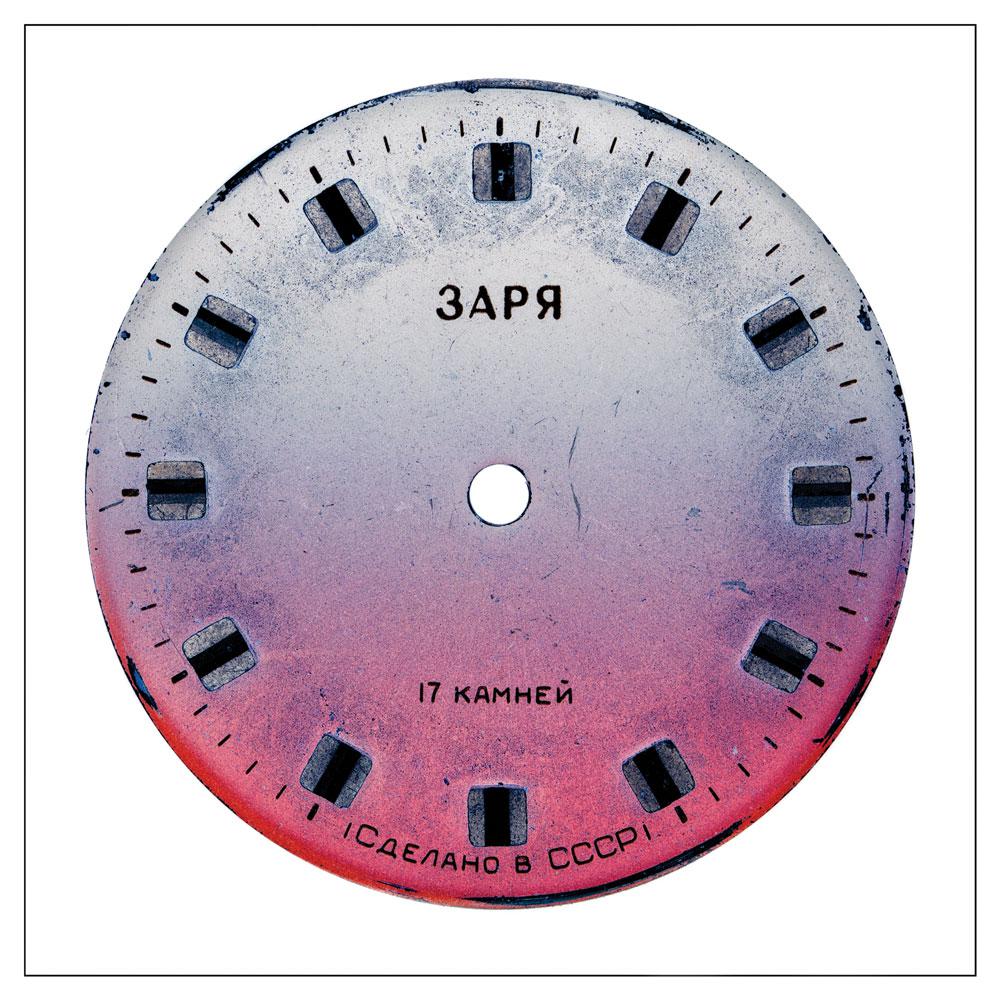

A large photograph of the moon hangs in the foyer of William Eakin’s Winnipeg studio. At least, it looks like the moon: a luminous, pockmarked orb, suspended in deep space. A closer view reveals that this glowing cosmic body is actually a greatly enlarged image of a scratched and faded watch face. It’s a Cold War–era, Soviet watch face, devoid of hands, stripped of function, speaking here to the phases of the moon, the passage of time, the vagaries of political ideology and our complicated fascination with modernist design. Time, design, ideology—these themes allude to the ways in which we attempt to make sense of our short little lives, set as they are against an incomprehensibly vast and oblivious universe. As with so many of Eakin’s photographs, this work also comments on the relentless way we manufacture and consume masses and yet more masses of objects, and then discard them, toss them into the dumpster at the back of the space-time continuum.

Eakin has built the latter stretch of his career on things he has retrieved from that dumpster—from thrift shops, junk stores, discount bins, gutters, campgrounds and, more recently, the low end of the online marketplace—and then reinvested with meaning. Just as he has been taking photographs since he was a child, he is a lifelong collector of the overlooked and underappreciated. Since the early 1980s, when he started staging and photographing miniature tableaux of little found objects amid the outsized flora of his backyard, these two compulsions have come together in his art. His camera imbues a range of seemingly inconsequential finds—rusty bottle caps, chipped enamel plates, broken souvenirs, defunct hockey coins, abandoned bowling trophies, streaked and damaged Polaroids—with humanity and pathos. He has also rescued from oblivion the unremarked vernacular and the seemingly kitsch, from astronaut figurines, gun-toting plastic cowboys and black-velvet bullfight paintings to homemade wooden plaques, Cultural Revolution–era Mao buttons and Niagara Falls cigarette lighters.

