Everything kicks hard against the shore, sending up big smacks of foam—here is majesty, isolation, a cold void; sparkling, ceaseless commotion, landscape gouged and scratched. The cliffs are Gothic; ocean-clawed and vertiginously high—though rogue waves have, upon occasion, crept up the cliffs and swept unsuspecting tourists to their deaths. Cape Spear, Newfoundland, is the easternmost point on the North American continent, the closest one can come to Europe without getting wet. It is also the setting for a performance piece by Will Gill that is named after the site.

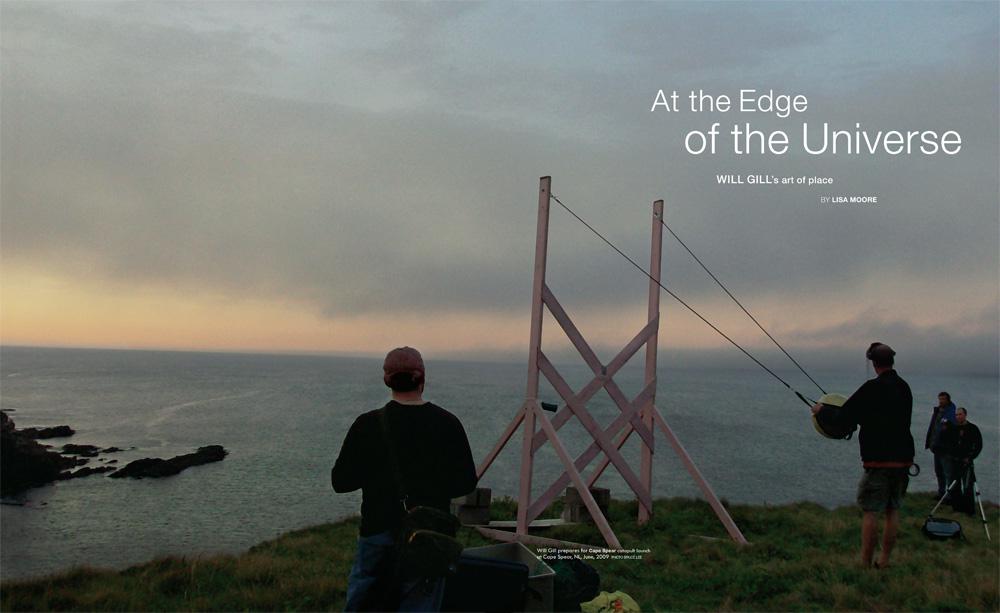

Imagine an evening: twilight settles and a gathering appears in silhouette along the top of the cliff—a troupe of revellers and artists. They gather around the base of a tall wooden structure that happens to be a catapult. The crew load up the giant slingshot and let fly. A glowing red sphere sails over the cliff and down into the water below.

It is swallowed by waves, then emerges, still burning. It bobs and dips, is drawn out by the surf and slides back toward the shore. The fluorescent orange of the fibreglass-encased flare glows eerily. More spheres are catapulted; they float toward each other and apart.

Some contrasts, paradoxes and recurring themes that animate Will Gill’s performance Cape Spear, and the video that documents it: the juxtaposition of the elements of water and fire, an uncanny coupling because the glowing, ember-like spheres are engulfed by waves but are not immediately extinguished.

The juxtaposition of light and darkness—the flares burn for just 15 minutes. The brevity of the event becomes part of its content, the lifespan of a burning object, the notion of duration. Gill’s video is just over three minutes long, but it represents, thanks to time-lapse techniques, a much longer period; the diminishing dusk turning to inky darkness. “I liked the idea of melding opposites,” Gill told me. “Hot and cold, light and dark, fast and slow. I didn’t know exactly what I wanted but knew I wanted to make sculpture kinetic, work with light and document it.”

I met with Gill at the Duke of Duckworth pub late one snowy February afternoon to talk about Cape Spear. I watched the video on his laptop while hockey played on screens hanging from the ceiling. The bar was noisy and Gill’s video was full of the graceful sway of the spheres cradled in the rough waves, otherworldly and coy about the treachery of the sea.

We spent a couple of hours talking about Gill’s paintings, photographs, sculptures and video art. We talked about how one’s environment informs the media an artist chooses, Gill’s love of exploring new materials, a sunken bathtub, the properties of fibreglass, the rules of boat-building, that particular bluish-green you can see on the odd house in some communities around the bay (we surmised that there once must have been a sale on that particular tint). We talked about the difference between painting and making sculpture, the demands and joys of both, the act of dreaming and its necessity to creativity, visual puns, the dramatic beauty of Newfoundland and what it’s like to live and make art at the edge of the universe.

