The two of us were born of the same streets, led by hand through the intersection of Bloor and Bathurst in Toronto, from the Black bookstores to the hair salon to the roti shop. This was a meeting place of Black culture, seeded in the wave of Caribbean emigration from and after the 1960s. The community shared a utopian view of a liberationist future for all African peoples. Here, they were as radical as they could imagine.

The two of us were children of this revolutionary thinking. The 1970s, 1980s, student unions, communist manifestos, weekly newspapers, feminist associations, Black queer love, poems. Our view from there looked to a horizon. To dream and unmake dreams was this life, we learned. We were parented into liberation. These streets and our bodies, the community! We zigzagged in and through history, dizzy with a view of the future.

This feature holds still such fragments of history and their liberationist ethic, refracting them across streets and the borders of this place called Canada, inviting promiscuity across space and time. The recent weeks of white supremacist violence against Black people—prominently staged in policing, health and labour—led us to curate this. Even so, we intend to convey modes of Black life from a parallax view, irreducible to images of brutality and death. Further, we push against mainstreaming that deradicalizes justice and obscures the horizon in sight.

This piece offers an honest conversation among Black women arts workers, art historians, poets, organizers, scholars and activists. They have long worked toward a future that only now disorients many in the present “event.” We invited contributors to reflect on the themes: Black history and its erasure in Canada, the “unthinkable” nature of Black revolt (Michel-Rolph Trouillot), the saturation of Black death in the visual field, and the taste, smell, feel and style of liberation. Then, we set their separate pieces beside one another.

The form of this piece is meaningful. It is not unlike the messiness of ourselves, solidarity, language and artwork. What you will read is a practice of intention, turned into a conversation of fragments, a fragmented exchange. We ask that to join, readers do a few things. We encourage you to read each contribution on its own terms, while holding the others, and more, within them.

We also ask that you attend to this with care. The calendar is not the measure of engagement. There is no guilt in setting this aside. Read in and across fragments as you wish. We welcome your return.

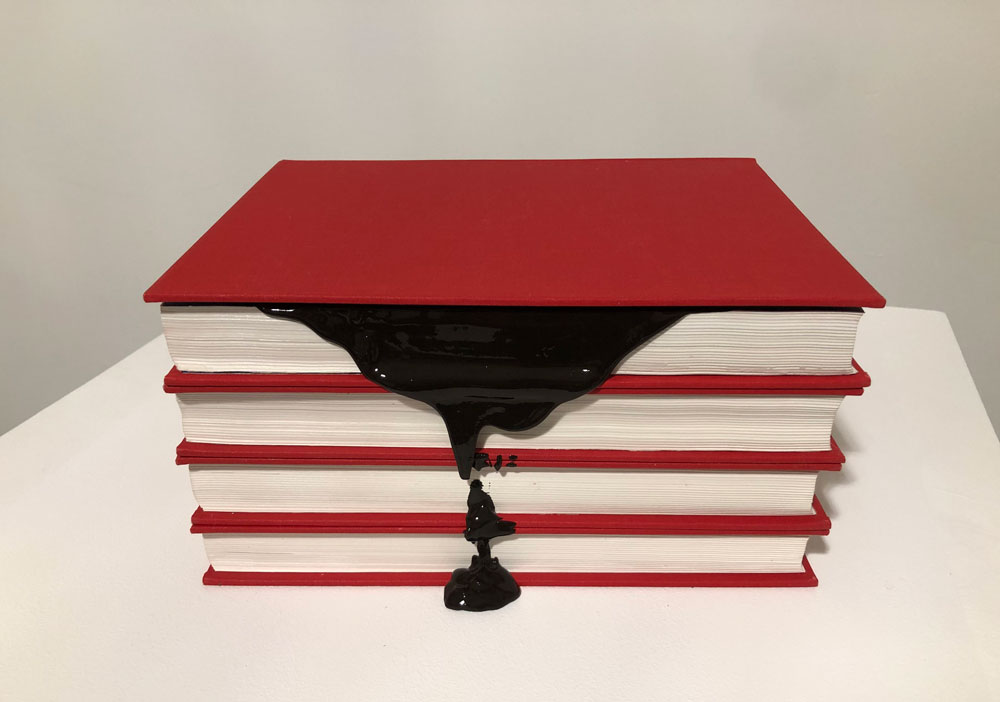

Chantal Gibson, Redacted Text, 2019. Altered Book, Canadian Encyclopedia (3 Vol), liquid rubber. Photo: Chantal Gibson. Courtesy the artist.

