Artists’ studios rarely have a transporting effect. Paintings are in so-so half-finished states; installations are lying around in their constituent parts. This doesn’t mean that studio visits aren’t interesting—they’re fascinating, but they offer an analytic satisfaction rather than an aesthetic one. I enjoy them in the way that a fashionable person might like seeing a seamstress hand-pick a zipper, or a gourmand might appreciate watching Great British Bake Off—a revealing and useful exercise that’s nevertheless at a remove from the true joy of the thing.

But Montreal-based Vicky Sabourin offers a noticeable exception to this rule. When I stepped into her studio at the Banff Centre this summer, I stepped into another world. A felted bobcat, which had an uncanny realism despite being obviously handmade, was draped over a moss-covered mound in the middle of the room and surrounded by twigs, sculpted animal paws, signs scrawled with “PRIVÉ” and ceramic replicas of steel jaw-traps and bullet casings.

The studio shouldn’t have surprised me. Sabourin can turn even the most unlikely of spaces into venues for her form of strange, otherworldly storytelling.

Vicky Sabourin performing Iridescents at Hamilton Artists Inc. during the 2016 Hamilton Supercrawl. Photo: Vicky Sabourin.

Vicky Sabourin performing Iridescents at Hamilton Artists Inc. during the 2016 Hamilton Supercrawl. Photo: Vicky Sabourin.

The second time I saw Sabourin, she was on the ground, sweeping up golden birdseed while cradling a basket of felted pigeons in the middle of the Hamilton Supercrawl in September. Though Sabourin began her performance inside Hamilton Artists Inc., she eventually moved outdoors, where crowds of people were ambling past with churros and sunburns.

“When I was inside the gallery and throwing the little gold pebbles and picking them up one by one, I was expecting that maybe someone would come and decide to help me. But I know that people are used to keeping their distance because they are so afraid of messing up the performance,” Sabourin told me later over the phone.

“As soon as I stepped outside, that layer is completely gone. People thought it was quite strange, when I was throwing the gold pebbles for the pigeons. But as soon as I was on my knees and trying to pick up all of the pebbles or seeds, suddenly for them it was not a performance piece—they thought I had dropped my jar and I was someone in need of help.”

Vicky Sabourin performing Iridescents at Hamilton Artists Inc. during the 2016 Hamilton Supercrawl. Photo: Vicky Sabourin.

Vicky Sabourin performing Iridescents at Hamilton Artists Inc. during the 2016 Hamilton Supercrawl. Photo: Vicky Sabourin.

Sabourin likes to keep her audience guessing, and “Danse Macabre,” her show on view at Quebec City’s L’Œil de Poisson until November 20, which includes the work she produced in Banff, is no exception.

The show has many reference points—from the Medieval allegories of death coming to fetch its victims in an unavoidable, equalizing dance, to Marcel Duchamp’s harrowing Étant donnés—but perhaps the strangest source is a YouTube hunting video Sabourin stumbled across. Posted by Richard Hiltz, the five-minute video begins like any other machismo-tinged documentation of a kill, with Hiltz removing a limp, dead bobcat from a trap. And then, two minutes into the video, the cat’s limbs begin convulsing, as if animated by some invisible puppeteer.

