Video (Intermedia)

Video is the predominant medium of the 21st century. Video’s power and relevance stem from its unparalleled capacity for mixing and dissolving into other media. Video embodies film, television, performance and surveillance, and has become the ultimate living and breathing, matter-of-fact medium of all forms of advancing digital telecommunications. High-resolution, real-time video streaming, with synchronic, spatially rich digital audio, is the immediate destiny of wireless digital telephony. Text messaging and still-picture phones are paving the way for full-motion, video-based personal telecom.

Video is a liquid, shimmering, ubiquitous medium that absorbs everything it touches. This liquidity makes video synonymous with intermedia, the art of filling the gaps between media. Today’s media culture and media art are composed of complex, hybrid forms of multi-sensory information. Nothing is very pure and one-dimensional these days. Print media, from on-line newspapers to blogs, feature video feeds. Books talk. Music and advertising are synonymous. Digital cable television functions like a DVD player. Audiences are active, scanning multiple sources of information, usually simultaneously. Artists choose to work in media that overlap and offer multiple paths to and from audiences. Video flows through and around all other media. Video saturates—it really connects.

Contemporary artists infuse their images, sounds and ideas into the world through video. Dick Higgins, the Fluxus artist and philosopher, wrote in 1966 that “Much of the best work being produced today seems to fall between media.” The compartmental approach to art and culture, where painting was separate from sculpture, music was devoid of moving images and cinema differed substantially from television, had come to an end. The phenomenon of intermedia, in which new hybrid relationships are forged between media and genres, has been the result of artists of all disciplines breaking free of the constraints of their individual practices. The desire to redefine the boundaries of artistic expression has involved collaboration, interaction and the redefinition of strategies, aesthetics and audience.

It is no accident that video emerged from television in the mid-1960s, which saw the heyday of Pop art and the birth of Happenings and conceptual art. Video was (and still is!) the ultimate tool for documenting and amplifying these comprehensive, inclusive strategies through instant replay and systematic feedback.

Today’s art, more than ever, progresses toward total integration. Video-based collectives are springing up everywhere. Such groups are experimenting with the interaction between visual media, music, movement, theatre, poetry, design, propaganda, the sciences, et cetera. These experiments are most often authored and disseminated in video, that ubiquitous, unparalleled medium for defining psychological, social and political attitudes. Identities are being modified, social gaps are being bridged and political actions are being initialized as we speak.

In fact, making video is like talking. In its essence it occurs in real time, permitting our minds to run ahead of the moment. Video is intimate and immediate (quick as light), and it is positively inclusive. Video will be at the heart of all forms of digital telecom in the near future. Video (intermedia) fills all the spaces between the arts today.

Video (intermedia) features tomorrow today.

Video Just Under Forty

Video is just under forty years old. As a technology goes, that is fairly old. Video was spawned by television. Video was first understood to be the visual component of television. Television’s picture was video. This initial manifestation of video goes way back to the early days of the 20th century, when there were experiments in transmitting images from place to place using radio waves. Images of earthly reality were translated into signals and thrown onto little screens that emitted, rather than reflected, light.

The magic of cinema was already old hat. It was great sitting around in the dark with hundreds of other people watching stories unfold in the flicker of the big screen, but some people wanted cinema beamed into their homes in the worst way. Cinema was taken out of the movie theatre and into the home by television, that motion-picture appliance. The first televisions were like floor radios. They had big speakers and tiny round screens. The first TV screens were like oscilloscopes. Besides the fact that television was radio with pictures, there was one very important difference between television and cinema. The television screen was also a porthole onto the world. Television delivered cinema into the home, and it also delivered live events in real time, as they were happening.

From its beginning, television delivered cinema into the home and it extended time and space by connecting its audience to live broadcasts from remote locations. Television was a delivery system for cinema and video. It delivered two very different media into the home, and it delivered the attention of its audience to advertisers and governments.

Television was the ultimate delivery system for audiovisual content in the 20th century. It was not much of a medium in its own right. It was a network. Television was characterized by a synthesis of cinema and live drama intercut with stretches of video (live and taped); this rich, high-contrast collage was glued together with magazine graphics and lots of text. The beauty of television was its transparency. It was a delivery mechanism for everything that came before it, and it introduced video, which was synonymous with television until the mid-1960s, when video was extracted from television and became a medium in its own right.