“An encyclopedia must undergo revision if it is to remain current and if it is to hold its place as a reference point amid the rapid proliferation of knowledge.” From the preface to The Canadian Encyclopedia, 2nd edition. Hurtig Publishers Ltd. Edmonton, Alberta, 1988.

Chantal Gibson, Redacted Text, 2019. Altered Book, Canadian Encyclopedia (3 Vol), liquid rubber. Photo: Chantal Gibson. Courtesy the artist.

“An encyclopedia must undergo revision if it is to remain current and if it is to hold its place as a reference point amid the rapid proliferation of knowledge.” From the preface to The Canadian Encyclopedia, 2nd edition. Hurtig Publishers Ltd. Edmonton, Alberta, 1988.

El Jones

So often in this work, we keep ourselves alive thinking, “someday I’ll be proven right.” But when we are right, amnesia sets in. People pretend they were with us all along. They forget what they said and did. They tell us it was something in us, something we did wrong (“I agreed with your issues, just not with your tone/tactics”). So in this moment, as things we have been fighting for are suddenly being taken seriously, I can’t forget the violence Yusra Khogali faced when she called Justin Trudeau a “white supremacist terrorist.” People denounced her and demanded she be punished, exiled and silenced—those same outlets today talk about Trudeau’s 21-second pause. I can’t forget how, after a 1995 incident, Burnley “Rocky” Jones was sued by a police officer, and the same institutions praising him today ignored whether he lived and died in comfort. We talk about structural injustice without the people who experience harms and who are left behind, as the struggles they sacrificed for are watered down through false claims, appropriation and co-opting.

One of the brothers in prison said to me, “I don’t see how we can go back to believing in prisons the way we did before.” Reanimating what abolitionists said long before this moment of protest, he suggests that as the world cracks apart, we can imagine and work to bring different futures into being. I never in my life thought I would see a police station burn; the thought now keeps me warm.

On Sunday, an elder of Africville drove me for hours around the original boundaries, pointing out the landmarks, the places Black people walked and prayed and worked and birthed and died and were removed. In the avalanche of protest, media, writing, speaking, those hours felt revolutionary. Tracking the ghosts of that land with the still-living, unbeaten and unforgotten powerfully oriented me back within what we are still struggling for. So many of these wounds are open in our communities. Sometimes transformation looks like going back.

El Jones is a poet, professor, community advocate, journalist and prison abolitionist from Halifax. She is a co-founder of the Black Power Hour, a radio show collective with prisoners, on CKDU 88.1 FM. Her book of poetry and essays about state violence, Canada Is So Polite, is forthcoming in 2020.

