On the same night that Taika Waititi dedicated his Academy Award for best adapted screenplay to “all the Indigenous kids in the world who want to do art and dance and write stories,” community members at the Port of Vancouver blockade, at the intersection of Hastings and Clark streets, were preparing for arrests. During the occupation, artists such as Justin Ducharme and jaye simpson, poets such as Brandi Bird, Billy-Ray Belcourt, Samantha Nock and Jessica Johns, and academics such as Dallas Hunt spent time at the site, holding the space. The following morning, the last Elder would be forcibly removed from the fire at the centre of Clark and Hastings and arrested following an injunction issued by the BC Supreme Court.

With his land acknowledgement and his assertion that “we are the original storytellers,” Waititi reminded audiences around the world that, for Indigenous peoples, art should be deeply tied to political life and the sovereignty of Indigenous communities. Waititi was also describing the multitude of roles and practices that can comprise “art.” His statement was a reminder that Indigenous art made for and consumed primarily by non-Indigenous audiences is just another facet of the cannibalizing of culture and that, for Indigenous peoples, our art is defined by its active and non-performative connections to the political lives of our communities. In other words, it optimistically assumed that if non-Indigenous people consume our art, they must also care about our resistance.

Many articles have summarized the political dynamics of what is happening in Wet’suwet’en territory and across Turtle Island, including those shared by the network of Indigenous creative communities mobilized by the hashtag #ShutDownCanada—a call to action that spread across social media when the RCMP began to raid Wet’suwet’en territory and arrest community members; Cree-Métis writer Samantha Nock has compiled a detailed resource list. I’m not going to offer another summary of what has happened, but rather focus on some of the Indigenous youth artists and writers who are putting their bodies on the line, many of whom are queer, trans and Two-Spirit youth and whose identities and roles are often abstracted in online rhetoric and media about Wet’suwet’en.

At a water ceremony hosted on Garden River First Nation by the community and the Onaman Collective (Christi Belcourt, Isaac Murdoch and Erin Konsmo), I learned that Indigenous queer, trans and Two-Spirit folks across generations have often been the ones leading actions for their sovereignty and land protection against militarized police forces. But when Indigenous youth engage in land-defence work, they find that portions of their identities are erased in the shadow of public discourse, especially when the sole focus is on their experiences as Indigenous peoples within narratives of reconciliation. Billy-Ray Belcourt wrote on Twitter, in the days following the rallies for Wet’suwet’en: “btw at the blockade at Hastings and Clark last night someone drove by and yelled ‘fucking f*ggots’ if anyone needed more evidence of the way colonial power knots all other forms of oppression together.”

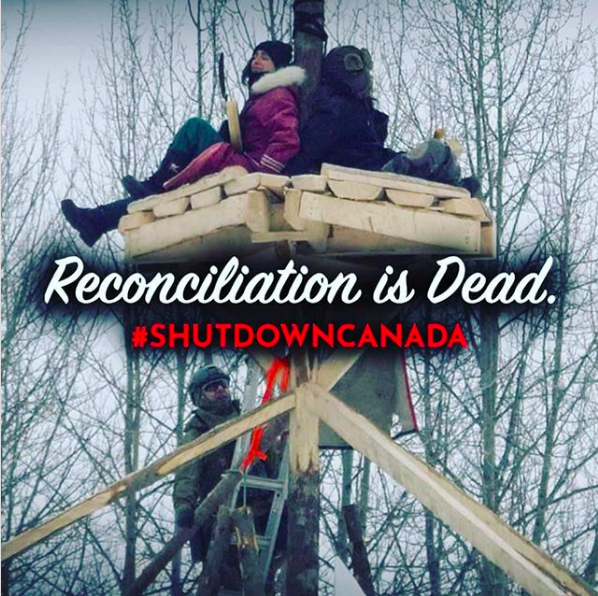

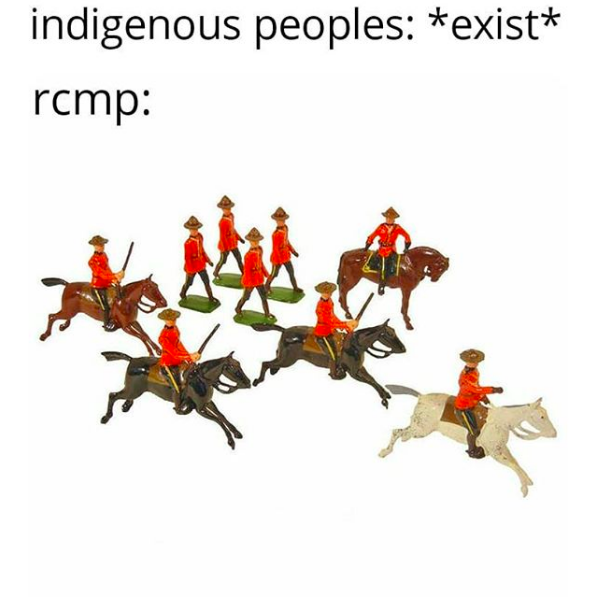

Meme from the @decolonizemyself Instagram, posted February 8.

Meme from the @decolonizemyself Instagram, posted February 8.

Youth artists are leading and organizing actions for Wet’suwet’en in Vancouver, in Wet’suwet’en territory and across Turtle Island. Last week, the kinship collective occupied the Museum of Modern Art in New York in support of Wet’suwet’en. The Mohawk community from Kahnawá:ke began a train blockade last week that shut down Via Rail and inspired railway blockades across Canada. There have been recent actions in Montreal and Toronto led by Indigenous community members. And last week some 20 Indigenous youth occupied Minister of Crown–Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Carolyn Bennett’s office in Toronto.