Despite initial appearances, the work is about neither nostalgia nor kitsch, both ideas being antithetical to Eakin’s ethos. His interest in revisiting objects manufactured during his childhood and youth—the economic boom time following the Second World War—is to recover something of their original intention while reinterpreting them as art. As for kitsch, the word connotes intellectual condescension and irony; what he values is the sincere sentiment that was originally attached to the things he photographs. For the past couple of decades, Eakin’s photographic practice has been largely a process of reclamation and animation, of transcending the found object’s “abjectness,” he says. His images both articulate a sense of loss and assert a declaration of renewed life.

Given the importance of discarded objects to his art-making, it is appropriate that both his studio and his dog were rescued from various degrees of anonymity and neglect. Eakin lives and works in a one-storey freestanding cinderblock structure, built in 1949 as a produce warehouse in an area of railroad tracks and offloading depots, now an impoverished neighbourhood of vacant lots, boarded-up corner grocers and despondent-looking social housing. He bought the small building—one of the last of its kind left standing in Winnipeg, he says—in 2009 and spent the next year putting together the means and the manpower to reclaim it and renovate its interior. Sleek and elegant as it now is, the place maintains many of its industrial features, including front and back loading docks and the heavy, wood-and-metal interior door to what was previously a walk-in cold-storage locker. “The bathroom,” he adds, “was the Tomato Room.” Make of that what you will.

Ben, a big amiable mutt with a broad head and mismatched ears, was a stray puppy found on a freezing January day two years ago. The artist found him, cold, starving and injured, on his front loading dock, searched fruitlessly for his owner, then adopted him. Limping but exuberant (one of his front legs is shorter than the other), Ben is a constant presence during our interviews, dropping his toys and then his food at Eakin’s feet as we talk, and clicking his claws on the bare floor as we sift through images, ideas, the meaning of collecting and the autobiographical impulse of photography.

“In art school, I learned that when you make a photograph, you make an image in reaction to yourself,” Eakin observes. “By extension, you have made a self-portrait.” Eakin’s photographs of cowboy toys, lamps and accessories designed for baby boomers, for instance, speak to the myths of heroism, masculinity and wild frontiers to be conquered by brave white men—myths that dominated the postwar years and shaped a generation’s early relationship to gender roles and cultural hegemony. “I reinvestigate received information, try to make sense of it,” he says simply, then names some of the TV westerns that enthralled him when he was young: The Lone Ranger, The Adventures of Rin Tin Tin, Zorro, Gunsmoke, Maverick, Bonanza and Rawhide. “As an adult, you find out that it was all manufactured in Los Angeles, that the machismo was not genuinely there.” Photographing cowboy paraphernalia enables him to analyze its original function and at the same time propose a newly illuminated place for it in the realm of visual culture.

“In the 1980s I started specifically building collections to photograph,” Eakin recalls, “but I’ve always liked having things around, so it was as much collecting colourful or interesting things as it was the justification or rationalization that I would use them in my work.” As a child, he gathered objects to him as a form of reassurance or emotional compensation. “It was a way of having some control over my situation,” he observes. “I wasn’t the happiest kid in the world.” Like many of his peers, the young Eakin would collect, say, comic books. Unlike the others, however, he would cut out the panels he liked, store them in envelopes, and rearrange them in ways more satisfying to his sense of narrative order or, perhaps, more consistent with his evolving aesthetic. Similarly, on family camping trips, he collected bottle caps and hammered them into stumps in designs that pleased him, niftily anticipating the intervention practices of postmodernism.

It’s not really a coincidence that decades later, in the early 2000s, he began making digital colour prints of old beer-bottle caps, enlarging them and isolating them on dark grounds so that they read like armorial crests emblazoned with names like “Lucky,” “Lemon” and “Up Town” or printed with images of bluebirds, maple leaves or sailboats. Eakin is interested in the way high-art traditions inevitably percolate down through popular culture to lodge in some mass-produced manifestation of low art. Still-life painting, his work tells us, has devolved into a photo-lithograph of garishly coloured flowers on the lid of a cookie tin, and landscape painting has become a snowy mountain top on a beer-bottle label or, yes, cap. While Eakin’s camera examines the nature-culture interface and deconstructs the postwar period in which the objects were made, it also creates a wonderful inversion. The decidedly low art he collects, even the negligible and ephemeral things that fail to register on the aesthetic spectrum, are reinvented in his photographs as high art.