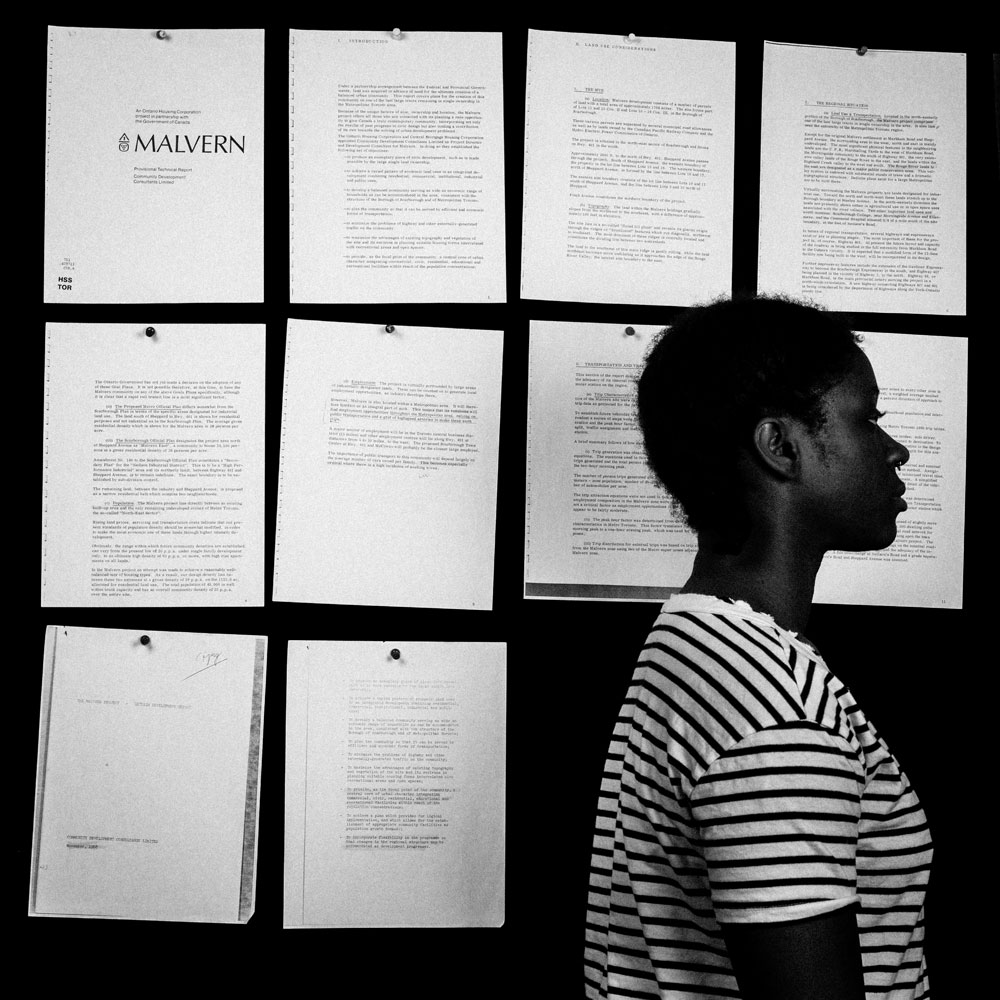

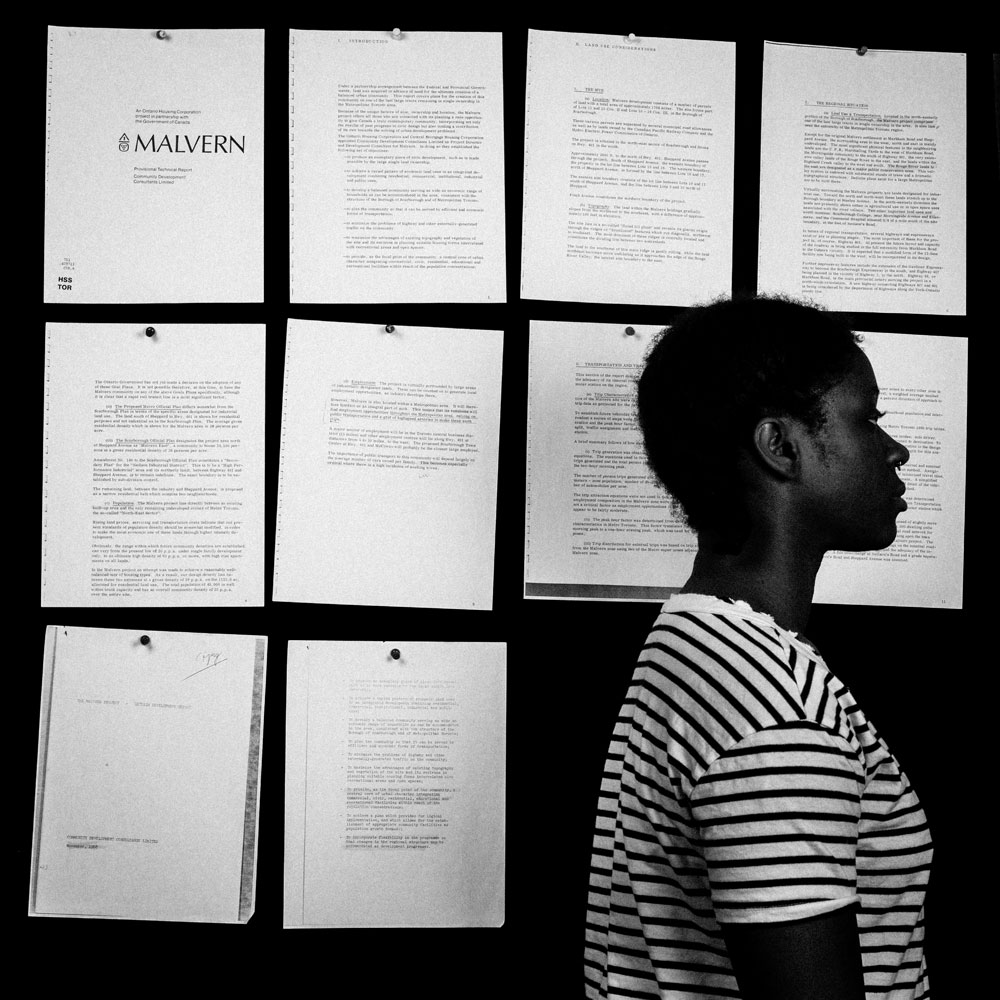

Anique Jordan, Malvern, 2019. Archival pigment on canson baryta paper. 32.75 x 32.75 in. Courtesy the artist.