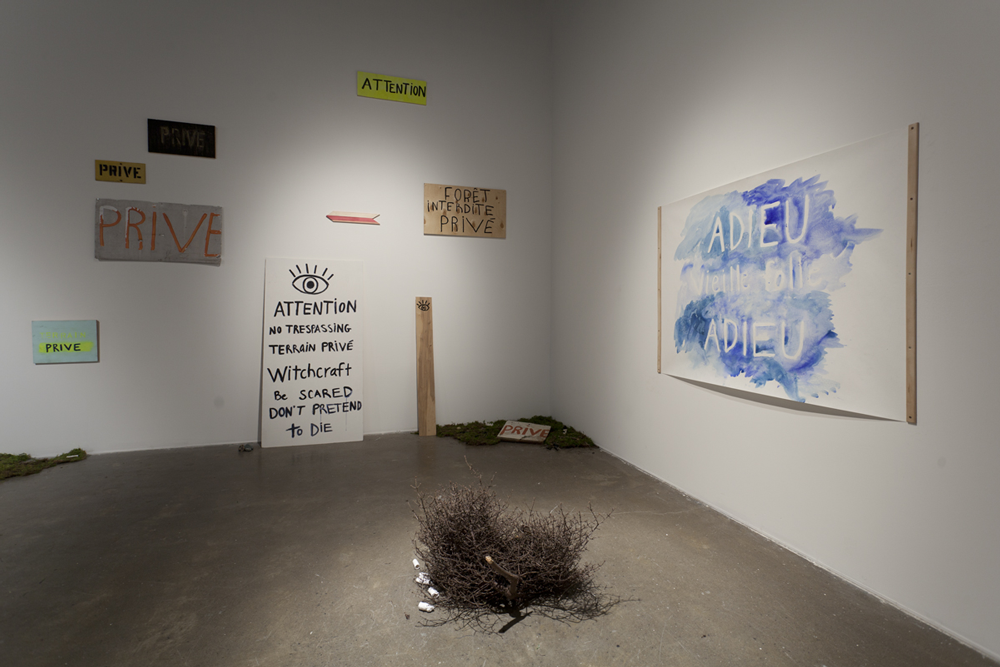

Vicky Sabourin, “Danse Macabre” (installation view), 2016. Image courtesy L’Œil de Poisson. Photo: Charles-Frédérick Ouellet.

Vicky Sabourin, “Danse Macabre” (installation view), 2016. Image courtesy L’Œil de Poisson. Photo: Charles-Frédérick Ouellet.

Sabourin’s fascination with this video spurred the creation of her felted bobcat, which recreates the dancing movements of its counterpart in a stop-motion video (created in collaboration with Elisabeth Belliveau) that can be glimpsed through the peephole of small wooden shed built out of old barn wood.

Vicky Sabourin, “Danse Macabre” (installation view), 2016. Image courtesy L’Œil de Poisson. Photo: Charles-Frédérick Ouellet.

Vicky Sabourin, “Danse Macabre” (installation view), 2016. Image courtesy L’Œil de Poisson. Photo: Charles-Frédérick Ouellet.

Yet, while the promise of this video beckons, audiences will need to engage in some trespassing to take it in: Sabourin has filled the gallery with signs bearing variants of the warning, “Private.”

“When I go to my family cottage, there are “Privé” signs everywhere. This place has been a very strong inspiration for my work and is the foundation of my real and fantasized connection with nature,” she explains.

“The idea that wilderness is a private space, or privately owned is very strange…. Many of these ‘Privé’ signs are misspelled, made with a very strange aesthetic and plastered on the trees all around. You can see different generations in these signs. They are often handmade. Even if they are utilitarian, they look almost like folk art. Some are old and rotting, others are newer, manufactured and more generic.”

Vicky Sabourin, “Danse Macabre” (installation view), 2016. Image courtesy L’Œil de Poisson. Photo: Charles-Frédérick Ouellet.

Vicky Sabourin, “Danse Macabre” (installation view), 2016. Image courtesy L’Œil de Poisson. Photo: Charles-Frédérick Ouellet.

Like her ambiguous Supercrawl performance, the signs mount a kind of challenge to the viewer.

“I am curious to see if people will feel welcome to enter the space. I’m very aware of the crowd. From one piece to the next I interact more or less with them. For example, in my performance work Warmblood I had very little interaction with the crowd—it was about that strong bond with the horse on the ground and interacting with the horse. Where with other performances I focus more on connecting or engaging with the audience.”

An awareness of the audience makes sense for an artist whose background is rooted in theatre. Yet while Sabourin toys with the traditional relationship between the artist and the audience, she also upends narrative expectations.

Vicky Sabourin, “Danse Macabre” (installation view), 2016. Image courtesy L’Œil de Poisson. Photo: Charles-Frédérick Ouellet.

Vicky Sabourin, “Danse Macabre” (installation view), 2016. Image courtesy L’Œil de Poisson. Photo: Charles-Frédérick Ouellet.

“When I started studying art, I was still really fascinated by mythology and all of those stories from my childhood, but in my art I am focusing on one very thin slice of a story. Even the way I perform, which is usually durational, there is never really a beginning or an end—it’s continuous.

“I’m interested in telling stories that aren’t necessarily a tale that everybody knows, or don’t have a clear progression, like a movie or like a play, but still expresses something that we’re familiar with, or something that resonates with all of us.”

Vicky Sabourin will have two projects at the Musée National des Beaux Arts de Québec as a part of the Québec City biennial, Manif d’Art 8: she will be included in a group show at the MNBAQ from February 17 to May 14, 2017, and have a solo exhibition at the Galerie Famille in the MNBAQ opening November 27 as part of the biennial’s programming.

Vicky Sabourin performing at the opening of “Danse Macabre” (2016).

Vicky Sabourin performing at the opening of “Danse Macabre” (2016).