In the standard history of contemporary Canadian art, there is perhaps no chapter as essential or enigmatic as the legacy of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. It’s a tale that has been so often told and retold in the years since the school’s heyday in the late 1960s and 1970s, a narrative of a small experimental art college populated by many of the defining figures of the era—Lawrence Weiner, Dan Graham, Robert Barry, Sol LeWitt, Joseph Beuys, Daniel Buren, Seth Seigelaub, Victor Burgin, Lucy Lippard, Miriam Schapiro, Robert Smithson, Gerhard Richter, and the list goes on—that little question remains as to the model role that NSCAD played not only in the dematerialization of artmaking, but also in the de-institutionalization of art education. In short, when it comes to radical pedagogies and Conceptual art, NSCAD is legendary.

Yet thinking about the NSCAD legend at a distance of some four decades, and having lived in Halifax myself in the mid-1990s amid the still resonant echoes of that era, interesting questions remain. What were the specific conditions that allowed for an art school to be reimagined from the ground up? What exactly was it that drew that itinerant marquee cast of American and European (and let’s not forget, Canadian) artists and teachers to a previously unknown provincial art college in the conservative hinterland of Nova Scotia? Why Halifax, and why then?

It’s all quite simple, and a bit coincidental, according to Garry Neill Kennedy—and he should know. Just out of grad school at Ohio University and 32 years old, Kennedy was named the president of the then Nova Scotia College of Art in June 1967. Starting the next year, and with the help of key new faculty members and fellow artists like Gerald Ferguson and David Askevold, Kennedy radically transformed what had been a sleepy outpost of traditional art instruction located in an old church hall into an international hub of the conceptual avant garde. In 1969, the school was renamed the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, and soon after moved to the Morse’s Tea Building on the Halifax harbourfront. Kennedy stayed on as president until 1990.

“We used to talk in grad school about how the art schools were terrible, so incredibly bureaucratic, and how to make a good one,” Kennedy explained recently by telephone from Halifax at the opening of the survey exhibition “The Last Art College: The Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1968–78” at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia. “I think we were able to do that here because we came first and foremost as active artists—I still am one. And I was teaching. Presidents didn’t teach then, and they don’t teach now. It’s maybe even worse now, even more bureaucratic, all ‘roles and goals.’”

Along with taking an active place in the classroom and studios, Kennedy and his colleagues almost immediately took unprecedented steps to deconstruct, then reassemble, the college’s bureaucratic framework.

“One thing we didn’t do right away is we didn’t give grades. We instituted a pass/fail system, which was revolutionary at that time,” Kennedy says. “We were also 25 years ahead of most art colleges in Canada in giving degrees. The college was so infatuated with the Ontario College of Art model that it didn’t give full degrees, it was being held back. I was a graduate of OCA, so I knew it wasn’t that great. I looked at the school’s charter and low and behold it gave us permission to hand out degrees. So we gave the BFA and then the MFA.”

It wasn’t an easy transition, though. Kennedy almost immediately laid off old-school faculty (“I still remember that board meeting. There were all kinds of phone calls and serious protests, students out in the streets, et cetera.”) and the school took on the role of a kind of rogue agent, introducing minimalist and conceptual thinking, which Kennedy and his fellow artist/teachers brought with them from New York and the American midwest, to Halifax’s otherwise staid art scene. (“We battled with the old guard. There was no Modernist precedent, no Jock MacDonald, who was my teacher, no avant-garde practice in the city, let alone on the faculty. These people didn’t exist. So we just started in with this post-Duchampian stuff.”)

At the same time, monumental shifts were underway elsewhere. Political unrest, the global counterculture and, in particular, opposition to the Vietnam War were pushing artists and students to seek out not only radical alternatives to status quo thinking—Kennedy points to CalArts and Rochdale College in Toronto as other good examples—but also a safe haven from the threat of being drafted or otherwise ideologically marginalized. For many, NSCAD made the perfect redoubt.

Geography played a role, too. The contemporary art scene was becoming ever more mobile and international, with Halifax, as it turns out, a convenient way station on the transatlantic route between New York and Europe. (Robert Frank, June Leaf, Philip Glass, Joan Jonas and Richard Serra are just a few of the artists whose early connections to NSCAD led to continued ties to the province in and around Cape Breton.) NSCAD “rode a wave of Conceptual art, but that was coincidental,” says Kennedy.