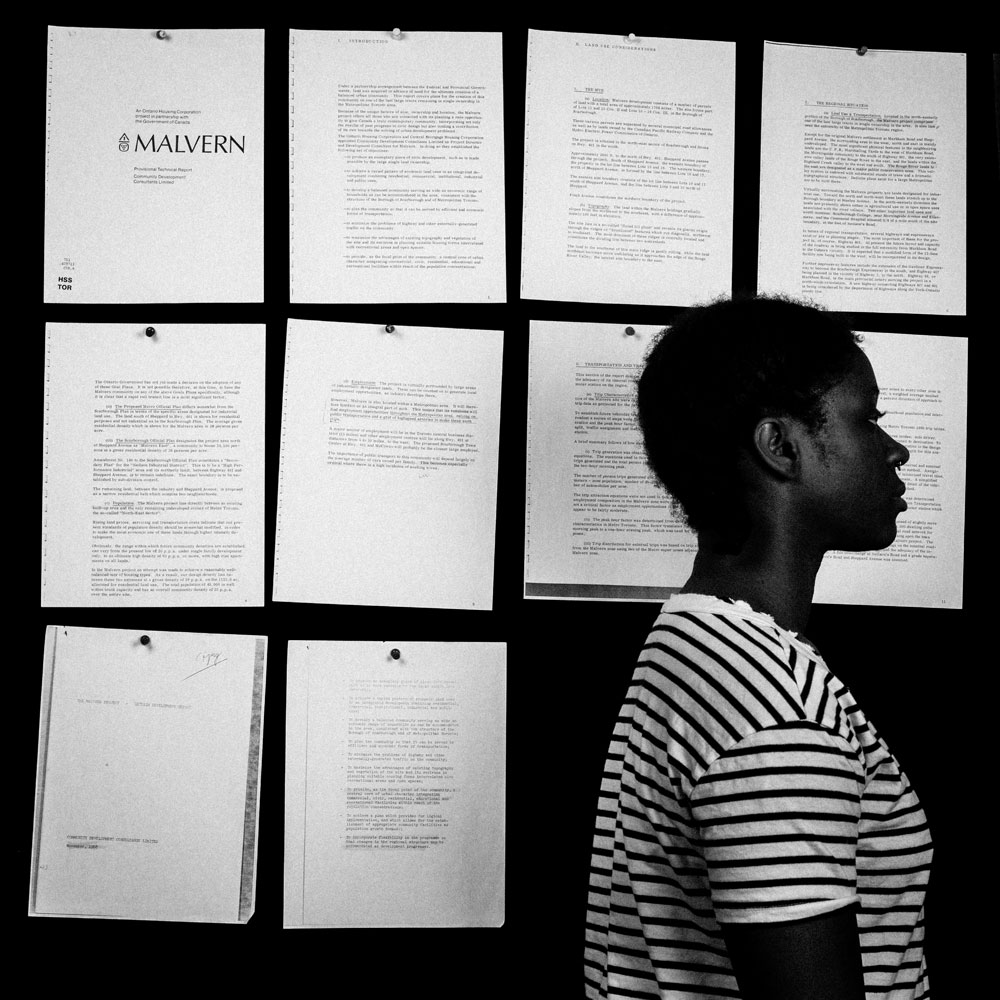

Anique Jordan, This place is no good, 2019. Archival pigment on canson baryta paper. 32.75 x 32.75 in. Courtesy the artist.