It was easy to believe, with the wind howling outside and the snow hissing around the street lights in the alley that leads to the Duke, that we were at the edge of the universe. Or at least in a slightly out-of-the-way corner of it, difficult to get to: a great place to find oneself.

Gill had arrived at the bar from The Rooms, which houses Newfoundland’s art gallery and archives, and where he works as an installation technician. He was on his way home to his wife, the artist Anita Singh, and the couple’s four-year-old son, Niko.

Originally from Ottawa, Gill wound up in Newfoundland when he was given the opportunity to apprentice in a bronze-casting foundry with the Bulgaria-born Newfoundland artist Luben Boykov. Like so many writers, poets, visual artists and musicians, Gill fell in love with the place and stayed.

I wondered if the embers in the Cape Spear performance were a metaphor for the life of a Newfoundland artist, someone floating at the periphery of the major art centres in this country. “For me, Cape Spear was always about struggle and isolation,” says Gill. “There is something incredibly stark and lonely about the sea. Its vastness is a force on its own, but then add its unpredictability and its relentless, driving rhythm, and one is faced with an awe-inspiring, sometimes terrifying life force. I wanted to introduce a series of sculptures into this unpredictable situation to see what would happen.”

The piece also attests to the magnificent scale of the ocean, contrasting it with the ephemeral and insubstantial—small sparks against a vast, black canvas of sky and water. The idea for Cape Spear came to Gill during a bonfire at Outer Cove Beach. I asked him how the landscape informed this work. “Two simple things,” Gill said. “I was throwing a burning log from the fire on the beach, at night, into the ocean, watching its trajectory. And I was also watching bits of ice from an iceberg slowly float ashore.”

Eventually, the spheres in the video drift away from one another and are extinguished. There is the idea of impermanence and a kind of yelling-out in protest against it. Human scale—our smallness in time and space—is part of the subject matter.

“I began to see a very simple narrative emerge with respect to life’s struggles and, in some ways, aspects of life on an island,” said Gill. “The glowing spheres start off bright, full of life, assertive. There are moments when the forms relate to one another; they almost dance. Then the struggle against darkness and the turmoil of the storm. They separate and are isolated, fighting for survival. Confidence erodes. Their light dims as the struggle finally begins to take its toll. They unite again, as a group, after washing up on shore. Spent. Struggle, a sense of isolation and community are potent aspects of life on an island. Life and death seem somehow closer to the surface.”

Gill plays with absurdity throughout his work, which is permeated by crackerjack logic and craftsmanship as well as a comic sensibility. There is a wackiness that is manifested through visual puns and an unexpected use of industrial materials, which Gill makes poetic, aesthetically seductive.

Hurling embers into the night sky from the edge of a cliff is an example of this ramped-up absurdity, as is Gill’s construction of an anachronistic weapon—the catapult—to do it. Weapons show up throughout Gill’s work, their suggested violence often camouflaged, especially in his paintings, by bright candy colours or feminine pastels. The catapult here acts as a kind of maypole, the focal point for the revelry. And though it is not a weapon, it serves a real purpose. “The slingshot was a combination of play and necessity,” said Gill. “The spheres themselves weighed several pounds each, so throwing them by hand would not have gotten them any distance, let alone to the middle of a cove 200 feet away. The slingshot was also crucial in keeping me and my helpers away from the treacherous Cape Spear shoreline.”

Proximity to nature is also important to many artists working in Newfoundland. “Being right next to the ocean is a gift—it’s hard to ignore, no matter what discipline you’re working in,” said Gill. But Gill’s nature is not the pristine, untouched North of the Group of Seven, Northrop Frye or Margaret Atwood’s Survival; rather it is manhandled, modelled, abstract and full of traces of industry. His work often incorporates or brings to mind the tools and equipment that accompany a life spent on the sea: marine paint shades, hazard-sign ambers and oranges, fibreglass, bits of debris found on the ocean floor, flares and barnacles.

In this way his work bears a resemblance to that of the late Don Wright—the come-from-away Newfoundland artist who in 1985 created an infamous work called Red Trench by using fibreglass to cast trenches in the sand, incorporating bits of flotsam found on the beach.

“I began by trying to make industrial-looking objects from natural materials,” said Gill when I asked him about the media he favours. “Now I find myself more and more drawn to making organic-looking objects with man-made materials. I love finding out about materials and their properties and marrying them with a given piece’s aesthetic concerns.”

Cape Spear’s spheres illustrate this perfectly. “I needed something that was extremely strong, strong enough to withstand a tremendous impact with the water as well as the thrashing the spheres would take when coming ashore against the rocks. The material also needed to be translucent so as to produce an even glow when chemical light sticks were placed inside. The answer was simply to use the same technology as boat-builders use: fibreglass and epoxy resin. It’s strong and waterproof.”

