In the summer of 1990, a wall text accompanying an Emily Carr exhibition at the National Gallery declared that Carr “forged a deep bond with the native heritage” of British Columbia, and developed a “profound understanding of the meaning of that heritage.” That’s not a new notion: it’s a point often made about Carr by those who write earnest schoolbooks, and anyone who has read even a little about Canadian art will be familiar with it. But what does it mean? The answer involves a controversy that has been gathering around Carr in recent years, nibbling at the pedestal on which she has stood for two generations, drawing her into the midst of racial politics and postmodern theory, and challenging her place of high honour in Canadian art and women’s history.

How profound, exactly, was the understanding to which the wall pays tribute? Did Emily Carr understand native culture in the way she understood, say, the British-colonial Victoria in which she grew up? Or did she understand it in the way a diligent scholar may come to know a single foreign culture after years of study? Could she have explained the subtleties of belief by which coastal natives lived their lives and made their art? Or could she have described the differences between the Haida she encountered at Skidegate and the Tsimshian she met on the Skeena River in a way that either the Haida or the Tsimshian would recognize? Or does the word “profound,” which springs so easily to our lips, mean something vaguer in this case, something like a mystical leap of imagination and empathy by which Carr miraculously found her way, through otherwise impenetrable forests of exotic belief and custom, into the heart of a very native life?

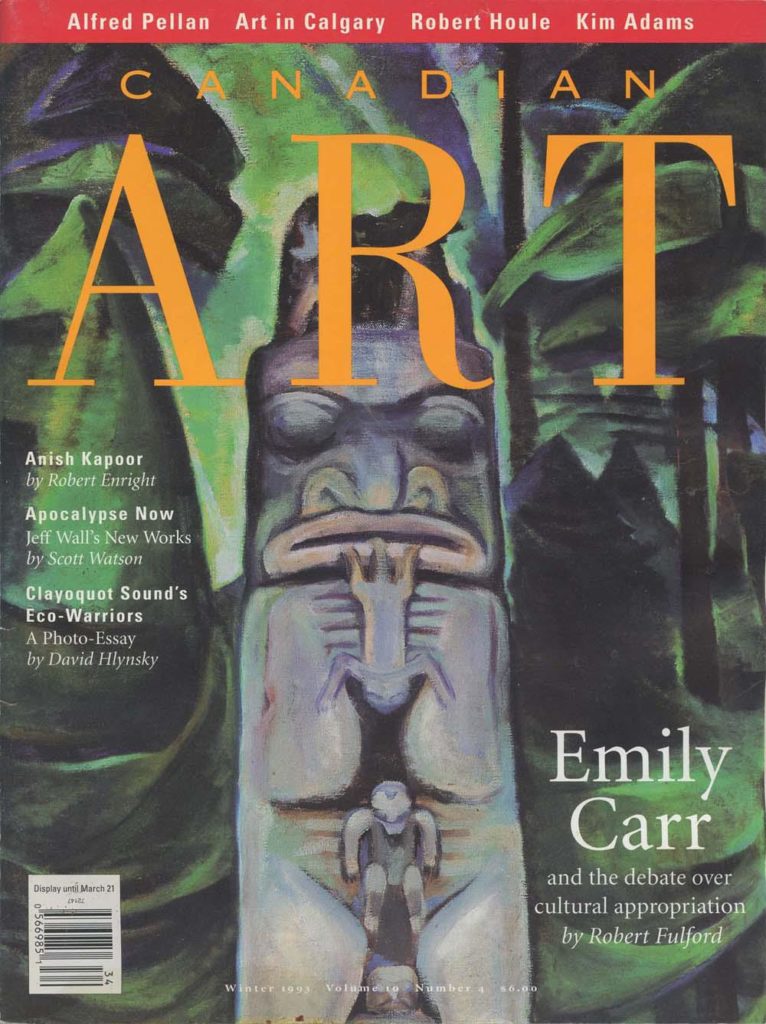

So begins our Winter 1993 cover story. To keep reading, view a PDF of the entire article.