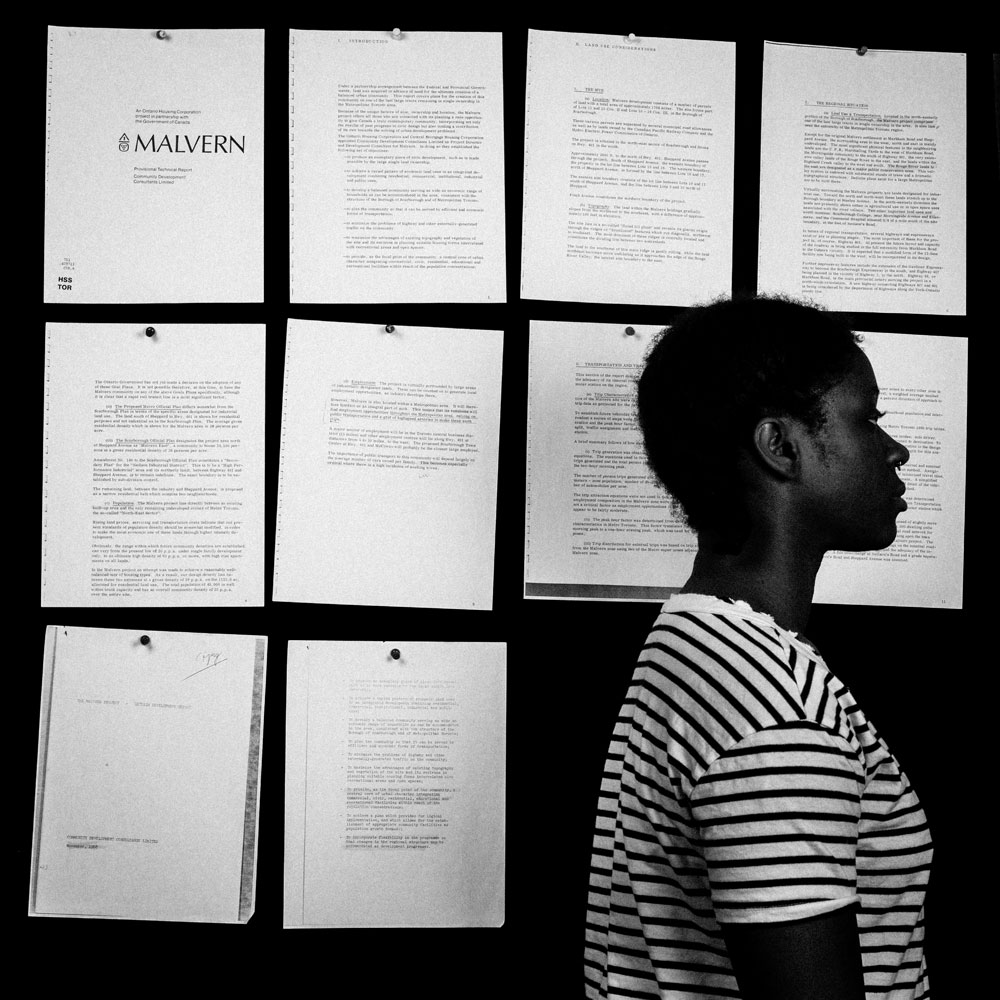

Anique Jordan, Notes, 2019. Archival pigment on canson baryta paper. 32.75 x 32.75 in. Courtesy the artist.

Anique Jordan, Carding, 2019. Archival pigment on canson baryta paper. 32.75 x 32.75 in. Courtesy the artist.

CHRISTINA SHARPE

“There’s time enough, but none to spare” (Charles W. Chesnutt). In the interregnum of state violence and insurrection, something momentous appears to be happening everywhere. In the protests’ intensity and reach, spread and velocity, we are experiencing an uprising. People are clearing a space into which something new is being summoned. Something Black people imagine daily. Something like “breathing.”