The first portable video recorders (Portapaks) were introduced in the mid-1960s. Television had introduced the idea of video instant replay, where a live event was enhanced by instant reviews of recorded action. The Portapak took this power to the street. Portable video is a powerful cybernetic technology. It generates a duplicate, parallel world in real time, and it provides instant feedback through playback. The impact of an event or gesture is amplified through instant replay, and behaviour is modified by the introduction of video feedback. Television used the power of video to transcend cinema. The video dimension of television multiplied time and space at the speed of light and permitted everyone on the network to travel to remote places through the television’s window. Events and places and people were fixed in memory through replay. Repetition was used to give weight to highlighted appearances and events.

Over the last couple of decades of the 20th century, television was fully decentralized. It was spread as video. The VCR was developed to continue television’s mission to distribute cinema into the home. Video became synonymous with home movie consumption. Portapaks evolved into camcorders, personal video instruments for recording everyday life and shaping behaviour through feedback. Appearance could be studied through replay. Personal histories were recorded. Identity was defined. Self-consciousness was overcome. Parties were energized. In the first decade of the new millennium, picture phones finally arrived in the form of webcams. The computer has become the next major network, and, like television, the computer is not much of a medium in itself. The computer is a typewriter, photo lab, movie theatre, video studio, game parlour, et cetera, et cetera. The so-called digital revolution is a cleaner, crisper way of doing many familiar things.

Television is still an important network for promoting and distributing cinema, and for linking audiences to spectacle via video. It also promotes the medium of video through the phenomenon of “reality television.” Reality TV is television under the extreme influence of video. Video, as a medium, has a fundamentally real, literal quality. Video, the technology, is an instrument for cutting through fiction and fantasy. Raw video is at the very foundation of the news. The smouldering wreckage of a car bomb, accompanied by the screams of its living victims, cannot be more authentic in any other medium. Video can also be dressed up to look like cinema. In fact, reality television is a cinematic, theatrical distortion of video. In reality television, porn actors and models pose as ordinary people. These “real” people are humiliated for our vicarious pleasure. They are overexposed for what they really are: imposters to be consumed and discarded. Script, for the most part, has been eliminated. Improvisation is recorded and examined during replay. Performance and replay have been adopted as the formal structure of television influenced by video.

Video now straddles the two major networks—television and computer-based telecommunications. The television broadcast/cablecast now shares an audience with the digital video stream. Video, the electronic, digital medium for the conveyance and storage of image and sound in real time, has become the primary medium of both television and the computer. Video, although inherently non-cinematic, has also become the technical base of cinema. This has caused some confusion, for cinema’s time and look have never been literal or real. Video is the antithesis of fantasy and fiction. Cinema, in video, is now forced back to its roots, to the live stage and to animation (both character animation and special effects).

Acting is more difficult under the scrutiny of video’s unforgiving critique of reality. Unfortunately, the use of video to make cinema will result in more products resembling reality television. Animation, on the other hand, will flourish in and across the triumvirate (cinema/television/video). Animation’s concrete, explicit articulation of imagination will fit nicely in any context provided by cinema, television or video.

From now on, all serious attempts to critique cinema, television and video will be conducted in digital video, video that circumvents the gap between television and computer networks. Experimental cinema, the self-conscious, critical attempt to broaden and reform the use of film, has been completely eclipsed by video. Besides the issues of accessibility and cost, working in film to critique television, video and computer culture, or even today’s digital cinema, makes very little sense. The medium of film is too limited. Film connects us to the past, to a time when cinema was an experience that was clearly separate from and unattached to the world in which we live and breathe.

While television, video and computers are hardly flesh and blood, these media are integrated into our world in far more pervasive ways than cinema. The electronic, digital media form a parallel, simultaneous reality to our concrete, physical world of bodies, architecture, landscape and atmosphere. Networked video, video streams that will flow in real time and in high resolution, offer a material manifestation of reality, a substantial descriptive analogy of life at the moment it appears before us.

