Issues of white supremacy as they pervade queer and trans communities were brought to national attention during the 2016 and 2017 Toronto Pride parades when Black Lives Matter – Toronto intervened to demand an end to the corporate integration of uniformed police officers into Pride festivities. In doing so, BLM – TO firmly reminded us that before Pride became a parade, it was a riot: Stonewall protestors were queer and trans Black, Indigenous and people of colour, and they were led by trans women of colour who armed themselves with bricks and rocks against an increasingly violent police force.

Issues of inclusivity within queer and trans communities aren’t limited to Pride festivities. Ultimately, they permeate the arts as well—such as through AIDS art. The necropolitics of AIDS art flared up in 2015 when the exhibition “Art AIDS America” opened at the Tacoma Art Museum with relatively few Black artists in the show, even though the Black community experiences some of the highest HIV rates in the US. Die-ins at TAM were organized in response.

Within the borders of Canada, Indigenous peoples are currently facing an AIDS crisis, and represent the highest statistics per capita of HIV-positive individuals and those experiencing low CD4 levels associated with AIDS. Yet Indigenous peoples remain ghettoized within, and largely absent from, what we consider to be AIDS art. The decimation of our communities experienced at the height of the AIDS crisis is a contributing factor to Indigenous erasure in AIDS art. Jolene Rickard once tearfully told me, “When you lived in New York [in the 1980s and 1990s], you just lost so many friends.” A participant in the online art project by Paul Lang, Archer Pechawis and Lorna Boschman, BigRedDice, corroborates, giving a greater sense of the devastating impact: “Not many people realize that we lost an entire generation.”

Queer Indigenous artists who have responded to love, sex, death and AIDS continue in the oral histories of contemporary Indigenous art communities. This sampling of Indigenous AIDS art cannot capture the enormity of its scope: all the AIDS quilts made in Indigenous communities across Turtle Island; the touring exhibition “Native Survival: Response to HIV/AIDS,” curated by Joanna Osbourne Bigfeather, which first appeared at Gallery of the American Indian Community House in New York and featured work from Ryan Rice, Skawennati and Nadema Agard—the documentation for which was destroyed in a fire; or the HIV-prevention basket Doris Peltier gifted me that was part of a series woven by relatives in what is now known as colonial New Zealand.

What I hope this selection of works can offer, at least, is a window into the beauty, grit and truth these Indigenous artists, and so many others, offer to AIDS art.