For 10 days and counting, and in the midst of a global pandemic, the effects of which have disproportionately harmed Black people, thousands of Black people have nevertheless gone into the streets to face the triple threats of COVID-19, the violence of care/no care if infected and the always-present threat of police violence—police being already, itself, a name for violence. Yet people remain in the streets demanding an end to policing and all that it sustains and is sustained by it. They are manifesting that care is shared risk and abolition is a synonym for love (Saidiya Hartman, 2020). They are refusing the unbearable life, rejecting the dead future.

Static monuments to a global white supremacy are coming down: one protestor breaks the right hand off a statue of Louis XVI in Louisville, Kentucky; in Bristol, England, a crowd topples Edward Colston and throws him into the River Avon; in Richmond, Virginia, a group of young people pull down a monument to a Confederate general (this is repeated multiple times, in multiple cities); in Brussels, Belgium, a crowd gathers around the statue of King Léopold II chanting “assassin,” “réparations.”

The chorus is speaking (Hartman, 2019). Other ways of living are possible. They’re being made right now.

The chorus have taken the present into their own hands (Michel-Rolph Trouillot).

Christina Sharpe is professor of humanities at York University. She is the author of Monstrous Intimacies: Making Post-Slavery Subjects (2010) and In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (2016). She is working on two forthcoming monographs: Ordinary Notes and Black. Still. Life.

Kara Springer, Untitled, Dover Beach, 2015. Courtesy the artist.

Kara Springer is an artist currently living between Toronto, New York, and Houston, whose practice is particularly concerned with armature—the underlying structure that holds the flesh of a body in place.

Kara Springer, Untitled, Dover Beach, 2015. Courtesy the artist.

Kara Springer is an artist currently living between Toronto, New York, and Houston, whose practice is particularly concerned with armature—the underlying structure that holds the flesh of a body in place.

Denise Ferreira da Silva

Any imaging of otherwise in this world requires contending with the scene, the scene of violence, and with that which captures the when, how and where a black person was killed by a police officer. The creative work returns to the person and to those who knew and love them. It must face squarely the ethical-political challenge of working with the visual nowadays, which is to find the balance between visibility and obscurity. Visuality or rather visualizability—being available via social media and accessible through electronic gadgets—seems to have become the main (if not the sole) criterion for reality, which becomes crucial for the ethical-political demands for the protection of black lives, for state accountability and for justice. If that is so, the only way is through these conditions of representation. I mean, the creative move first takes the visualizable as it is, that is, as a twice removed re/composition (at the same time a live streaming, news reporting and documenting) of the scene of violence which only tells us that it happens. It exposes the excess that is the state’s use of total violence, of law enforcement as technique of racial subjugation, while simultaneously removing the black person (the father, the sister, the friend) out of the scene of violence and its visualization. It does so by restoring the dimensions of their existence that the camera cannot capture. That is, the creative move must protect (as an ethical gesture) the black person (keeping her obscurity) in the excess that is the very visualization of the scene of total violence.

Denise Ferreira da Silva is director and professor at the University of British Columbia’s Social Justice Institute (GRSJ). Her academic and artistic works address the ethico-political challenges of the global present. She lives and works on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territory of the Musqueam (xʷməθkʷəy̓əm) people.

Anique Jordan, Kitchen (from the Salt series), 2015. Chromogenic print. 22 x 30 in. Courtesy the artist.

Anique Jordan, Kitchen (from the Salt series), 2015. Chromogenic print. 22 x 30 in. Courtesy the artist.

Christina Battle

How to change what is thinkable when those in positions of power are incapable of thinking otherwise? The unthinkable is tied to a colonial logic that Black and Indigenous artists continually draw attention to, scream out against, see through and see past. Even while we refuse it, as a logic, it’s pervasive.

We know that this logic is sustained by institutions making up the artistic sector: it’s been at the centre of artists’ works, extensively written about and the subject of numerous panel discussions. Yet the logic is a damage that refuses to repair itself. A 2017 study by Michael Maranda drew attention to this ingrained logic by looking at the number of BIPOC in positions of power within artistic institutions. The statistics are bleak, and, since the study was published, I don’t see that much has changed.