Artists are drawn to media that connect them to the world, to life itself. Right now, and in the foreseeable future, digital video is the most direct, literal, explicit medium we have for exploring and manipulating reality. The arguments against video, that it is inferior to film in terms of resolution, or that, as a push-button technology, it’s too easy, are lame. Digital video resolution, while still currently lower than photochemical media, is far more than adequate when combined with its rich, integrated audio and its speed-of-light transmission rate. Unlike film, digital video is technically unlimited in terms of future resolution. The arguments that video is not a medium worthy of artistic use because it isn’t prohibitive financially and technically (like film), or isn’t nearly impossible to work in because of unions or gender discrimination (like film), are hard to fathom.

Getting back to reality, video offers incredible resolution as a philosophical instrument. Video permits the absolute transfer of reality into a malleable material, the simultaneous, digital architecture of optical/acoustic perception. Video is a hyperextension and reinvention of optical/acoustic reception. It extends the eye and ear, and, in its electronic, digital quickness, it replicates and supplements the nervous system, enhancing focus and memory. Let’s face it, non-mediated reality has its limitations in terms of space and time, in terms of the kick we get out of it. Video offers more than an escape from non-mediated reality; with its moving image and dynamic sound, and its subtle displacement, it provides us with a means for measuring the truth of the moment in real time. It allows us to connect with the world absolutely. Through acts of observing, affecting, recording and retransmitting reality, we are empowered to critique reality itself. Self-awareness and criticality are at the heart of the art-making process.

Art is a perceptual and intellectual activity conducted by people who question and often despise the status quo. In the 21st century reality is defined by layer upon layer of media, often by media stacked high upon one another, unattached to any absolute truth (no matter how momentary and fleeting any sense of truth may be). Video is not only the best medium for critiquing television and cinema, its media next of kin, it is also a perceptual, philosophical instrument for questioning reality in broader terms, for finding problems with the way we connect with the world, and doing something about it.

Video Not Film

It’s video, not film.

It pisses me off the way video is being called film, so carelessly. In a review of the recent premiere of a feature-length work of video art, a newspaper columnist repeatedly stated that the artist’s “film” was blah, blah, blah. The artist herself had used the f-word to launch her video feature into the entertainment section of the newspaper, and thus into the public’s eye. The columnist wasn’t sensitive enough to make the distinction between media. Why should we expect him to make the distinction? The artist herself had decided to promote her video as a film.

Film is the term for all moving pictures in the world of entertainment. The general public has been conditioned to want to see film. When the medium of video is used to “film” a movie, the director is not likely to admit he or she is working in video. Film has been the modus operandi for more than a hundred years. Film’s roots are so deep that any kid with a video camcorder will say she is “filming” when shooting video. Since the commercial success of The Blair Witch Project (1999), “film” collectives working exclusively in video literally outnumber garage bands.

Film’s main values are storyline and the illusions necessary to make cinematic narratives believable. I’m lumping all film together with commercial cinema, because independent film today does little except try to emulate the mainstream, and experimental film has been completely eclipsed by video art. Working in 16mm or 35mm film is prohibitive financially, and, let’s face it, the medium of film looks tired and has major distribution and exhibition problems compared to video. The medium of video is the technical foundation of filmmaking today, but you’d never know it. Film advocates are shrouding video in a nostalgic cinematic cover-up of immense proportions. It’s hard to make video look like film, but a lot of people are trying very hard. When they succeed, the medium of video is diminished, forced to do things it isn’t well suited for, like encouraging audiences to suspend disbelief.

Video is a direct electronic analogy to the world in front of the camcorder. It lets us see exactly what we’re looking at, explicitly. Video’s fundamental strength is its ability to transmit information directly through its cool, elegant, instrumental conveyance of image and sound.

Let me tell you a story about the difference between film and video. Martin Heath, a long-time film purist and expert film and video projectionist, who runs the experimental-film venue Cinecycle in Toronto, asked me if I had seen video projected using one of the new Texas Instruments chips. The Texas Instruments system is called DLP, Digital Light Processing. Martin told me it looks just like 16mm film, only better.

