A view inside Donald and Melania Trump’s Manhattan apartment. Photo: Sam Horine.

A view inside Donald and Melania Trump’s Manhattan apartment. Photo: Sam Horine.

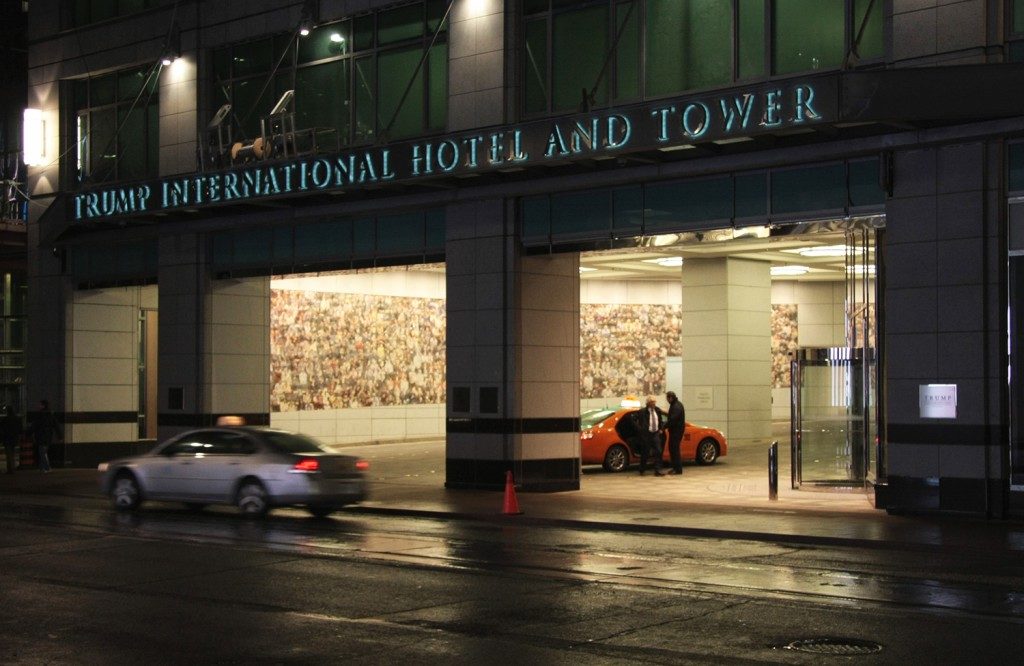

At Trump International Hotel and Tower in Toronto, the Trump Organization’s website boasts, “you will find every detail exceeds all expectations.”

And this blanket statement—though saturated in US President-elect Donald Trump’s characteristic hyperbole, which has extended beyond self-parody and is now entering the dreaded stage of “normalization”—might in fact have some truth to it.

Much has been made of Trump’s taste, or lack thereof. Though he has existed in the public imagination for nearly four decades, evidence of his interests or tastes in regards to art are scarce. We know he knows the word, at least, because the book attributed to him, Trump: The Art of the Deal (1987), uses “art” in its title. (But then again, maybe that was a contribution from Tony Schwartz.)

At Trump’s three-storey penthouse apartment in Manhattan’s Trump Tower, a gaudy marble-and-gold rococo travesty lit by candelabras, there’s no art on view, except for a reproduction of Renoir’s La Loge in Melania’s office, and various depictions of Greek gods. “Part of the beauty of me,” Trump once explained, “is that I am very rich.”

One would expect to see a similar display of garishness at the properties that bear his name, but for the two in Canada—the aforementioned Trump International Hotel and Tower in Toronto and Trump Tower in Vancouver—it turns out that such expectations are wrong. Many of the artworks come from artists whose own political views are in opposition to all that Trump stands for.

Though Trump is a shareholder in some of the buildings that bear his name, including those in New York, Las Vegas and Chicago, he has limited involvement in many Trump properties, and very little decision-making power in regards to what art is housed in the franchises embellished with his name. The buildings themselves have been sites of protest, and the Vancouver Women’s March event on January 21 includes a stop at the Trump building on West Georgia Street.

Stephen Andrews, a small part of something Larger, 2011. Mosaic.

Stephen Andrews, a small part of something Larger, 2011. Mosaic.

A 500,000-piece mosaic themed on multiculturalism, created by Stephen Andrews, a gay artist who has lived openly with HIV for decades, adorns the covered driveway leading into Toronto’s Trump Tower. Andrews is an artist whose politics are sure to offend the delicate sensibilities of Trump’s vice-president, Mike Pence, who believes in the efficacy of electro-conversion therapy for LGTBQ+ people.

There’s also the Michael Snow–designed Lightline, a streak of light reaching to the Tower’s 65-story peak. When it was installed in 2012, the Toronto Star called it “a mix of bold flashing colours with a weird thing on top,” noting that “the skyscraper light appears to be the manifestation of Donald Trump himself.” Later that same year, Toronto Life reported that the artwork was malfunctioning, but conceded that at least it wasn’t “demanding its money back,” as its investors were, “or smashing on the street below,” as the building’s antenna and glass panels had. A 2013 profile of Snow noted that “Trump and Snow actually have a lot in common: unshakable ego, wilful disregard for public opinion and a knack for stoking controversy.” It’s a comparison that Snow would now likely contest.

When I asked Andrews how he felt about his work being permanently installed in a building bearing the Trump name, he told me, “When I took the commission, his presidency was unimaginable. But here we are. I completely oppose all that Trump now stands for.”

“The relationship between artists and patrons is a long and storied one,” Andrews points out. “One imagines that the relationship between Rockefeller and Rivera was a troubled one. Certainly the Church and Caravaggio had issues. The Medici were the mafia of the Renaissance.”