“There wasn’t any money in art and these artists [who found their way to Halifax via New York or Europe] weren’t famous then. Gerhard Richter had a show here and his paintings sold for $1,000! Still, nobody could afford them. I think the idea of artists wanting to do something is what was important. They wanted to make a print, a book, an exhibition…they wanted to do something. That’s the key idea about the institution…I mean there are visiting artists and they come and they give their talks and then they disappear. But we kept them around for a while, and gave them real opportunities to do things they were interested in. They weren’t visiting artists as much as they were doers.”

It’s an interesting thought that in many respects brings the NSCAD legacy forward into the present. In that unfolding collision of radical social flux and auspicious circumstance, NSCAD and Halifax became a kind of transitory nexus for the leading edge of contemporary art. Artists, thinkers and students came and went, experimented with work and left their mark in building a critical conceptual mass that, despite its relatively remote and somewhat unexpected location, stands as the antithesis of isolated. That’s not so different than, for instance, the roving geopolitical concerns of the current art world, especially in major international exhibitions such as Documenta, which have made determined efforts of late to establish periphery locations across the globe (in Banff, Cairo and Kabul for Documenta 13 in 2012, and in Athens for the upcoming Documenta 14 in 2017) as laboratories for non-conventional thinking, engagement and artmaking. You might even go so far as to say that NSCAD was a prototype for this kind of free-form pan-national art network.

Kennedy and company’s “anything goes” invitation to teaching and making art made all of that experimental synergy possible. As he puts it: “Whatever we wished for, we did it. It was based a lot on trust. People did good things, but risky things. They all worked, in my view.” Considering the ever more perilous state of art education (NSCAD included), and higher education in general, thinking about the NSCAD legacy (or legend)—how it happened, why it happened and where it happened—seems as crucial now as ever, even if as a utopian moment long past that remains critically relevant in any discussion of what our institutions and expectations can and should be in the years to come.

“It’s history, that’s how I look at it, an important history,” says Kennedy. “But what it shows is that making change and taking risks does work. It’s proven to work.”

4 Key Artworks That Made NSCAD Legendary

“The Last Art College: Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1968–78” at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia features more than 100 objects of various media created as a direct result of an involvement with the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design during this formative era. With more than 60 artists represented in this exhibition, there are many examples that resonate with significance. Here are four that stand out for exhibition curator David Diviney, along with his thoughts on them.

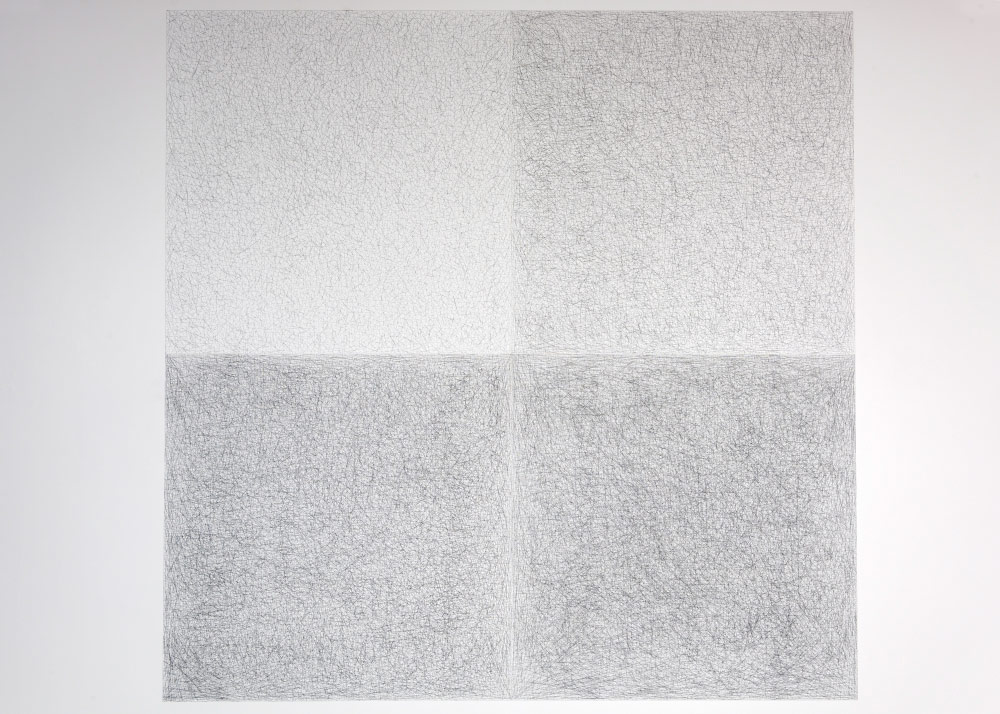

Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #196: A square divided horizontally and vertically into four equal parts, with progressively longer lines (3”, 6”, 9”, 12”) in each quarter. All lines straight and drawn at random (1972)