As many of the online responses to protests against police brutality reiterate the repercussions of these statistics, BIPOC artists once again bear the brunt of the empty gestures offered by those incapable of thinking otherwise. Even while we’re screaming, even when our bodies are made visible across screens and in the public consciousness, they still can’t think it. I don’t think they want to. We’ve called for them to hire more BIPOC artists in galleries and on faculties—most haven’t—and it shows. Arts councils’ insistence that organizations consider diversity has quickly turned into the adoption of the “right” language with little change.

Wherever it ends up, this moment can help discern who our allies are, and more important, who they’re not. As we take notes and share experiences, we should use this knowledge to expand and construct new systems of our own. We should embrace our histories and generate something new from them for ourselves. It doesn’t need to continue to be unthinkable.

Christina Battle is an artist and researcher based in Edmonton whose work imagines how disaster could be utilized as a tactic for social change and a tool for reimagining how dominant systems might radically shift.

Chantal Gibson, Redacted Text, 2019. Altered Book, Canadian Encyclopedia (3 Vol), liquid rubber. Photo: Chantal Gibson. Courtesy the artist. Chantal Gibson is an award winning writer and artist-educator from Vancouver working in the space where writing and visual art meet.

Chantal Gibson, Erasure Poems(from A Grammar of Lost: Studies in Erasure Series), 2020. Altered book, liquid rubber. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Adrian Bisek.

Chantal Gibson, Erasure Poems (from A Grammar of Lost: Studies in Erasure Series), 2020. Altered book, liquid rubber. Courtesy the artist.

Charmaine A. Nelson

What Michel-Rolph Trouillot called the unthinkable nature of the Haitian Revolution became thinkable as a direct consequence of the heinous violence that was normalized within Dominguan plantation slavery. As Malick W. Ghachem notes, “During their first three to five years of labor in Saint-Domingue, newly purchased Africans died on average at a rate of 50 percent.” You see, the camel’s back was broken and the brutalized enslaved population had, quite literally, nothing to lose. Today, streets all over the world are swelling with protests for George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and Regis Korchinski-Paquet, and we are still haunted by the killings of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland, Abdirahman Abdi, Eric Garner and Philando Castile. Black people live in a constant state of mourning and traumatic shock—no “post” about it. Is this our collective breaking point? Aimé Césaire warned that colonization works to decivilize the colonizer, “who in order to ease his conscience gets into the habit of seeing the other man as an animal, accustoms himself to treating him like an animal, and tends objectively to transform himself into an animal.” The lethal misconduct of the four former Minneapolis police officers reeks of this condition, but the stench is clearly not confined to the US. Is our camel’s back now broken? What the multiple bystander videos captured was a lynching in broad daylight; the impunity with which the foursome operated allowed them to continue about the business of murdering Mr. Floyd in front of an audience. We are weary, we can’t breathe, and I hope that we have reached our limit.

Charmaine A. Nelson is a professor of art history at McGill University. She has published seven books, including Slavery, Geography, and Empire in Nineteenth-Century Marine Landscapes of Montreal and Jamaica (2016). She recently served as the William Lyon Mackenzie King Visiting Professor of Canadian Studies at Harvard University (2017–18).

Kara Springer, Untitled, Lake Ontario, 2015. Courtesy the artist.

Kara Springer, Untitled, Paradise Island, 2017. Courtesy the artist.

Robyn Maynard

We are in a moment of incredible loss, of profound racial violence, of death. We are also, though, in a moment of reinvention, of transformation, of a reconstitution of the social, a challenge to the dominant episteme of Black disposability and expendability, and we are moving into a new, unmarked terrain. This eruption, this revolt, is part of past/present abolitionist movements that transcend national borders.