Heath advised Reg Hartt, the renowned film historian and archivist, to buy a DLP projector for his home theatre. Hartt was encouraged to keep his projection-screen size relatively small to maximize the intensity of the DLP video projection. Heath was there the first night Hartt fired up his new home theatre. Hartt had an archival DVD of The Iron Mask (1929), directed by Allan Dwan, starring Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. This DVD release is state-of-the-art film on video (the disc was made in part from a pristine 35mm print of the film held by the Museum of Modern Art). Heath and Hartt sat down to evaluate the performance of the DLP projector. In the first scene of The Iron Mask, Fairbanks emerges from a castle door, sword in hand. To the horror of Heath he could see the castle was made of papier mâché plastered over chicken wire. The video projection was too good. The splendid digital video image had shattered the illusion of the film. The castle looked totally fake.

This is a good example of the difference between video and film. The explicit, bare-bones, no-nonsense video image had cut through the illusion of film. The image was too clean. The whole frame was too matter of fact. I’ve heard of tricks used by contemporary filmmakers to make video look like film. They actually use vaporizers to thicken the air with steam to soften the way a room looks on video. Or they use video camcorders with reduced frame-rates (reducing the fidelity and detail of the video frame) to make video look like film. Basically filmmakers miss the “hop” of the film image, the black between film frames. These cosmetic, retro treatments of the video image are undertaken at the expense of the vitality of the medium of video. I, for one, am sick of seeing the retrograde sensibilities of film painted over video for commercial or, worse, purely nostalgic, anachronistic purposes.

Fuck film. The dead ideas of film are being heaped onto video. Cinematic history is like a ball and chain. Video, as an inclusive, soluble medium, is having difficulty defending itself from the weight of this affliction. It has become fashionable to declare, “I ‘filmed’ this or that with my digital camcorder.” In this ahistorical time, it has become common to use the nomenclature of film, the predominant medium of the 20th century, to declare one’s existence in the 21st. Everyone is going retro.

Most of the curators of film and video at major museums are the strange bedfellows of film chauvinists. They love to decorate the galleries with projections of fragments of film and video formatted in loops. Sometimes museums actually project film itself, providing the public with the luxury of experiencing a nearly obsolete technology. It seems particularly fashionable to shoot in film and then project in video (to get very close to the film look). Although this kind of thing goes against the strengths of the video medium, cinema in the museum is generally called “video” installation.

Interviews with the artists who make video installations often reveal their ultimate goal is to make a feature film someday. They start their film careers in museums because film that doesn’t move (in time) and doesn’t tell a story can still manage to hold a wall nicely in competition with paintings, an even more arcane medium than film. A lot of video-installation artists are making video paintings these days. They shoot moving images that move very little, sometimes simply re-enacting the content of historic paintings, and project them at cinematic scale on gallery walls, or on hotter, high-resolution plasma screens. Slow motion is the main device of video painting. For the most part this perversion of video is driven by attempts to commodify moving image as object.

Video, when served straight up (neat), is so direct and raw and explicit, it’s almost embarrassing. The camcorder reveals the world with X-ray levels of clarity. There are no illusions. Look at what video has done to television! Reality television is in fact the aftermath of video’s impact on television. Beginning with America’s Funniest Home Videos (which first aired in 1990), we are now subjected to a plethora of extreme, inane behaviour (scantily clad fashion models eating worms, for instance) in the name of reality. Video’s direct, explicit clarity drives people crazy. Video has affected all sectors of society (sports, surveillance and security, dating, shopping, cooking, sexuality), and yes, it has affected film.

Unfortunately, video, that ubiquitous, liquid medium of the 21st century, has absorbed film and, in its saturation of all things cinematic, it appears to be something it isn’t. Video is not film. In this digital era, when computers are everywhere and everything is converging with digital telecommunications, video, too, has become digital. Universities are now offering courses in “digital cinema” (which are of course taught using video camcorders).

Video technology is still in its early days (portable video is less than forty years old). Video will continue to proliferate and gain power well into the 21st century. It will supersede film and television, becoming a leading, discrete medium and part of a major triumvirate of media (cinema/television/video).

