Land, Spirit, Power: First Nations at the National Gallery of Canada was mounted last fall at an extraordinary time in the struggle of First Nations peoples for recognition of their rights and title to their land. Part of that struggle has been for access to the cultural institutions of Canada where, as in the case of this exhibition at the National Gallery, non-native Canadians might begin to question the various fictions most of us hold about native people.

The exhibition catalogue went to press in the summer of 1992, when post-Meech constitutional talks—talks which included First Nations representatives—were underway. In her essay, National Gallery curator Diana Nemiroff drew an analogy between these negotiations and the occasion of the exhibition. She wrote, unfortunately too optimistically: “Aboriginal issues, in particular the inherent right to self-government, are a central part of the discussions and are being formally recognized for the first time. This has come about as a result of the insistence of native leaders themselves that their voice and concerns be heard in the forums that count. By analogy, the belated recognition now being given contemporary native art is the result of a similarly favourable conjuncture of circumstances.” Those circumstances include lobbying by native artists themselves, especially the Society of Canadian Artists of Native Ancestry (SCANA). They also include recent shifts in how historians, critics and curators deal with culture and art. The challenge to the monolithic, European-based version of history now cuts across whole fields of inquiry into culture. The way history is written can be a powerful instrument by which one group may dominate or even obliterate each another. Thus the debate about whose version is being staged, or whose voice is being heard, has a highly political character.

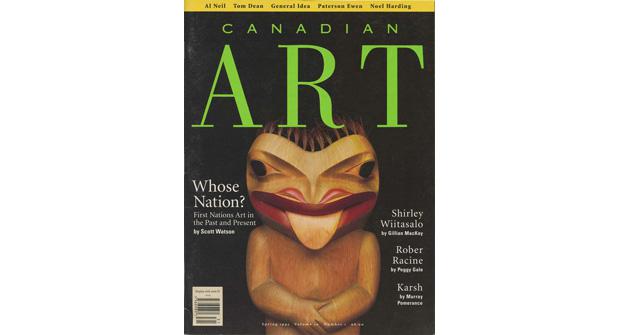

So begins our Spring 1993 cover story. To keep reading, view a PDF of the entire article.