“This work—along with Lewitt’s Wall Drawing #129: Ten thousand straight lines 1” (2.5 cm) long, uniformly dispersed over the wall (1972)—really stands out,” Diviney states. “They were first installed at the college outside of Garry Neill Kennedy’s office at the time and drawn by Hazel Boudreau, a NSCAD student from Church Point, Nova Scotia, following LeWitt’s instructions in the titles of the works themselves. These works make visible the experimental impulses of the period and reveal aspects of the pedagogy at play in this sort of exchange or collaboration between artists and students. It is a real coup to have the Wall Drawings back in Halifax for the first time in over 40 years. Who knows when they’ll be seen again.”

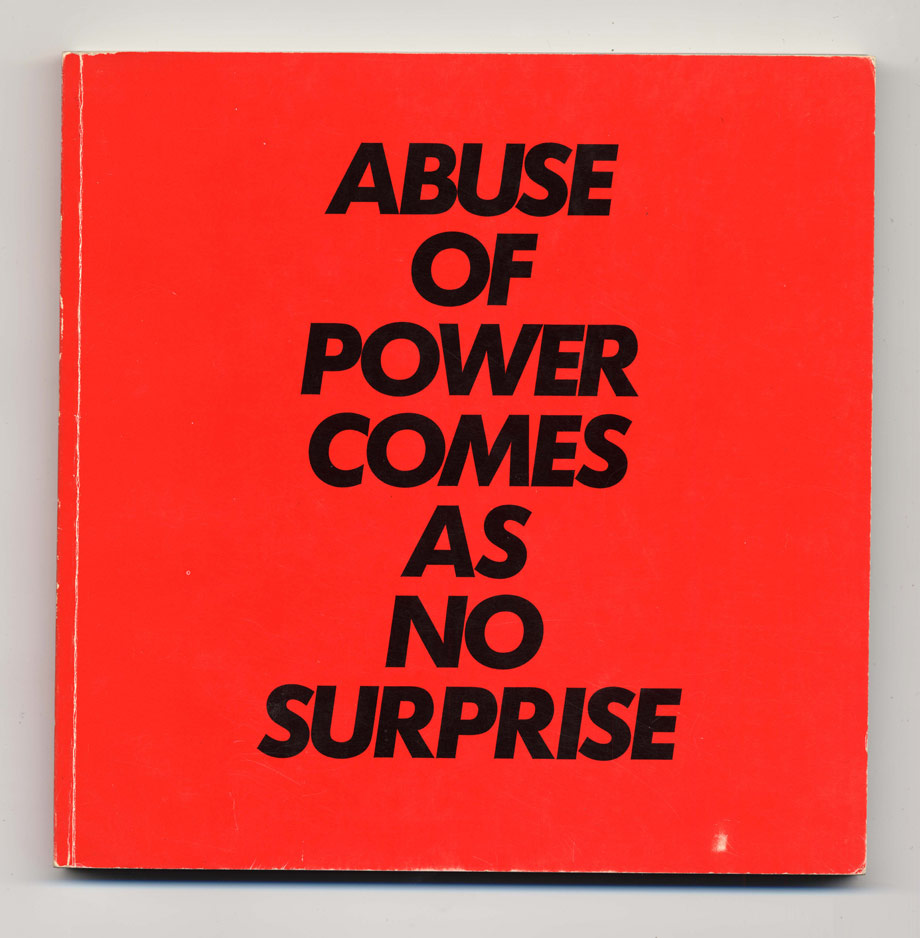

Jenny Holzer’s Truisms and Essays (1983)

“Between 1972 and 1987 the NSCAD Press published 26 titles by such artists as Yvonne Rainer, Dara Birnbaum, Dan Graham, Michael Snow, Claes Oldenberg, Daniel Buren, Donald Judd, Michael Asher and Marta Rosler, to name some,” Diviney notes. “Jenny Holzer’s 1983 Truisms and Essays exemplifies the potential of the book form as an art object like few others. From its cover with the bold black type upon red ground—ABUSE OF POWER COMES AS NO SURPRISE—to the pages in between, Holzer’s running list of one-line provocations implicates the reader as an active participant in her work. We’re asked to determine the veracity of what is being stated here and, more broadly, urged to do the same out there in the world around us. This is a powerful and important book. It is still very relevant today.”