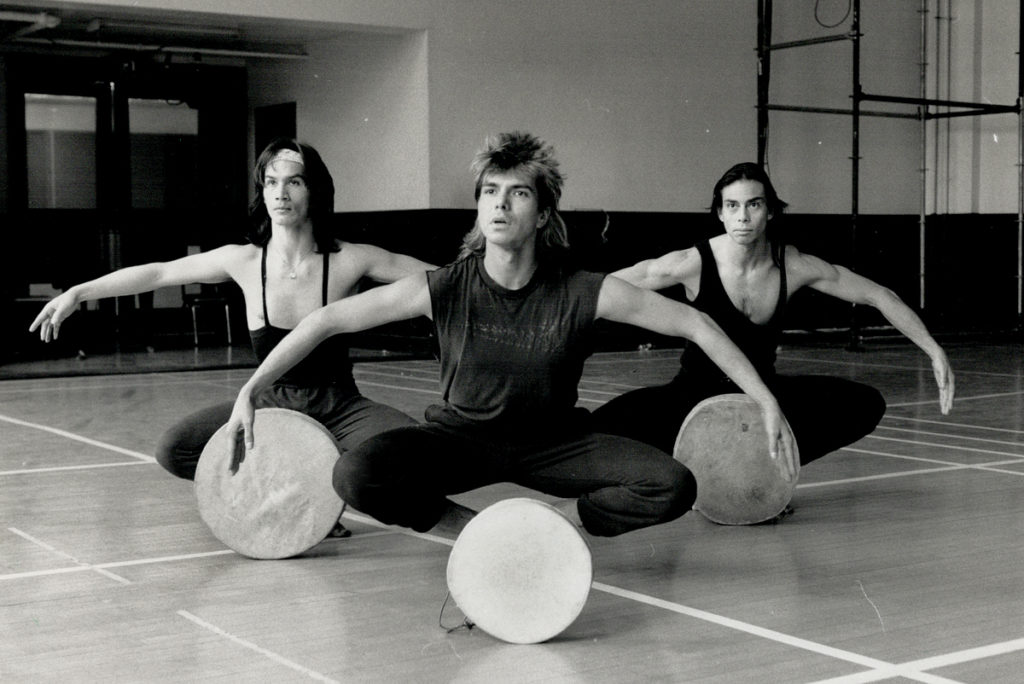

René Highway, New Song… New Dance, 1982/88

June Scudeler has done extensive work historicizing the work of Tomson Highway’s long overshadowed brother, René Highway. New Song… New Dance, choreographed by René Highway in 1982, was performed in 1988 with Alejandro Ronceria and Raoul Trujillo.

It was organized into three acts. In the first act, Andante, the dancers grow from being young boys in residential school experiencing unspeakable abuse—always intermingled with moments of boyish wonder and gay curiosity—to being men in the city, where they struggle to find a space for themselves and navigate the temptations of city life, like the exhilaration of anonymous sex in public washrooms.

René Highway’s curatorial notes for Andante contain words like, “hanging addiction/desire”; “shit/washroom sex”; “bondage”; “slapped down”; and “shaming.” Highway was conceptually making a connection between BDSM sex—the erotic fascination found in acts of bondage, shaming and anonymous sex—and complicated histories of sexual abuse associated with residential school. In doing so, he was creating a space to work through histories of trauma in a safe and consensual environment. In one scene, the choreographers visualize the tension of struggling to fit their Indigenous bodies into white customs by getting tied up and choked by their neckties—what Highway called “necktie abuse.” In another, the dancers repeat a squatting motion when the men engage in public sex, which relates back to the same squatting motion the dancers evoke when being rubbed in shit at residential school. New Song… New Dance was a defiant form of intergenerational trauma play and agential sexuality at a time when stigma and fear reigned.

Andante’s opening scene has naked dancers basked in white light, and this is described in Highway’s curatorial notes as, “the question of life and death and why…I reach up for the death figure…we mirror each other…I accept fate and continue.” As Scudeler thoughtfully notes, “It’s hard not to think of his HIV-positive/AIDS status as he symbolically goes into the light, since effective antiretroviral drugs were not available until 1996, six years after his death.”

Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew, archived works, late 1980s to early 1990s

Cree-French-Métis art theorist, curator, writer, new-media practitioner and performance artist Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew left this world in 2006. He was a seminal figure within contemporary Canadian Indigenous art’s shift toward digital and media art, and the Indigenous Net art and networked art movements of the 1990s. Though Maskegon-Iskwew is well known for his writing and Net art, there is a robust archive of his earlier installation and photography works completed from the late 1980s through the early 1990s, maintained by Vancouver’s Grunt Gallery.

In Body Wrap, for instance, Maskegon-Iskwew would wrap himself with white, cloth-like material, and photograph his body hanging in various positions in a warehouse in East Vancouver. In doing so, Maskegon-Iskwew compares his body to a corpse, at times even positioning his body on a wall as if it were art, with a somewhat humorous effect.

The humour is in the irony, of course. It’s a full-circle experience: Maskegon-Iskwew attempted to create work that reanimated the queer Indigenous body during his life, but what remains of him in this world are commodified representations of the dying Indian propped up on gallery walls.

In another series, Maskegon-Iskwew photographs himself naked in a bathtub that is only half-filled with water. He is wrapped in a plastic bag and gasps for air. Red twine binds him. Plastic wrap also appears in another photo series taken of various landmarks on Hastings Street in the Downtown Eastside—a ground zero for the AIDS crisis in Vancouver during the 1980s and 1990s. One particular photo was taken in front of the Roosevelt Hotel, and shows a figure whose head is wrapped in plastic walking down the sidewalk. Vancouver is the backdrop to an invisible but ominous cloud that suffocates and entangles Maskegon-Iskwew—he needs condom-like protection from it.

Paul Lang, Archer Pechawis and Lorna Boschman, BigRedDice, 2005

BigRedDice is an archive of the simultaneous shift in Indigenous art toward digital mediums and themes of love, sex, gender and intimacy. This shift became pronounced during the late 1990s, but was already underway in the early 1990s with work by artists such as Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew, Pechawis and Sheila Urbanoski’s Net art project isi-pikîskwewin ayapihkêsîsak.

