“The last keynote speech I give—the reason I want this to be the last, and I say that respectfully—is because I grew up in Métis and non-status Indian politics. I have been in conferences such as this since I’ve been a small girl, perhaps even while I was still in my mother’s belly.

I have heard talks, I have heard the hope, I have heard promises for change. I myself have been inspired at conferences, and perhaps those were in my naïve days when I didn’t know then what I know now—and that is what is happening to the earth.”

So began Christi Belcourt’s address, “The Revolution Has Begun,” at Maamwizing: Indigeneity in the Academy, a conference held at Laurentian University in November 2016.

As she made clear from the outset, Belcourt wanted this to be the last keynote for her, ever, having witnessed the vast amount of resources poured into academic and political gatherings—events where children, families and Elders, to a large extent, are not present, and where powerful expressions of hope and change too often do not result in actual change outside of the conference venue.

Kahnawake Mohawk scholar Audra Simpson, author of Mohawk Interruptus, has critiqued the framework of reconciliation for attempting to “harmonize and balance a fundamental disjuncture: a sovereign state that was and is unwilling to rescind its false claims to Indigenous land and life, and Indigenous struggles for that land and life as sovereignty.”

Simpson’s quote drives to the heart of Belcourt’s own critique of systems of power, and her assertion of the need for Indigenous communities to build and rebuild from within.

“Reconciliation is neither comfortable nor convenient, and it shouldn’t be,” Belcourt herself noted in that hoped-to-be-final keynote speech. “Reconciliation without land returned and a correction of all that has resulted from our dispossession is not even possible.”

She added: “Politically…I see the word reconciliation being used to rebrand the existing insidious assimilationist policies of the government.”

Belcourt’s practice overall bridges the immense efforts of self-organizing, resisting and sharing knowledge on the land with the space of the gallery, yet works to decentre the colonial gaze inherent in these institutions.

Further, Belcourt’s work could be described as both resurgent and conciliatory, of nurturing relations through kinship networks that are place-based, inter-species and otherworldly, and in turn demonstrates, through beauty, strength and wonder, that other (to colonial capitalist) ways of being in relation to one another and to the earth are both possible and desperately urgent.

Perhaps this is a lot to ask of the artist, or of art more broadly, but Belcourt challenges us to think of the artist away from the individual and to think of art as interwoven with the variegated fabric of life. And she challenges us to walk softly in careful consideration of where and how we step.

In my recent phone conversation with this Michif (Métis) artist—whose ancestry originates from the historic Métis community of Manitou Sakhigan (Lac Ste. Anne) in Alberta and who was raised in Ontario, where she is currently based in Anishinaabe territory on the North Shore of Lake Huron—we spoke about her recent work, much of which is geared towards revitalizing Indigenous culture, language and land-based knowledges as well as drawing attention to the urgent situation facing the planet as a result of resource extraction and climate change.

Indeed, Belcourt’s position of less-talk-more-action is reflected in her wide-ranging practice as a visual artist and community organizer; this positions her artistic practice within a continuum that, for Belcourt, is related to offerings, ceremony, resistance, resurgence and everyday life as a Michif woman while simultaneously calling to our shared responsibility as human beings as one species among many.

“I do not feel my work is separate from the work of the hundreds and thousands of Indigenous Peoples and Nations who are doing work that brings health, healing or light to their communities and yet go unheralded,” Belcourt said upon receiving the Governor General’s Innovation Award in 2016. “These awards are coming at a time when Canada is gearing up to celebrate its 150-year anniversary. Unfortunately, it is an anniversary that will not hold the same celebratory feeling for many Indigenous Peoples as it does for Canadians.”

Belcourt centres her practice in the relationality of all beings and the responsibility arising from this.

“In Indigenous ways of thinking and knowing and being, the concept of walking softly on the earth is not a quaint thought,” she tells me over the phone. “It’s a practical thought about preserving life on the earth.”

