Between artworks and the museum—between the appearance of works on the art scene and their arrival at the institutions that will lastingly preserve them—there stands, in the majority of cases, the mechanism of the exhibition: a conceptually arranged and designed setting in which artworks are offered to the gazes of spectators and introduced into the discourse of art history. The works, first “invented” by artists and then “noticed” by art dealers, critics, collectors or curators, who recognize their unique character and underscore their import, are then finally “defined” by museums, which endow them with exceptional status.

Nowadays, this apparently logical sequence of events is often disturbed, clouded, its stages permutated or telescoped. This happens, for example, when a museum takes the initiative of commissioning an artwork or when an exhibition curator opts for a “worksite” exhibition format that provides the artist a context in which to bring a work into existence. Moreover, the sequence can be completed in a very short lapse of time, out of phase with the works’ production, and hence also out of phase with what is called the public “reception” of art.

In recent years, I have taken every opportunity to express myself on the role of the curator and on curation as a professional discipline. Like many of my colleagues, I feel a certain uneasiness in the face of an amateur curator who purports to spread the gospel of Art whereas the result is a simple entertainment put together by a celebrity who claims to be “so very touched” by art. Without being entirely against this, I find that most often curators with academic credentials and a propensity toward thinking, writing and the task of “reconnaissance” are the ones who ensure the requisite dovetailing of artwork and museum for society’s benefit. Without wishing to deny the intuition of art dealers, critics and collectors, or its validity, I feel that curatorial activity in Canada must contribute to mapping the art scene by organizing monographic exhibitions of emerging and recognized artists and thematic exhibitions engaging the issues that motivate creation today.

In the variety of exhibition types, one that presents a particular challenge is the survey exhibition. My desire to take up that challenge is what, more than two years ago, set in motion a huge project at the Galerie de l’UQAM entitled “Le Projet Peinture/The Painting Project,” which aims to draw up a balance sheet of current painting in Canada. Whenever I am asked to explain what lies behind this initiative, I point to three main considerations: the medium itself, since the exhibition examines various questions raised in Jean-François Lyotard’s Que peindre? (1987), in particular those on painting as an essence and a presence; second, the discipline of painting as an element in the history of Canadian art, which is eternally striving to take form; and third, the public, for whom painting seems to be the first thing that comes to mind when the visual arts are mentioned.

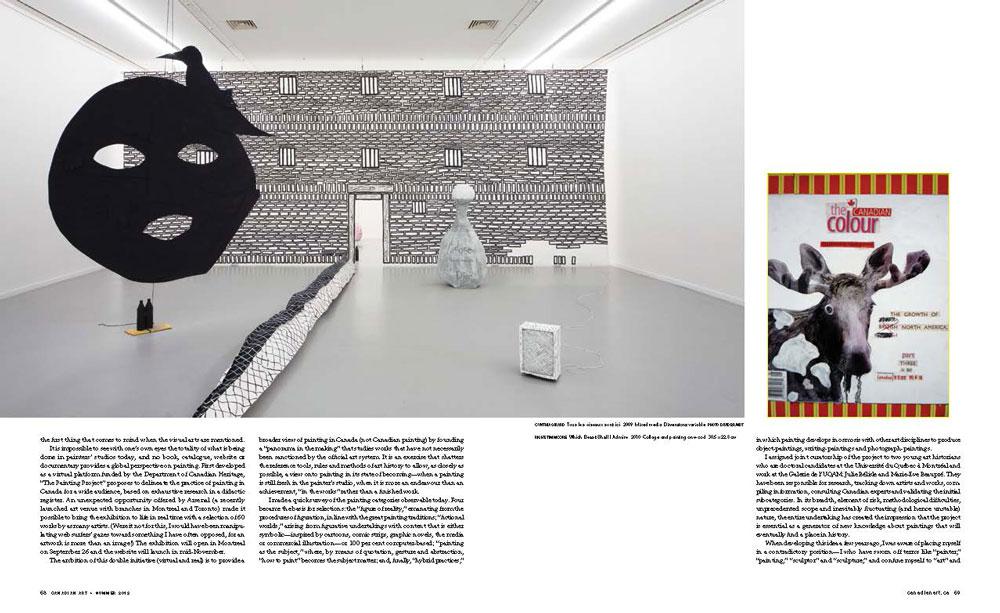

It is impossible to see with one’s own eyes the totality of what is being done in painters’ studios today, and no book, catalogue, website or documentary provides a global perspective on painting. First developed as a virtual platform funded by the Department of Canadian Heritage, “The Painting Project” proposes to delineate the practice of painting in Canada for a wide audience, based on exhaustive research in a didactic register. An unexpected opportunity offered by Arsenal (a recently launched art venue with branches in Montreal and Toronto) made it possible to bring the exhibition to life in real time with a selection of 60 works by as many artists. (Were it not for this, I would have been manipulating web surfers’ gazes toward something I have often opposed, for an artwork is more than an image!) The exhibition will open in Montreal on September 26 and the website will launch in mid-November.