BigRedDice is an interactive online art project developed from an earlier video installation by Lang and hosted on Pechawis’s website. It is an HIV/AIDS archive that transports the viewer through a collection of considerations, fears, desires and provocations about HIV/AIDS that are recorded in video responses. The visitor repeats the motion of “rolling the dice” by clicking on an image that plays a video loop of dice being rolled, and then navigates a collage of video clips that are populated depending on what number the visitor “rolled.”

BigRedDice uses the Internet as a space for connection and peer education around HIV/AIDS—a web of connection remarkably close to the concept of extended kinship. This web becomes a catalyst for intimacy, knowledge sharing and community response to HIV/AIDS. But this isn’t your mama’s HIV education video. It makes a point of collecting responses that are heady and complex, and grapple with provocative issues such as HIV culpability, pervasive stigmatization around sex resulting from the AIDS crisis and the public’s misperceptions about AIDS. One of the video participants even baits the judgmental viewer and plays on their biases, saying, “You know obviously I’m a ditch pig you can see semen oozing out of my ass. I’m getting loads after loads of cum. C’mon. Put two and two together figure it out. Where do you think I’m at?”

With BigRedDice, Lang, Pechawis and Boschman facilitate a dialogue between people of varied relatedness to HIV/AIDS, mirroring the online dialogue around HIV/AIDS that became accessible with newly available web technologies.

Terry Haines, The Aboriginal Video Quilt, 2005

Secwepemc-Welsh-Tsilhqot’n-French artist Terry Haines’s work is considered seminal in the realm of Indigenous AIDS art, and Haines’s partner, Aaron Rice, now holds the archive. Haines homed in on issues of HIV/AIDS throughout his multidisciplinary practice, and he had built a rich career that was poised to explode. Haines picked up the new-media practices of the generation of Indigenous artists before him who defiantly split from the Indigenous art community that preceded them, creating a stringent generational divide between those who moved into digital mediums and those who did not.

The Aboriginal Video Quilt is a mixed-media installation completed by Haines for an artist’s residency at VIVO Media Arts Centre (then Video In) in Vancouver. The concept for The Aboriginal Video Quilt derives from the AIDS Memorial Quilt project, intended to memorialize, square by square, the individuals lost during the height of the AIDS crisis, and those whose lives have been affected by their HIV-positive status.

Haines’s installation was meant to be a digital version of an AIDS quilt, and consisted of five monitors as well as mixed-media panels made of fabric, beads, Scrabble tiles, ribbons and fun fur, making for a humorous intermingling of ceremonial, trade and aesthetic materials—an urban Indigenous raver vibe, if you will.

Haines completed his last work, Coyote X, in 2013, weeks before his death. Coyote X finds Haines on a Vancouver beach spray-painting rocks collected from the shore with red positive signs: a homage to the city that defined his experience of contracting and living with HIV, nearly 30 years after Maskegon-Iskwew similarly marked East Hastings.

In making The Aboriginal Video Quilt and Coyote X, Haines created his own digital squares for the AIDS quilt, which is now pieced together by his lover Aaron Rice, just as the squares of textile-based AIDS quilts were sewn into place by the kin who mourn those we have lost.

Correction Notice: This post is adapted from the article “We Lost an Entire Generation” in the Fall 2017 print issue of our magazine. The subtitle for this article on page 138 in the Fall 2017 print issue of Canadian Art erroneously suggested that the artist Archer Pechawis is deceased, an inaccuracy that was repeated in the “This Issue” text on page 18. The original article text also misattributed the interactive website, BigRedDice, as the work of Archer Pechawis. In fact, this work is an online collaboration between Paul Lang, Archer Pechawis and Lorna Boschman, based on an earlier video installation created by Paul Lang.

Canadian Art deeply regrets the errors and sincerely apologizes for any grief or harm that this has caused Mr. Pechawis and his family. The publication also apologizes to Paul Lang and Lorna Boschman for the misattribution of their work, as well as to Lindsay Nixon, the author of “We Lost An Entire Generation” and our Indigenous editor-at-large, for mistakes introduced after the fact-checking process.

René Highway, New Song... New Dance, 1982/88. Archival photograph, 15.7 x 23.4 cm. Courtesy Frank Lennon/Toronto Star/Getty Images.

René Highway, New Song... New Dance, 1982/88. Archival photograph, 15.7 x 23.4 cm. Courtesy Frank Lennon/Toronto Star/Getty Images.