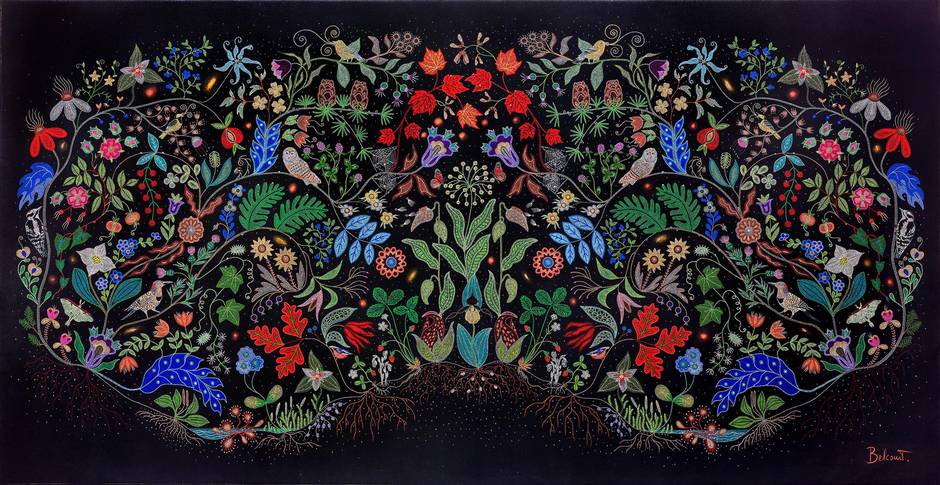

Christi Belcourt, Water Song, (2010–11).

Christi Belcourt, Water Song, (2010–11).

Belcourt’s well known paintings of floral motifs—one of which is going on view starting June 22 as part of “Wapikwanew: Blossom” at Karsh-Masson Gallery in Ottawa—evoke customary Métis beadwork designs. Water Song (2010-11)—which is in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada and served as the basis for Belcourt’s collaboration with the Italian fashion house of Valentino—are profoundly sumptuous. Their rich colours are dotted upon a black velvet-like background, and they draw upon a deep understanding of the medicinal uses of plants and the need for clean water to sustain healthy ecosystems.

A recent painting directly addresses the artist’s concern for water systems. The Great Mystery of Water (2016) depicts a school of fish in Belcourt’s beadwork style combined with a more fluid brushstroke. The fish, which look to be walleye that are found in the Great Lakes and Northern Ontario waters, swim in a diamond formation and are surrounded by water adorned with jewel tones. Trails of gold stream from the fishes’ fins as they cut through the water.

This painting is flat and decorative yet full of movement and vitality, a testament to the artist’s developed sense of composition and rhythm. Belcourt’s creative collaborator Isaac Murdoch is featured in a video promoting a petition to recognize the Great Lakes as a living being, and Belcourt’s painting expresses this message through aesthetic means.

Christi Belcourt, The Great Mystery of Water, 2016.

Christi Belcourt, The Great Mystery of Water, 2016.

The aesthetic pleasure derived from these works is not meant to elevate the natural world to the status of art, but rather to signal the connection to the natural world as itself transformative.

“Images are sources of power and have the ability to confront history,” writes curator Candice Hopkins, drawing from the writings of philosopher Vilém Flusser, in her essay “Why Can’t Beauty Be a Call to Action?” This power derives from what Flusser terms “the world of magic, a world in which everything is repeated and in which everything participates in a significant context,” as opposed to the world of history, which is a world of causes and consequences.

Such images, include, I would argue, Belcourt’s paintings, which dazzle with visual delight and abundance while also confronting the crisis of history—including our colonial past and present—by making visible the “magic” or mystery contained in the world around us.

The images Belcourt creates also circulate in significant contexts beyond the art world.

One of her images, Water is Life (2016), has been silkscreened on banners in what that artist calls “community-art builds,” screen-printing sessions organized by members of the Onaman Collective, which is comprised of Belcourt, Erin Konsmo and Isaac Murdoch.

