“It’s not that I have an ethical problem with lying,” writes bartm, an anonymous member of the Masters Pick Up Artist Forum, in a post from March 2016. “It’s just that I don’t think I can get away with it.”

Pick-up artists (PUAs) are men—overwhelmingly straight and cis—whose “art” is picking up women. Stridently individualist, thoroughly capitalist and only nominally artistic, this is wellness for the toxic-masculinity set. It’s self-help that’s all, and only, about objectifying others.

bartm’s post could barely discuss selves without the jangling armour of scare quotes. He wrote of “the ‘real’ you,” and “the ‘upgraded’ you”; he was confused and frustrated by the phrase “just be yourself.” As artists have been for eons, bartm was curious about the nuances of deception. Spiralling existentially, he wondered: “Where do you draw the line between being yourself and lying?”

His questions resonated with Toronto artist Jennifer Laiwint, who was in New York when she found the forum. She was working on a project called How to Relax that responded to a 1980s self-help manual—another artifact of self-improvement quackery. After hearing a radio interview that reminded her of a past romance with a guy who revealed he’d used PUA tips to woo her, she wandered, cautiously intrigued, into the “manosphere.” She spent months trawling message boards and researching PUA history, and eventually made an exhibition of her experience.

But before it was material for art, bartm’s candour was just endearing; Laiwint liked his sincerity in addressing insincerity. As the thread continued, bartm’s bleakness emerged. Sorely lacking in confidence, he described himself as “a boring guy who never travels.” He’d been advised to mention travel on his dating profile, but bartm was dubious he could pass as a traveller—or as anyone worthwhile. “The travel thing was just an example,” he clarified, further down the thread. “What I was trying to say is I have nothing interesting going on.”

Whether in spite or because of the acutely misogynistic setting, Laiwint felt a pull to help. Since women are exclusively objects to PUAs, Laiwint had to create an alter ego. Already DJing as J Lai, she tweaked that moniker to fit the forum, and became Jay Lay. In a personal journal Laiwint used to process her time as Jay, she recalled her youthful habit of dreaming up personas. “Out of all the talents I could possibly have,” she wrote, “this was the one I longed for the most, a talent for being someone else.”

Narratives about PUA success typically feature a nerdy guy who follows the rules up into the ranks of the players, but Jay’s backstory reversed that arc. He’d had natural game, but some event (Laiwint doesn’t know quite what) softened him into a sensitive guy, and bent him on proselytizing. Laiwint decided that Jay would take Drake as his model of masculinity—“not that Drake doesn’t have his own brand of misogyny,” she journaled. But “he talks about his feelings, he loves his mom.” Laiwint would often put on Drake albums to get into character.

In posts rife with reassurances of masculinity (“bro,” “dude,” “man”), Jay encouraged the forum guys to connect with themselves and consider what, besides sex, they valued in a date. Laiwint balanced the advice she felt PUAs needed with the advice they’d hear. This wasn’t the careful counsel Laiwint—a confidante to friends since childhood—usually gave, but the crudeness of the forum came easily to her. She found it freeing to speak with such directness and aggression.

Freedom can be terrifying, though, and Laiwint sometimes regretted Jay’s flippancy: the casual way he used the word “depressed,” or the impatient Nikeism he’d use to goad bartm into changing his depressive habits. “Just change it. No excuses.” “No wonder you’re not getting pussy,” Jay chided in the midst of a feminist intervention. Laiwint asked her journal: “Am I undermining women?”

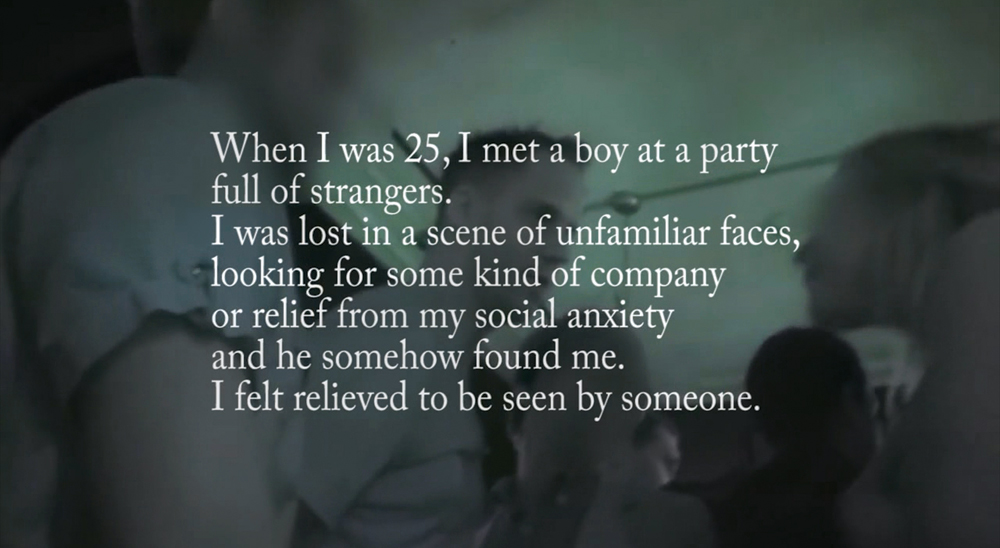

Jennifer Laiwint, In Field (work-in-progress), 2017. Video, 10 minutes.

Jennifer Laiwint, In Field (work-in-progress), 2017. Video, 10 minutes.

Laiwint also worried about the responsibility she bore to the men she engaged. At some point she and bartm began corresponding via private message, where he would confide “things he would never say on the forum.” Laiwint started to feel beyond her depths, both underprepared and overinvested. She would thrill when she sensed Jay’s influence on bartm, but bartm was disclosing content so intense Laiwint sometimes had to step away. She questioned the ethics of her quasi-therapeutic ambitions.