Stephen Andrews, a small part of something Larger (detail), 2011. Mosaic.

Stephen Andrews, a small part of something Larger (detail), 2011. Mosaic.

When a small part of something Larger was commissioned in 2011, the property developers (themselves Russian-Canadian immigrants) asked for it to take the theme of multiculturalism. Andrews explains, “This was a public art commission—the payola developers give to the public to build things that contravene city-zoning regulations—and the brief, as developed between the developer and the City, was, interestingly, on the subject of immigration. The developers had immigrated to Canada and wanted to have a work that spoke to the multicultural nature of the country.”

It’s an unexpected theme to find in artwork at a Trump building, when many of the President-elect’s campaign policies and platforms have been routinely criticized for espousing xenophobic and white-supremacist attitudes. “We all have our contradictions,” Andrews says. “When I got the commission, I was happy to have the budget to produce a work on that scale and make a little money. The Trump name was problematic, but I thought at the time a lesser evil. It was an opportunity, and frankly,” he jokes, “there ‘ain’t nothing going on but the rent.’”

“There is a little bite into the hand that feeds if you think about the theme of immigration and the source images for the work itself,” he continues. On where he found inspiration for the mosaic image, he says, “I was looking for a place in Toronto where the city performed the ideal of itself. It turned out to be a Raptors game. There in the audience you will find a picture of what the country imagines itself to be. People from all walks of life and from everywhere getting along. All cheering for the same team, unlike the divisiveness espoused by Trump et al.”

When visitors to Trump International see his work, Andrews hopes that it will cause them to “question what part we all play in this.” “Before anyone starts throwing stones,” he says, “I ask them to look at their mutual funds or stock portfolios to see how clean the sources of their revenue are. We are all caught in globalization’s web. Negotiating one’s way through is fraught.”

Stephen Andrews, a small part of something Larger, 2011. Mosaic.

Stephen Andrews, a small part of something Larger, 2011. Mosaic.

It’s not just artists and unit owners seeking to distance themselves from the Trump building in Toronto. After years of legal and construction troubles, the chairman of Markham-based Talon International Development Inc., which owns Trump Tower in Toronto, sought to have the Trump name removed from the building. It’s now up for sale, for a cool $298 million.

Unlike Toronto’s Tower, which was built from the ground up, the yet-to-open Trump Tower in Vancouver moved into an existing structure that was designed by the late Arthur Erickson, an openly gay architect. Miriam Aroeste, a Mexican-Canadian artist based in Vancouver, has 180 works in different sizes and mediums in the property, including paintings and a stainless-steel sculpture for the residential lobby.

“When I started working on this project,” Aroeste says, “Trump was not even a candidate.” He had not yet declared that the artist’s home country sends sex offenders to work in the US, or that he wanted to build a wall along their countries’ shared border. The notoriously misogynistic “locker-room talk” video had not yet been released, and Trump hadn’t yet been publicly accused of sexual misconduct by over a dozen women. “I have my own views and preferences and my personal politics don’t align with him as a leader,” Aroeste says. “I am very proud to be Mexican-Canadian and a female artist. In terms of the art itself, I decided to totally focus on the artistic side and create paintings filled with messages of love and inclusiveness.”

In an Instagram post showing a short video of one of the artworks installed, one of Aroeste’s assistants, Tyler Goin, wrote, “Although it could be considered social suicide to do something for Trump, at this point I believe I have to own up to it—as it is such a valuable experience to do something beautiful and for the right reasons in the face of adversity and in good company. I hope that everyone is reminded of the delicate approach to dealing with one another, to understand why things happen, to act for justice and to know when to forgive.”

The Vancouver hotel, owned by the Holborn Group, a private real-estate developer, will be managed by Trump’s company, which is also overseeing the building’s interior design. It will contain Canada’s first Mar-a-Lago Spa by Ivanka Trump. Trump’s daughter, an art collector whose tastes fall more in line with the trends of this decade, has met scrutiny in recent months from the artistic community. A group of artists launched the @dear_ivanka social-media accounts, which take the heiress to task for her hypocrisy and role as advisor to her father, and some artists she collects have been vocal in their desire to disassociate from her. Richard Prince even went so far as to disavow authorship of a portrait she commissioned him to make.

The City of Vancouver is taking pains to sever connections to the Trump brand. Mayor Gregor Robertson wrote a letter to Holborn Group CEO Joo Kim Tiah, saying, “Trump’s name and brand have no more place on Vancouver’s skyline than his ignorant ideas have in the modern world. As Mayor, it is my hope that you and your company will work quickly to remove his brand and all it represents from your building.”

Tiah has said in a previous statement that “Holborn, a company that has contributed immensely to the growth of Vancouver, is not in any way involved in US politics. As such, we would not comment further on Mr. Trump’s personal or political agenda, nor any political issues, local or foreign.”

In their end-of-year article about the “20 Most Powerless People in the Art World: 2016 Edition,” Hyperallergic placed “Architects and Designers Who’ve Worked on Trump Buildings and the Trump Brand” at number 19: “[W]hat once may have seemed like a harmless contract with a buffoonish businessman is now a charged record of working with the most divisive political figure in recent memory—one whom huge swaths of the design field have repudiated. Advice to past Trump designers: purge him from your portfolio.”

Perhaps some of the best advice comes from Trump himself. The Art of the Deal offers such sage business advice as, “Think big,” “Fight back” and “Have fun.” Active and direct methods of daily resistance are required to slow the momentum and decrease the power of fascist, oligarchic rule. But there is perhaps no more pleasurable way of motivating acts of noncompliance than by entering the opponent’s territory under the guise of art. It worked for the Trojans and their statue of a horse.