Gill has a wanton curiosity about how things work, a desire to push materials—fibreglass, bronze, wood—so that they behave out of character, bend over backwards or morph unexpectedly to support his vision. He seems to enjoy mastering the conundrums of craft and his work is informed by these explorations. Or perhaps it’s the other way around—he’s gripped by an emotion, an image or a concept, then searches for the right materials with which to render it.

Painting is relatively new for Gill: his painting subjects include guns, saw blades, searchlights, skunks, copulating dogs and rabbits, bubble-gum dispensers, missiles, picket fences, industrial piping and birds. His surfaces are worked: scratched, splashed, smeared and roughed up. The shapes are strong and simple, bold and bright.

“I don’t like the word whimsical,” Gill says. And though there is a playfulness to Gill’s subject matter, a toying with viewers’ preconceptions, a kind of child-wildness, there is also a palpable anxiety at the surface of each painting—and an underlying complexity, an exploration of violence, impermanence and lost innocence, with the flatness of language thrown into relief by a stencilled word here and there.

Bareneed, another Gill installation, also concerns mortality, solitude, human scale, absurdity, humour and the ocean: the work is a replica of an old-fashioned cast-iron bathtub that Gill saw on the bottom of the ocean while sea kayaking in the community of Bareneed. Gill floated over the abandoned tub, which was sunk several metres below the surface not far from shore. “The white enamel looked ghostly and was a haunting image for me,” Gill said. The bathtub appeared casket-like, wedged as it was among boulders and green murk, rusted-out barrels and car parts, fish and the wobble and weave of light and shadow.

Verisimilitude was important to Gill in constructing the replica, which resembles a real tub in every respect except its weight. Gill also made casts of barnacles that he found along the shore and attached these replicas to the tub on its inner and outer surfaces. They elegantly make reference to the notion that the tub has been submerged in the sea. The irony is clever and also jarring: the tub surrounded by water rather than simply a vessel for it.

Gill has turned the thingness of the tub inside out. It comes to suggest the very stripping-away of purpose, a morphing from one kind of object into another. The sculpture is subtle. It is a piece about dumping and divesting, ablution, absolution, a kind of forgetting or sloughing-off of context: a study of the persistence of objects and how objects resist meaning; notions of the familiar made unfamiliar and eerie.

Gill’s rendering suggests domesticity and alludes to the history of resettlement in Newfoundland. Between the 1950s and the 1970s, whole communities were abandoned as the rural population relocated to urban centres for employment opportunities. Houses, churches, schools and graveyards were left to crumble into the earth. Bareneed is in part about place: the reasons that people leave; the reasons they stay.

At the Duke, Gill and I discussed the pros and cons of living so far from art centres such as Toronto and Vancouver. We talked about the difficulty of touring work that is not easily portable and what these things mean in terms of audience and the growing population of artists here.

I know the tremendous advantages that come with living in a close-knit arts community like St. John’s. There’s the exciting habit of talking about ideas and projects in bars and at book launches, openings and parties. There’s a lot of collaboration across disciplines—visual artists work with playwrights and actors on set designs, poets and musicians pair up, novelists and filmmakers join forces. The result is an exciting crossbreeding of ideas and aesthetics, with each discipline enriching the others.

The problems arise when it comes to getting national and international attention for visual art, especially for emerging artists. There’s a dearth of national critical attention for visual art from the Atlantic provinces. It’s difficult and expensive to transport work off the island, and it’s also expensive for critics to come so far east to see what’s happening here: and when it comes to visual art, nothing quite compares to being in the presence of an actual work. As Gill puts it, “When you’re in front of a work of art you can feel it, see it and smell it. You can’t get the same sense of scale from a picture—how it relates to the human form and how you will ultimately engage with the work.”

But he is also keenly aware of the advantages of working where he does. “There’s a real freedom here,” he says. “I find artists feed off of one another’s energy in a very positive way. Families are important everywhere, of course, but I’m talking about a kind of communal family. In larger urban centres there’s a feeling of alienation and loneliness for a lot of people—it’s so easy to feel like you belong here. My son is growing up here and it feels like he is part of a great big family.”

Gill closed his laptop and we headed out into the snow. On Duckworth Street the cars were already covered with a fluffy layer of white. He offered to drive me home; I was more or less on his way. I glanced across the city toward Signal Hill, the tower where in 1901 Marconi received the first transatlantic wireless transmission. The rest of the world did not seem that far away.

This is a feature article from the Fall 2010 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.