickinson. Phillips says his influences come more from the traditions of literary fiction. In particular, he says the confessional poetry of writers like Robert Lowell, Elizabeth Bishop, Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath has had a huge impact on his work. “They made such beautiful prose out of their lives and I realized I could do that in painting,” he tells me.

In keeping with the efflorescence of cultural innovations during the 1950s and 1960s, the confessional poets discovered fresh territory to explore in their work by freeing themselves from the constraints of propriety that had governed poetic expression up to that time. Free verse went hand in hand with the revelation of personal intimacies that were sometimes considered shameful. Phillips likewise uses his work to intimate personal difficulties. They can be as commonplace as insomnia, in Twice a Day or Insomnia (2010), or as bleak as those suggested by Deadbeat Dad (2007), one of a series of works the artist has made of the back of a framed photograph—paintings that pack an emotional punch disproportionate to the bare facts of what they depict.

Phillips’s admiration for the work of the confessional poets is, like much else in his practice, a kind of throwback. Viewed in the light of today’s ultra-confessional culture, this connection suggests that Phillips has found a permission set by their example—permission for art to be the vehicle for the imparting of intimacies that gain a life beyond the moment.