Video will be the central channel for advancing digital telecommunications technologies of all forms, riding and boosting the energy of the personal-media explosion. In the meantime, film enthusiasts can attach as much cinematic history as they want to video. They can call video anything they like. I’m going to call it video.

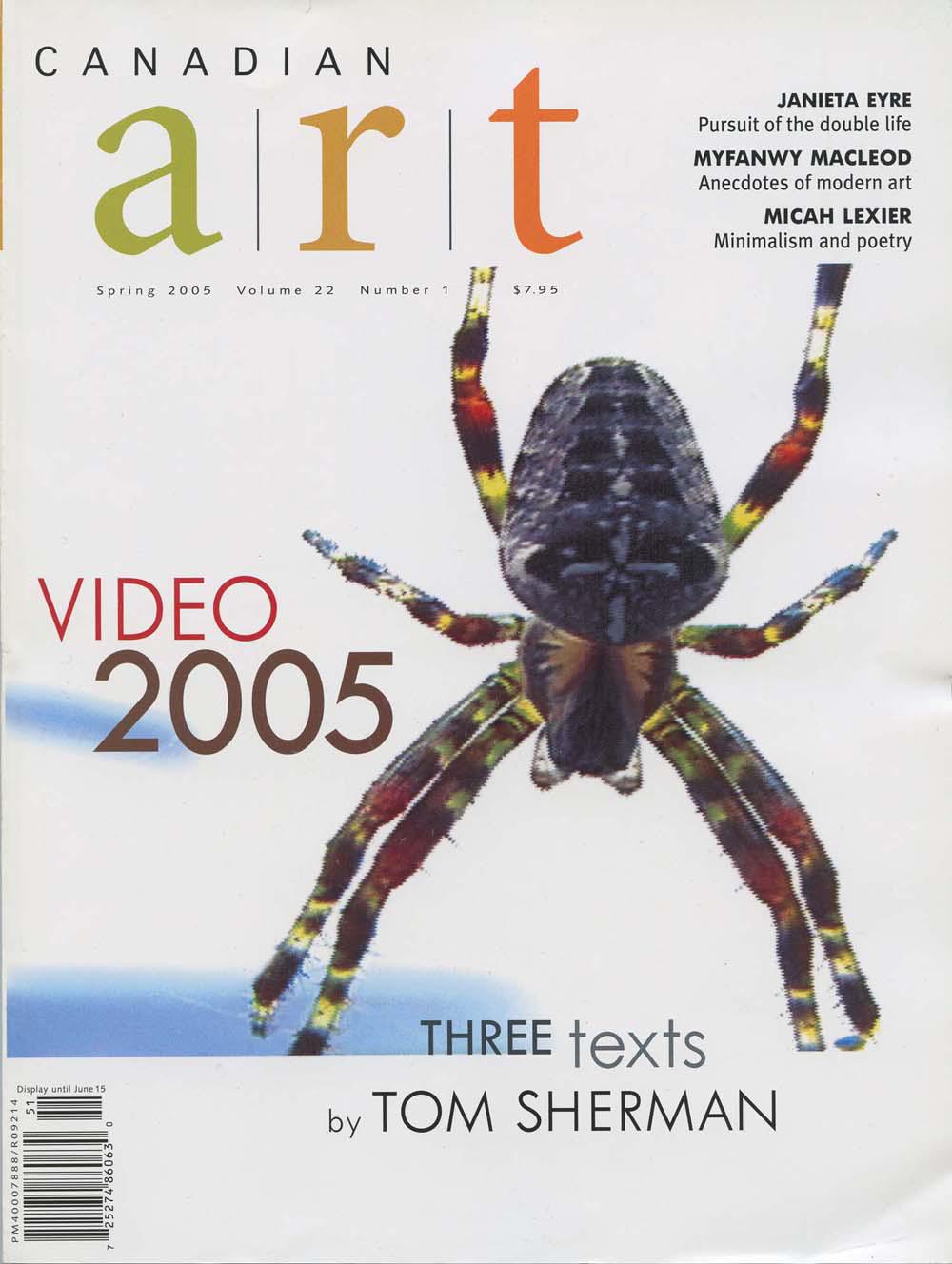

This is the cover story from the Spring 2005 issue of Canadian Art.