And, again, as self-portrait. His lifelong sense of himself as an outsider, for instance, informed Have a Nice Day, his 1999 series of black-and-white photographs of alien figurines, toy flying saucers and UFO “sightings.” (He recorded donuts, pie plates and dog-food dishes as they flew through the air, pitched into orbit by friends.) “The alien presented as a site onto which we could project our anxieties and fears,” Eakin wrote in an exhibition catalogue at the time, before The X Files had been succeeded by The Vampire Diaries. “The idea of the alien comes and goes in the culture,” he says now. “It’s an area where people invest a misplaced sense of spirituality.” Shot with a range of cameras and in a variety of styles, from journalistic to hallucinatory, some of the Have a Nice Day source materials emit waves of evil and hostility; others, unfathomable mystery. Others still, especially the large-eyed, childlike figurines of extraterrestrials that Eakin photographed with a pinhole camera, exude vulnerability, pathos and an angelic sense of innocence. Misplaced spirituality.

A recent body of work, Fading Dream (2009–10), examines decayed and degraded Polaroids from the 1950s and ’60s; they’re drawn from a subset of the immense collection of anonymous and vernacular photographs Eakin has put together over the years. With subjects that range from freckle-faced children on mechanical horses to smooching couples to drunken partygoers, they again represent a time of social and economic optimism yet to be reiterated. They also represent a very particular photographic technology. In this series, Eakin focuses on messed-up versions of the peel-apart Polaroids produced with a camera and emulsion that were on the market from the late 1940s until the mid-1970s.

“It was a very unstable process unless it was coated, and sometimes people would choose not to coat the photos so they would discolour over time, or they would coat them in a way that left gestural marks,” he says. “I found myself collecting Polaroids that had this inherent mark-making or physical distress. It was a pictorial fingerprint that I chose to celebrate.” He adds that the early Polaroids “often reveal the physical circumstances in which the picture was made—heat or cold or inebriation.” Importantly, he also calls attention to the Polaroids’ objecthood, their concrete thingness. “I depict these prints not as dirty windows, not as looking through a marred glass at the past,” he explains. “I present them as objects with visible borders and casting shadows.”

The most striking work of the series, Fading Dream 122, reveals a bleached, spotted and smudged Polaroid of a New Year’s Eve reveller in a silly hat, blowing one of those unfurling paper party favours at an irritated cat. “It’s that moment in a party when things have gone a little soft and boredom’s starting to set in,” Eakin observes. “It’s a moment of pet torment, and it’s not just the guy teasing the cat, it’s the guy photographing the guy teasing the cat—that’s what you’re presented with here. And so you’re complicit in this image.”

Appropriation is clearly a part of Eakin’s practice, but in a sense he inverts its more common deployment. Where Sherrie Levine challenged ideas of authorship, authenticity and originality by reproducing the famous images of a famous photographer, Eakin recovers photos and objects from conditions of anonymity and discontinuity. “It’s a mild tragedy that these images have lost their connection with their originators,” he says of the Polaroids he has collected. “The sense of family or community that’s depicted has been ruptured.” He believes, however, that he is undertaking a rescue, taking ownership of the image, the object, the method and the event that time had already severed from use and place. He revivifies these flat and blotchy objects, reanimates them and bestows on them a new and fond regard.

The light outside the studio is fading as we look at Eakin’s series of cosmic watch faces. Titled 24Hours (2012), the work originated in his long-standing interest in modernist design, again as it reflects the optimism of the postwar age, and in his specific curiosity about the ways in which industrial designers in the Soviet Union navigated around the propagandistic, social-realist art of their time and place. Rather than fixing upon the “asymmetrical, amoeboid and flamboyant” watch designs that had originally drawn him to these artifacts, however, Eakin began to explore and digitally manipulate the way time and wear were etched on the more conventional circular watch faces in a manner that suggested astral bodies. “The justification of the image has been realized as something quite separate from the existence of the watch face,” he says. One object suggested a sun with a fiery aura, another, a starry night sky, and yet another, a gorgeous sunset or sunrise, a twilight period of transition. All Eakin’s images evoke ways in which human beings attempt to track and measure our time on Earth against the evidence of the infinite and, well, having travelled this Möbius strip, we’re back at the beginning again.

A large photograph of the moon hangs in the foyer of William Eakin’s Winnipeg studio. At least, it looks like the moon…

This is an article from the Winter 2013 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.