When I asked Oji-Cree Saulteaux poet and performance artist jaye simpson about Indigenous youth-led resistance for Wet’suwet’en, they had a great deal to say: “We shut down the BC Legislative Assembly building for about four or five hours [in response to the RCMP raids at the Unist’ot’en community village and Wet’suwet’en territory]…that’s making history. This shows that youth are very powerful. And so my hope is that more people begin to listen to these young folks. There were so many youth, so many who had been there for 120 hours: pushing long and hard. And it was raining and cold for a lot of it. They had a ceremonial fire. They had great teachings. They followed the protocols and it spoke to what inter-nation solidarity could look like.”

But simpson said there are real risks: “The scariest thing was how the media were treating a lot of folks; a lot of them were antagonizing the media liaisons and [those] assigned to talk to cops. There were people who were there to instigate and escalate. At one point I had to do some de-escalation [with a white woman in the crowd]. When we look at who is putting their bodies on the line and who is taking that risk, it’s Black and Indigenous youth. There was such a presence of Black and Indigenous youth at the legislature building. The amount of Two-Spirit, queer, Indigiqueer and trans youth was so beautiful.”

Carrier Wit’at multidisciplinary artist and curator Whess Harman also reflected that there were a great deal of Indigenous queer, trans and Two-Spirit youth mobilizing for Wet’suwet’en, so I asked them why they think there are so many queer artists on the front lines of manifestations, occupations, protest art and public discourse generally. “It has very visibly been younger, Two-Spirit, queer Indigenous artists and writers [present at the sites],” said Harman. “I think part of that is we feel a real kinship with each other and that’s drawing one another out, and we feel very protective of one another. A lot of us are willing to be arrested, but we are trying to do that in a strategic and impactful way.”

Harman also discussed the love emanating throughout the protest sites, despite Indigenous youth being faced with militarized violence. “I’ve never been so well-fed at a protest,” said Harman. “I’ve loved all of the community support and making sure we’re watching out for one another. There’s so much work happening behind the scenes…all of that work is very, very appreciated on the ground. I don’t know what to say other than that I’m extremely grateful, especially as someone from a Northern community. From having lived on Wet’suwet’en territory for so much of my own life, it’s been really meaningful to have a community come and gather. [The Clark and Hastings site] feels like home.”

Meme from the @skodenne Instagram, posted February 10.

Meme from the @skodenne Instagram, posted February 10.

What Harman is naming here is kinship, a drive to fiercely protect one another, rather than use individual ideas, institutions and subject positions against each other. For an emerging Indigenous queer futures movement, kinship isn’t a metaphor (to paraphrase Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang’s seminal 2012 paper “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor”). Kinship starts with how we frame every facet of our thoughts, actions, intentions and relations with all Creation, as the Indigenous youth protesting on behalf of Wet’suwet’en argue. This is perhaps the most misunderstood facet of this movement: that the queer futures movement is attempting to acquire and protect scarce institutional resources. Indigenous youth out for Wet’suwet’en aren’t even contending with an institutional model and view their work as existing outside of and refusing forms of institutionalization.

Anne Spice, an Indigenous queer writer and academic and ongoing defender of Wet’suwet’en even before the rallies, was arrested by RCMP at Unist’ot’en camp. Images of Spice’s arrest spread across social media with the words “Reconciliation is Dead” superimposed over top, and it quickly came to define the raids on Unist’ot’en camp. When I asked what drew them to land defence, Spice replied: “Part of it was this really incredible community of queer, Two-Spirit people and trans people out on the front lines. I’ve been doing this work, especially over the past five years, and it’s a clear pattern. These are people who are really willing to put themselves on the line and keep showing up again and again. Queer Indigenous people are in a particularly good position to really understand what it means to remake relations with the land and with the animals and all of the non-human beings that we are connected to. There’s something about both Indigenous and queer life that is constantly looking outside of the heteropatriarchal colonial norm for more just and healthy relations. And since we’re already doing that work, there’s a really powerful connection to land-defence movements.”

For simpson and for Spice, the Indigenous queer futures movement taking form at rallies for Wet’suwet’en is asking what happens after we decolonize and get the land. Says Spice, “We’re in this highly destructive system, and it’s built on heteropatriarchy. It’s built on colonialism. And breaking out of that means having the imagination to think through other alternatives. For queer people and for Indigenous people alike, we’re already living those alternatives. And so the constructive project of building a different world is something that we’re already practicing. It’s not just saying ‘no’ to the pipelines. We’re engaged in that world-building project already. And I think that’s what draws us to land defence. We know we need to protect the territory, but we also need to build something else that’s going to continue to feed our relations into the future.”

simpson echoes Spice’s future-oriented vision and argues that queer and trans Indigenous youth are turning to digital media to widely disseminate knowledge production about their movements and land-defence strategies, thereby educating publics, finding space for their creative work that has been pushed out of institutions, and making updates about the rallies quickly available to Indigenous communities. Says simpson, “Memes are the way, really. Meme platforms were also conduits to the publicity that we had, [and] our jokes and our humour. And I think that’s something that is going to be explored further in the future. Memes were once discredited as a medium and an art platform. But I see that changing, because Indigenous meme-makers are open to revolution.”

I want to leave audiences with a directive from the Indigenous queer, Two-Spirit and trans youth leading actions for Wet’suwet’en. When I asked simpson what those youth organizing actions for Wet’suwet’en want, they urged others, “Listen! Listen to us. Listen to the youth. The kids are alright. I’ve never been more sure of the kids. These are some of the most radical people out there now.”

Christi Belcourt, WET’SUWET’EN / NO PIPELINES, 2019. Digital image.

Christi Belcourt, WET’SUWET’EN / NO PIPELINES, 2019. Digital image.