We are in another moment in which unthinkable changes are, quite suddenly, on the horizon. The notion not just that we should, but that we can #defundthepolice has entered public discourse in a manner I would have thought nearly impossible one month ago. We arrived here through unceasing, if continually transforming, Black revolt. First and foremost, in this moment, this was made possible by those who have taken to the streets from Minneapolis to Bahia to Montreal, risking arrest, incarceration and exposure to COVID-19 to demand a new world. And we arrived here because of the intellectual production and political struggle we have inherited from the radically anti-state, anti-violence work of several generations of Black feminists, incarcerated intellectuals, self-liberated enslaved peoples: all of those whose orientations toward freedom, whose involvement in struggle demanded the seemingly impossible and made no compromises along the way. Divesting in policing, an institution that is not only marked by violence but is itself violence is, to many, unthinkable, even as the idea gains political and public visibility. This is not only a call for budgetary reallocation, even as divesting from punishment and investing in communities is a necessary step toward something closer to freedom. It is a step, one among many, toward a radically transformed social, economic and political reality.

Black liberation will not be contained within the confines of the nation state, nor within the confines of “reform.” It will not feel or taste or smell like what has come before. Yet I believe we will recognize it when it arrives.

Robyn Maynard is a writer living in Toronto and the author of Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada from Slavery to the Present.

Anique Jordan, Outside (from the Salt series), 2015. Chromogenic print. 22 x 30 in. Courtesy the artist.

Anique Jordan, Outside (from the Salt series), 2015. Chromogenic print. 22 x 30 in. Courtesy the artist.

Dionne Brand

Excerpts from A Nomenclature of Everything (forthcoming)

the year was endless, the occipital lobe

driven, maximising propylene yields, how

the recycled was supposed to

to be our carbon, what they saw was to be our seeing

what they saw on the periphery they now see

in the tetravalence in any specific region

the beautiful innocence of those

who live at the centre of empire, their

wonderful smiles, their sweet delight and

and their singular creation of the

word, hope, when I am actually dying

…

all I see is the distress on the faces of the sellers

all I see is the ugliness on the faces of the buyers

the strangest, noisiest night, the rawest market

I notice the small ocean

I notice the oily acid ocean

I notice the crushed brain

do not distort the violence with any water

any love, any laughter, any ax, no ink, or feet

do not

my feet are not delicate, my eyes are not closed

I am only taking a nap from the awful dream

…

I do not have day and I do not have moonlight

I do not believe in time

I do believe in water

…

These people with their crude minds think they can love anything

think they can know the art of the world; all their lives are

spent clawing the grace of things, mangling the sheen of things; collecting the raw instance; they lift their arms and displace millions, why am I on earth with them

…

The general hospital asked me to donate this ugly heart of mine

I said, no one should have it

let us leave it at that

no one should have it

…

The monsters are talking all over the world,

they are talking an insane language, they are

multidisciplinary and multilingual and we are finding

it hard to move our limbs again

they are phagic and happy, the government sent me the results

…

The racial intrigues, spinning off local narrations, the

intrigues of stasis, the layers of inconceivability, intractable narrations, unforgiveable narrations

may cause at any moment explosions that I suppress but they detonate nevertheless in me

in me the duration of stones

I owe my beating heart a debt for its endurance, its persistence, its

profound knowledge that is beyond any capacity to know its amplitude for taking these detonations and insisting on living on

I interpret small signs of its breathless career and I know its weight.

I try another language, I invent rhetoric, I think perhaps this will be intimate of the rate of killing, this will sustain, will wait out; but I know better

this is the region called surmounting

this is the volcano called evidence

we are remainders of burning oxygen

we are just the end of helium, we are speeding

we are slow, water doesn’t end

Dionne Brand is a poet, novelist and essayist. Her latest books are The Blue Clerk (poetry), Theory (a novel) and An Autobiography of the Autobiography of Reading (essay).

References

Aimé Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism, trans. Joan Pinkham (2000)

Charles W. Chesnutt, The Marrow of Tradition (1901/2002)

Malick W. Ghachem, The Old Regime and the Haitian Revolution (2012)

Saidiya Hartman, ‘The End of White Supremacy, An American Romance’ (2020) Bomb 152

Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (2019)

Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (1995)

Anique Jordan, Fish Market (from the Salt series, 2015). Chromogenic print. 22 x 30 in. Courtesy the artist.

Anique Jordan is a Scarborough born lens-based and performance artist and curator.

Anique Jordan, Fish Market (from the Salt series, 2015). Chromogenic print. 22 x 30 in. Courtesy the artist.

Anique Jordan is a Scarborough born lens-based and performance artist and curator.