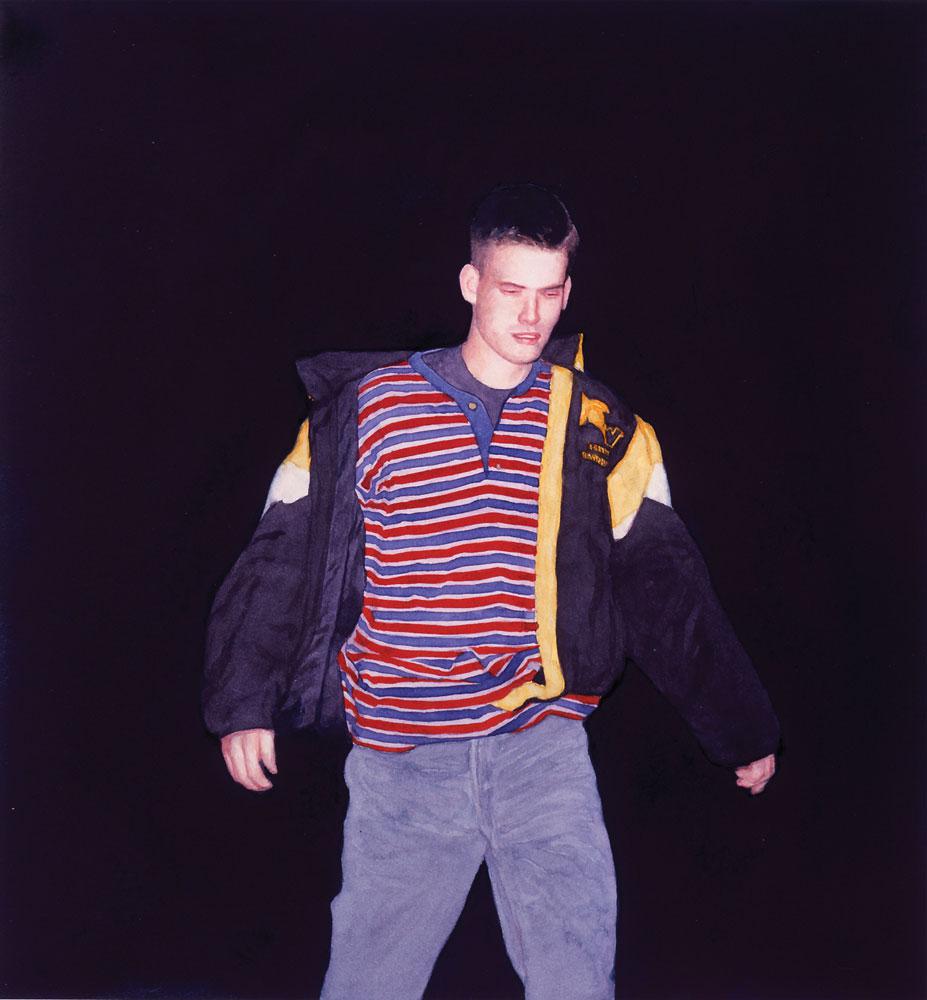

A long-haired man in blue jeans does a handstand on a high, rocky ridge in the middle of a mountain range. A bald fellow in a Hawaiian shirt stands on a boat deck, holding a glass of vodka and gazing at a hazy sunset over an expanse of calm sea. A rain-sodden camper in a forest clearing crouches close to his small metal stove, a Pontiac Sunfire parked behind him.

Much has been written about Tim Gardner’s interest in depicting human beings and their popular-culture baggage within majestic natural environments. His realistic watercolours are frequently based on—but differ in important ways from—snapshots or found photos, and seem to query the conventions of representation and the aesthetics of vernacular photography. At the same time, they explore the tropes of masculinity, including drunken partying, team sports, brotherly love and strenuous outdoor activities. Critics often comment on Gardner’s juxtaposition of the banal with the sublime and, yes, this West Coast artist frequently plays mountain landscapes, dusky seascapes and towering forest scenes off the people and paraphernalia of the everyday: beer bongs and hot-dog roasts, backwards baseball caps and dumbass T-shirts, shopping malls and parking lots filled with SUVs. At this point in his career, however, Gardner has developed an aversion to the words banal and sublime. The first is too pejorative, perhaps, and the second too freighted with the history of Romantic art, a subject that inevitably wedges itself into the critical dialogue surrounding his work. Analogies have been drawn between his depictions of solitary figures overlooking awe-inspiring natural vistas and Caspar David Friedrich’s 1818 oil painting, Wanderer Looking Over the Sea of Fog. But Gardner’s art is not really married to the Romantic tradition, he says, pointing out that he also locates his human subjects in “smoggy city scenes or the interiors of museums.” In skateboard parks, beside backyard swimming pools and outside neon-lit resorts, he might also add. Nature here is reconfigured; Romanticism, reconsidered. Even his unpopulated landscapes declare evidence of human presence: a paved road, a nylon tent, tree stumps.