The ambition of this double initiative (virtual and real) is to provide a broader view of painting in Canada (not Canadian painting) by founding a “panorama in the making” that studies works that have not necessarily been sanctioned by the official art system. It is an exercise that shatters the reference tools, rules and methods of art history to allow, as closely as possible, a view onto painting in its state of becoming—when a painting is still fresh in the painter’s studio, when it is more an endeavour than an achievement, “in the works” rather than a finished work.

I made a quick survey of the painting categories observable today. Four became the basis for selections: the “figure of reality,” emanating from the procedures of figuration, in line with the great painting traditions; “fictional worlds,” arising from figurative undertakings with content that is either symbolic—inspired by cartoons, comic strips, graphic novels, the media or commercial illustration—or 100 per cent computer-based; “painting as the subject,” where, by means of quotation, gesture and abstraction, “how to paint” becomes the subject matter; and, finally, “hybrid practices,” in which painting develops in osmosis with other art disciplines to produce object-paintings, writing-paintings and photograph-paintings.

I assigned joint curatorship of the project to two young art historians who are doctoral candidates at the Université du Québec à Montréal and work at the Galerie de l’UQAM: Julie Bélisle and Marie-Eve Beaupré. They have been responsible for research, tracking down artists and works, compiling information, consulting Canadian experts and validating the initial subcategories. In its breadth, element of risk, methodological difficulties, unprecedented scope and inevitably fluctuating (and hence unstable) nature, the entire undertaking has created the impression that the project is essential as a generator of new knowledge about paintings that will eventually find a place in history.

When developing this idea a few years ago, I was aware of placing myself in a contradictory position—I who have sworn off terms like “painter,” “painting,” “sculptor” and “sculpture,” and confine myself to “art” and “artist.” I duly noted the fact that research institutions (art museums and universities) are no longer much interested in the need for “sites” of this kind, and that the relevance of discipline-based overviews is questionable. And I admit that without the prospect of funds for placing art content on the web, I would never have embarked on the adventure—for how would one raise the money needed for such an undertaking? Where could one ever find the resources? Why would a university gallery of modest means expend its energy on it? I should emphasize that, as part of an institution of higher learning, a university gallery like the Galerie de l’UQAM recognizes its duty to disseminate art. Art is both a means of expression and a realm of knowing, and to aspire to establish such a perspective, one must thoroughly investigate the present while remaining conscious that it eludes us at every instant and while looking into all of memory’s blind spots.

I should also emphasize that in Canada, we do not aim to associate art with issues of identity, despite our awareness that collective sensibilities and memories are ascribable to artworks—to their aesthetic individuality and their exemplary value for society, politics and culture. Even the most current art cannot escape this realization. In Canada (and other places, no doubt), there seems to be a persistent gap that prevents us from reconciling the present with the past, the inventiveness and daring of our contemporary society with the historical loam from which we have emerged, the art of today with that of yesterday, and the painting that is being done now in a multitude of artist studios with that done by previous generations.

Average Canadians know practically nothing of their “national” art (a lack of awareness that is particularly remarkable in politicians, who are always eager for symbols). The greatest paintings by the Group of Seven and Quebec’s Automatistes—to mention but two past examples—seem to participate only superficially in a shared and valued collective artistic imagery. Does this explain the widespread feeling that an understanding of the work involved in creating today’s art does not reach citizens, politicians, decisionmakers— or our colleagues across the country and around the world?

Despite the paradox of a rich art scene evolving in the near silence of a society scarcely conscious of art, “The Painting Project” seeks to maintain an equilibrium. The exhibition investigates the liveliness of the Canadian painting scene. It includes major artists (but not all of them) and littleknown artists (though there could have been others). It demonstrates that to study the painting produced in Canada is to allow a reflection of us to emerge, one that contributes to the forging of an identity.

This is a feature article from the Summer 2012 issue of Canadian Art.