Both Belcourt and Murdoch have made several such images available for free on the collective’s website to be used in actions and marches. The banners made during the community-art builds are mailed to water protectors and water actions across North America with the request that they be forwarded on to another protector, another action as they continue to be needed.

Christi Belcourt, Water is Life, 2016.

Christi Belcourt, Water is Life, 2016.

The phrase Water is Life speaks to “the popular Lakotayapi assertion ‘Mni Wiconi’—water is life or, more accurately, water is alive,” as Jaskiran Dhillon and Nick Estes explain in “Introduction: Standing Rock, #NoDAPL, and Mni Wiconi” on the Cultural Anthropology website.

Belcourt’s imagery for this phrase, in painted form, depicts a woman with ceremonial markings—tattoos on her face and a skirt wrapped with blue and green ribbons—pregnant with child (described by Belcourt as a “Thunderbird baby”), raising her fist in the air. Water courses through her womb and gives her something to hold onto before returning to the clouds/Thunderbird beings that send rain to replenish her container.

Belcourt’s work here and the message it represents begins to unravel—at least in aesthetic terms—the intersectional violence of colonialism and capitalism that are propagated through gender, race, class and sexuality. Indigenous women are differently impacted by the gendered effects of resource extraction industries, which is incommensurable with the belief held by many Indigenous cultures that women hold knowledge of the water and are its protectors.

Belcourt’s practice also moves beyond representational strategies, beyond the symbolic. She is particularly interested in actively revitalizing Indigenous knowledges and ways of being in relation to the land.

Working with the Onaman Collective, whose name references traditional materials used in red ochre paint and in treating wounds, Belcourt has been raising funds for Culture Camp Forever, which has recently been named Nimkii Aazhibikong. (An online auction supporting the camp started earlier this month, and continues to June 29.)

Youth-led with Elder guidance, the year-round camp will be a place where land-based activities like trapping and gardening, self-governance and ceremony can take place daily, becoming normalized as these practices once were. Already, some of these activities have taken place in shorter-term bursts.

Christi Belcourt and Isaac Murdoch, Reconciliation with the Land and Waters, 2016. Acrylic on buffalo robe. Buffalo robe gifted to Onaman Collective by Grand Chief Derek Nepinak. Exhibited at #callresponse at grunt gallery in Vancouver.

Christi Belcourt and Isaac Murdoch, Reconciliation with the Land and Waters, 2016. Acrylic on buffalo robe. Buffalo robe gifted to Onaman Collective by Grand Chief Derek Nepinak. Exhibited at #callresponse at grunt gallery in Vancouver.

Recently, I worked with Belcourt and Murdoch on #callresponse, co-organized with Maria Hupfield and Tania Willard in partnership with grunt gallery in Vancouver.

Belcourt and Murdoch’s collaborative work for #callresponse, titled Reconciliation With the Land and Waters (2016), begins with ceremony on the land—a move to restore the practice of offerings that was at one time commonplace.

A record of these activities was then painted on a buffalo robe and placed in the gallery space at grunt, signalling a relationship with land and the other-than-human beings that comprise it as exceeding the colonial concept of land as property—as well as current appeals for a reconcilable future, at least where the nation-state is concerned.

As the #callresponse project tours—currently, it is on view at SAW Gallery in Ottawa until July 30—the robe will eventually be returned to the artists to be used in teaching and storytelling, perhaps at the Culture Camp Forever.

“We are in sacred times,” Belcourt said near the end of her lecture in Sudbury last November. “We are in a spiritual battle for this earth. We need a revolution of people who are willing to follow the pipe, not have one. The earth needs us and the future generations have us and we are out of time for the waters.”

She continues: “So I apologize if this was not the keynote you thought you would get. And like I said, I hope that this will be the last keynote speech ever. Because I want to spend all of my time, from here on in, on the land, building the Culture Camp Forever.”

The final thought she left her audience with?

“All good stories end in a revolution.”

Tarah Hogue is a curator and writer based in the unceded Coast Salish territories of Vancouver. In September, Hogue will join the Vancouver Art Gallery as its first senior curatorial fellow in Indigenous art.