Then again: why should she show the members of the forum more respect than they showed women? The question borders another that Laiwint’s work, and our polarized political climate, has foregrounded. How much attention should we pay, and with how much empathy should we treat, those who flagrantly inflict harm or promote dangerous ideologies? Can we justify expending our resources to heal bad actors?

And if healing is the right course, who should administer it? Whether Jay Lay, a nascent life coach, might help bartm is not obvious; whether an artist impersonating Jay could is even less clear. It’s murky territory Laiwint charts in order to reach someone who might not otherwise be reached.

Beneath Laiwint’s inquiry into who can help (and who can be helped) runs a parallel uncertainty about who can be an artist. Last century, pediatrician-therapist D.W. Winnicott equated creativity almost directly with what we now call wellness: healing was a process of restoring creativity. Winnicott warned against defining creativity too narrowly, seeing it in much more than objects of art and craft. That’s no longer a radical claim, but Winnicott also insisted that creativity was not just the purview of the artist; “it belongs to being alive.” Creativity encompassed demeanours, comportments, “the approach of the individual to external reality.”

PUAs call the start of a seduction “the approach,” but how creative is their process? Winnicott wrote extensively about “play” in creativity, but the game PUAs learn is too rule-based to fit his definition. Pure play, according to Winnicott, is radically formless, and, crucially, a “non-purposive state.”

There’s a parallel here with Kant’s conditions for aesthetic judgment, and fodder for arguments about “art for art’s sake.” Though detractors argue it’s elitist to link art so definitively with leisure, Winnicott (among others) saw leisure not as an indulgence but as a developmental need.

Winnicott called societies that suppress creativity en masse “pathological communities.” That designation could describe much of contemporary Western culture, with its emphasis on products over process, results over experience, game over play. And if the culture at large positions the ends above the means, PUAs take those values, uncritically, to the extreme. Their purposes are overt and unwavering: the goal of “opening” (another word for approaching) is “closing” (PUA code for having sex, which is always the point). “They frame ‘being yourself’ as a strategy to get women,” Laiwint explains. “As a means to an end. It’s not for the purpose of self-growth, or just being comfortable with yourself. It’s for the purpose of seduction.”

When I met with Laiwint in August to discuss her project, she was still preparing for her exhibition, which opened in November at the Art Gallery of Mississauga in partnership with Toronto’s YTB Gallery. At the time, she didn’t know how she’d structure the show, or which correspondences to include. She’d followed her instincts into the work, and wasn’t sure what the project amounted to. She was busy questioning what everything she’d gathered had meant, deep in trying to understand the point of it all. She was in a place, familiar to many artists, where she might have welcomed the kind of clarity PUAs get from adhering to set rules and applying established formulas.

The artist’s comfort in play—that she did so much without knowing why—positions her diametrically against the others on the forum. Laiwint’s influence, though, may have softened the contrast slightly.

Months after his initial post, and still desperate for normative direction, bartm delighted Laiwint by seeming to forget the central premise of pick-up artistry. bartm had asked the forum something that anyone with a creative orientation to life might wonder: “What should my objective be in approaching?” A slew of interlocutors—Jay Lay included—responded, pretending to know.

Heather White is a writer and therapist in Toronto.

This post is adapted from a feature article in the Winter 2018 issue of Canadian Art themed on “Care and Wellness.” To get every issue of our magazine delivered to you before it hits newsstands, visit canadianart.ca/subscribe.

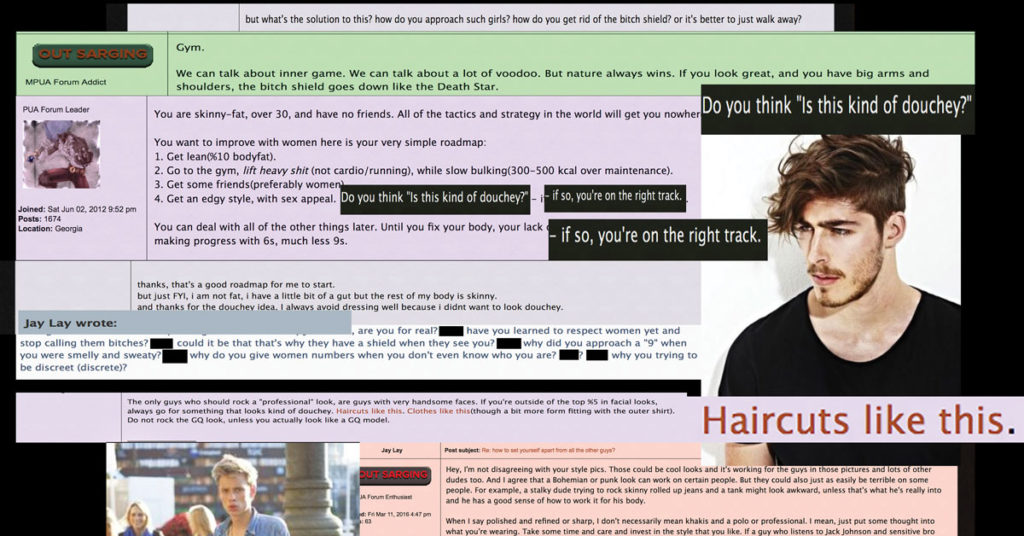

Jennifer Laiwint, Is This Kind of Douchey? (detail from work-in-progress), 2017. Digital collage.

Jennifer Laiwint, Is This Kind of Douchey? (detail from work-in-progress), 2017. Digital collage.