Gardner is dissuaded, too, by the word sublime’s mushy-minded ubiquity, its vernacular promiscuity. “It can be used to describe anything from the vastness of the universe to a tasty dessert,” he observes. I suggest “grandeur” as a way of defining the mountain scenes that, other subjects notwithstanding, command many of his recent watercolour paintings, but he’s not sure about that word either. Still, the contradiction between low culture and high nature—low as in small, ordinary, impermanent, and high as in majestic, soaring, unassailable—persists in his work. High, too, as in thousands of metres above sea level, high as in challenging to ascend, high as in the furthest metaphorical remove from the terms of human existence. In Gardner’s art, the immensity of the mountain subject speaks to a geological order of mass and time, in contrast to that of our fleeting, inconsequential, individual lives.

But that existential reading does not quite nail it for him either, because in his view, the comings and goings of ordinary folk are of consequence, and, more importantly, so is their relationship with the natural world. Whether Gardner’s figures are enthralled with or oblivious to their surroundings, his art argues an ineluctable bond between the great Out There of mountains, ocean and forest, and the niggling In Here of psyche. It’s a theme with firmly autobiographical origins. “My dad is a geographer and my mom was a family therapist,” he says. “This contrast or division or balance between humans and the landscape is basically my critical issue. It defines who I am personally and how I relate to the world.”

Gardner’s father Jim, an academic whose area of specialization is mountain geomorphology, is also and not incidentally a skilled mountaineer. He took his three sons on hiking and climbing expeditions in the Canadian Rockies throughout their childhood and youth, and that experience was clearly formative for the nascent artist in the family, the quiet middle child with his impressive talent for drawing. Jim Gardner and his brother and parents, Tim Gardner’s paternal grandparents, were actively involved in the Alpine Club of Canada in the middle years of the 20th century. An amateur athletic association founded in 1906, the ACC created a constitution that includes not only the promotion of mountaineering across the country but also “the preservation of the natural beauties of the mountain places and the fauna and flora in their habitat.” Not surprisingly, environmental themes can be read into much of Gardner’s recent work.

Gardner lives with his wife, Veronica Schreiber, and their two young children on a rural property about 20 kilometres north of Comox, on Vancouver Island. Their home lies between sites of outdoor activity—that is, between the beaches of eastern Vancouver Island and the mountains that run up its spine. Their large, sunny yard, whose western perimeter is drawn by a curve of the Oyster River, is enlivened by swings hanging from tree branches, a playhouse, two chicken coops and a large and flourishing vegetable garden. Near Gardner’s studio, a huge old stump, some four feet across, mutely symbolizes the old-growth forest that surrounded the Comox Valley until the late 19th century. Some of the tallest Douglas fir trees in the world once stood where small farms, bedroom communities and recreational properties have established themselves. A powerful sense of the nature-culture interface, of the human occupation and exploitation of the temperate rainforest, continues to condition life in this place. Black Creek, the nearest community to Gardner’s home, grew out of a couple of logging camps in the early years of the 20th century. If, as viewers, we project ourselves into, say, his life-size pastel portraits of tree planters backgrounded by heavily forested mountains, the understanding is that, unseen behind us, are logging roads and clear-cuts. “There’s not any virgin forest out here,” Gardner says, gesturing to the woods across the river. “It’s all been replanted.”

When Gardner alludes again to his family history of mountaineering, he mentions that his father’s parents were friends with Walter J. Phillips, the English-born Canadian painter, printmaker and outdoorsman who was an influential presence at the Banff School of Fine Arts, now the Banff Centre, during the 1940s. Phillips, whose landscapes include a number of Rocky Mountain scenes, had a posthumous impact on the young Tim Gardner. “I spent a lot of time looking at his work on the walls in my grandparents’ house, including numerous prints and a watercolour of Mount Temple,” he recalls. Something of Phillips’s application of the English watercolour tradition to Canadian alpine subjects reverberates in Gardner’s art. The watercolour landscapes of Winslow Homer and John Singer Sargent have also influenced him.

