1. Valérie Blass at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal

Here is an exhibition that left me feeling so excited that I found it difficult to express the experience in words. Given that expressing such experiences in words is supposedly part of my chosen profession, admitting this lack has prompted some shame on my part. What I can say is that I enjoyed the exhibition immensely. Blass’s sculptures are smart while also being intensely physical, and they are witty while also being intensely humane. I find that a lot of good contemporary art out there makes me feel terrible about life. And there is a lot in life to feel terrible about, admittedly! But Blass’s work, in a much rarer mein, manages to be good (okay, great) contemporary art that makes me feel good (sometimes even great) about life. That effect is likely more about me than about what she brings to the table, but whatever alchemy is proceeding when I view her works, I am grateful for it.

2. “William Kurelek: The Messenger” at the Art Gallery of Hamilton (also organized by and shown at the Winnipeg Art Gallery and the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria)

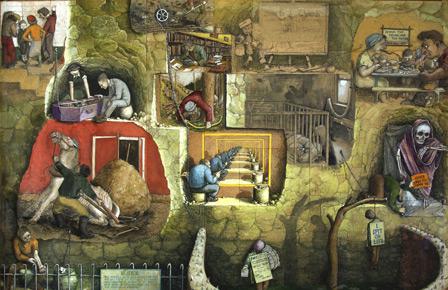

I grew up cherishing a copy of William Kurelek’s A Prairie Boy’s Winter in Winnipeg and Calgary during the 1970s and 1980s, so let’s just say I was a fan of this show before I even laid eyes on it. It stands to reason, therefore, that this exhibition could have easily rested on the late artist’s well-known laurels and done little to challenge or enlighten viewers. Happily, the curators involved—the WAG’s Andrew Kear, the AGH’s Tobi Bruce and the AGGV’s Mary Jo Hughes—put together a complex view of a complex man. It was a horrible, thrilling treat to see works from Kurelek’s most depression-darkened years in the same frame as his over-sweetened “potboilers” (of which many Prairie Boy works were an example). Throughout, I continued to admire Kurelek’s precisely illustrative style, fine colouration and juxtaposition of grand themes with “humble” Canadian settings. More than that, though, I was struck by his tendency to stick to his guns in his most personal work; in such images as Mendelssohn in Canadian Winter and The Dream of Mayor Crombie in the Glen Stewart Ravine, there is never a sense (as there is in so much contemporary art) of “C’mon Bill, tell us what you really think!” As much as my personal code of faith and morals might diverge from Kurelek’s, I really appreciated his tendency to put his views out there, as well as his compulsion to go beyond aesthetics and demonstrate (rather than obfuscate) his struggles with the shifting contemporary world, various black moods and the eternal proviso that “in the midst of life, we are in death.” A strong virtual version of the exhibition sealed the deal in terms of putting this on my best-of list.

3. Are You My Mother? by Alison Bechdel

First-person criticism can still be a contentious form in some quarters, being regarded as unprofessional, distracting and unhelpful, among other problems. And the longer I write and edit material that may be considered by some people to be criticism, the less I feel I really know about what art criticism should be—let alone its subject matter, art. So it was heartening to read Alison Bechdel’s terrific graphic novel Are You My Mother?, released this year. In large parts of this book, Bechdel struggles with her tendency to write in a first-person form—the memoir. Bechdel’s mother (the subject of the book) disagrees mightily with memoirists and their ilk, which lends no small amount of psychodrama to a tale already threaded through with years of therapy sessions, readings on child development, and other painful family relationships. (Read Bechdel’s excellent 2006 release Fun Home for more on the latter.) As I learned at a Toronto talk by the artist, the image production for the book is also extremely involved and intense; I loved the fact that Bechdel took time to reproduce details of the posters on her therapists’ walls. (There’s a form of art that’s both over-examined and under-criticized, to be sure.) I also love that she got through to finishing the book, doubts included—because that first-person form can often be for me (if not, quite understandably, everyone) a helpful and powerful one to read, process and reflect upon.

Leah Sandals is Canadian Art‘s online editor.