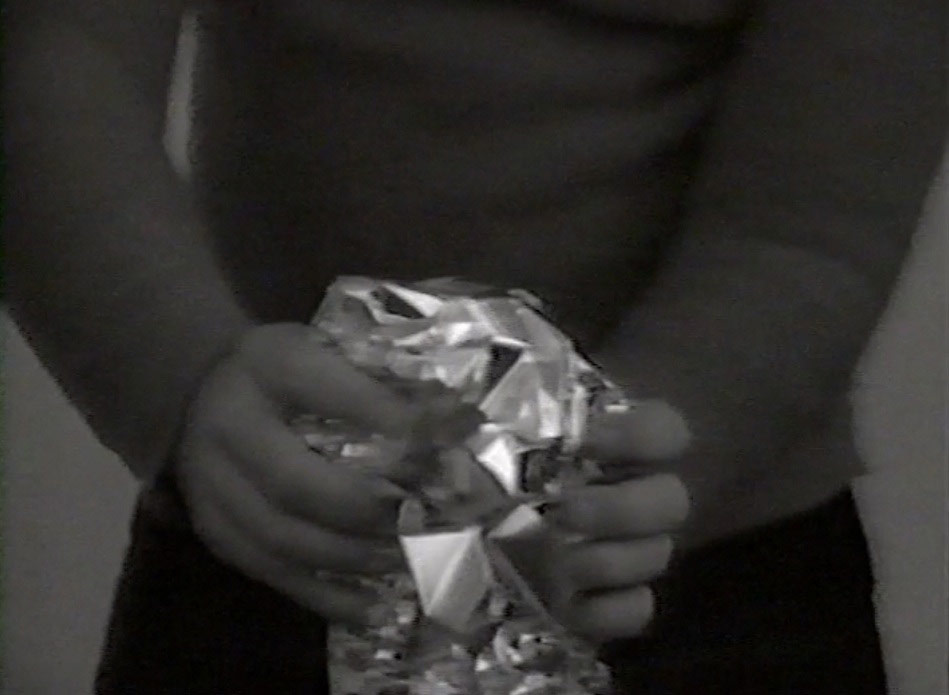

David Askevold’s Fill (1970)

“David Askevold was one of the most important contributors to the development and pedagogy of Conceptual art. His pioneering films and videos from the late 1960s and early 1970s were some of the earliest of the genre,” Diviney explains. “Fill (1970) is a black-and-white video of his that runs eight minutes 20 seconds. Here, Askevold treats the monitor as a picture/sound box. In a performative gesture, the artist fills the screen by wrapping one sheet of aluminum foil after the next over a live microphone. Once filled, he reverses the process, removing the sheets one at a time until just the microphone is in the frame. The audio implodes during the wrapping and explodes as the sheets are pulled away. Fill stands as Askevold’s very first video. It is a Canadian classic.”

Mario Garcia Torres, What Happens in Halifax Stays in Halifax (in 36 Slides) (2005)

“This is the most recent work included in the exhibition. While the making of this video steps outside of the 1968–1978 parameters of the show’s subtitle, it exactly that time frame which is the object of this work’s focus. It takes a starting point Robert Barry’s submission to David Askevold’s Projects class where the artist’s faxed proposal requested that the students should ‘gather together in a group and decide on a single common idea.” Within this, the work would only exist as long as it remained a secret among the students,” Diviney notes. “Intrigued by the incomplete nature of this storyline, the artist’s research culminated in a class reunion held in Halifax in fall of 2005. What Happens in Halifax Stays in Halifax (in 36 Slides) is comprised of still frames, each with text juxtaposed against imagery of people—former students and Askevold himself—and sites related to the Barry project. As Garcia Torres states in The Last Art College book, ‘…it seems that the secret in itself is the most insignificant part of the story for those involved in the class, as one discovers that an examination of their own memory in order to reconfigure what happened those days becomes the central element of the narrative.’”

All photographs in this post are by Steve Farmer and are courtesy of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

“The Last Art College: The Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1968–78” continues until April 3 at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

Gerald Ferguson's Choral Reading of The Standard Corpus of Present Day English Language Usage Arranged By Word Length in 20 units for a chorus of 26 voices (1972/2016) is one of many works that came out of NSCAD's unique approach and legacy.

Image courtesy of the estate of the artist.

Gerald Ferguson's Choral Reading of The Standard Corpus of Present Day English Language Usage Arranged By Word Length in 20 units for a chorus of 26 voices (1972/2016) is one of many works that came out of NSCAD's unique approach and legacy.

Image courtesy of the estate of the artist.