Still, a strange incongruity exists between many of Gardner’s subjects and his choice of medium. Watercolour’s seeming delicacy and its associations with gentility create a paradox when considered with the figures or activities depicted. This was especially true early in his career, when he focused on images of college-age Canadian guys boozing and carousing their way through their extra-curricular life, shotgunning beer at local parties or hamming it up in liquor stores on road trips to Miami Beach or Las Vegas. While at graduate school, at Columbia University in New York, Gardner grappled with large-scale figurative paintings in oil, working from snapshots of this booze-fuelled, white-guy world featuring his older brother surrounded by friends and roommates. Although he was dissatisfied with the oil medium, the subject matter endured through his segue into the unlikely realm of small-scale watercolours. “When I was doing those pictures of all those guys partying, in oil painting, it was just too over-the-top masculine,” Gardner says. “I like the contrast between the watercolour medium and the subject matter—kind of a good tension.” Watercolour suits his purposes and his disposition. He enjoys its intimacy and immediacy, and is not intimidated by its unforgiving nature, its transparency, its refusal to accommodate errors. “You can mess up a whole painting with one mistake, but that’s what I like about it—that element of risk.”

There is also, in Gardner’s small paintings on paper, a general resistance to, even a defiance of, the art world’s obsession with spectacle, with museum-scale forms and materials that physically dominate the viewer. His beautifully rendered images invite our close and quiet attention while at the same time staking out an oppositional position to post-studio practice and the phenomenon of deskilling.

Deskilling never figured in Gardner’s career arc: he always drew and painted realistically and with great facility. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, he appeared to transition from gifted graduate student at Columbia to internationally acclaimed artist—represented by prestigious dealers in New York and London, widely exhibited and collected, praised in art journals and the world press, invited to assume a much-publicized residency at Great Britain’s National Gallery followed by a solo exhibition there—with both speed and ease. Since then, it looks as if he has settled into an enduring and productive relationship with the demands of both cultural institutions and the marketplace, regional, national and international.

I tell him he seems never to have gone through that “emerging artist” phase, meaning the probationary period of exhibiting in alternative galleries and artist-run centres before being championed by curators, dealers and collectors. He replies—and is this a problem of semantics?—that artists “never stop emerging.” He is in a constant state of creative evolution, much of it marked by self-questioning and uncertainty, but also by an intuitive sense of what imagery will work for him. Still, I argue, he seemed to land in the art world fully fledged. His first US solo show, at 303 Gallery in New York in 2000, sold out. “I was just in the right place at the right time,” he says. “When I went to Columbia, figurative painting was really popular, work on paper was becoming popular, and the whole art world was obsessed with youth.” He adds that, yes, people were excited by his treatment of guys in their late teens and early twenties endlessly partying, but for him personally, it was all about “the idea of masculinity.”

His art continues to follow an autobiographical and gender-role querying path, and the scenes that he psychologically projects himself (and, by extension, us) into have evolved and matured. He has explored scenes of adult family members dining under leafy bowers in outdoor restaurants, married couples seated in city parks or on lakeside logs and men hiking or skiing with their young children. At the same time, his watercolours frame images of tiny, solitary humans within scenes of immense nature, poised at the top of a ski slope or on the crest of an ocean wave. Conversely, these men may be depicted sleeping in a bus or car or on the deck of a ferry, unconscious of their glorious surroundings. Since settling on the West Coast, Gardner has been painting the ocean as seen from vantage points in Vancouver and Victoria, and from ferries crossing the straits of Georgia and Juan de Fuca. Mount Baker, the third-highest mountain in Washington State, often floats above the horizon. Visible from much of Metro Vancouver, Greater Victoria and Seattle, it is the region’s most conspicuous natural formation; in Gardner’s art, its immense height, volcanic shape and snow-covered slopes conjure up Hokusai’s 1830s series of woodblock prints, One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji. It both connects us to place and transports us heavenward.

Gardner’s experiments with the atmospheric effects of dusk and sunset and silvery moonlight are strangely provoking to our assumptions about fine art aspirations and popular taste. In recent watercolours that depict lifeguard huts on sunset beaches or solitary surfers riding moonlit waves, he intentionally walks the tightrope between criticality and kitsch, between historic reference and romantic cliché. He sees this as another one of his challenges, along with his unlikely media, watercolour and pastel, and their associations with amateurism and unenlightened art making. “Pushing the line,” he calls it. The line between gentility and masculinity. Painterliness and precision. Banality and, well, the sublime.

This is a feature article from the Winter 2014 issue of Canadian Art. To see more works by Tim Gardner, visit canadianart.ca/gardner. To read more from this issue, visit its table of contents. To read the entire issue, get a copy on newsstands, the App Store or Zinio until March 14.