Based in London, England, Janice Kerbel is taking conceptual art into new and more personal realms of dematerialization

Riding the Tube from the farthest reaches of London’s East End—a little-known and deservedly so suburb called Barking—I discreetly study the tiny pamphlet in my hand. A complex arrangement of lines, an assortment of dots and a list of odd names are my only guide to my destination. I must navigate, tracing one vector as it links to another, making correspondences between the drastically reduced version of reality on the piece of paper and the chaotic world of subway cars, escalators, narrow tunnels and electronic time countdowns. It’s incredible that it can be contained in so simple a map, but transforming realworld disorder into a tiny diagram is an art unto itself, one that hides much more than it reveals.

I’m trying to find the expat Canadian artist Janice Kerbel’s London studio. She has given explicit instructions, but the vagaries of the sprawling city’s traffic (“give yourself an hour’s leeway,” advised my hosts) and my typically nervous travelling habits have left me clutching the Tube map like a talisman. Kerbel understands the power of maps. They provide secret knowledge, help us find our way, help us figure out where we are. Home Fittings, her ongoing series of site-specific drawings, identifies places in particular rooms where one can stand so as not to throw a shadow, or paths one can take without making a sound. These instructions help one find something (a location) and then lose something (oneself ).

When I finally find her—down an alley, past the Cubitt exhibition space and through a maze of studios—we sit down to talk about her work. This disparate oeuvre—it includes prints, HTML projects, installations, sound works and interdisciplinary collaborations—is united by Kerbel’s knack for hiding masses of research material in exactingly edited and extremely refined forms. She uses diagrams, instructions and simple images to make inscrutable puzzles that require almost forensic investigation.

“With Home Fittings,” she says, “I liked the idea that there was clearly this code when you looked at the works. The markings signalled this code but you weren’t really sure what the code was. I wanted them to be as discreet as possible.”

Her desire for discretion is evidence of a monkish obsession with reduction, condensation and simplification. Like a map-maker, she tries to contain as much information in as few markings as possible, while always ensuring that the map still functions. However, the artist in Kerbel prefers to keep the map teetering on the edge of collapse or uncertainty. The drawings in Home Fittings beg to be tested, but for most people the room is inaccessible. Creating such an untenable proposal, says Kerbel, “led me to think about making work that is somehow transitional. Work that suggests a particular state, but a state you can’t get to. The plan can be thought of as something that exists in its own reality, instead of the next stage. I wanted to make that next stage impossible or implausible: somehow you can’t get there, and that leaves the plan as something in its own right. But it holds on to that tension of the next stage.”

After studying cultural anthropology at the University of Western Ontario and fine art at the University of British Columbia and Emily Carr, Kerbel moved to London, England, in 1995 to do her MFA at Goldsmiths. The methods of the YBA art of the time were very different from hers and so, following graduation, instead of bursting onto the art scene in its attention-seeking way, she went undercover.

Like most new graduates, Kerbel was broke, yet intent on finding ways to raise money without sacrificing her practice. In her typically ambitious yet understated way, she focused her energy on a project that would end up being called Bank Job. She was planning a robbery.

“For a number of years I’ve been thinking about strategies of deception and how it relates to art,” she tells me. After almost two years of research, Kerbel completed the Bank Job installation and a bookwork titled 15 Lombard St. Both provided instructions for pulling off a foolproof heist at one of London’s high-end banks.

Folding interpretation into investigation, she invited the viewer/reader to consider the consequences of realizing her proposal. “With the bank robbery, it’s totally plausible and factual. There’s no fiction in it at all. However, you’re probably going to get caught: even if you make the perfect bank robbery on paper, you can’t plan for the accidents, you can’t plan for the guy who gets in the way and screws up everything.”

In 1999, Kerbel was invited by the digital-arts organization e-2 to create a HTML project. Once again imagining what she didn’t have—this time a vacation in the sun— Kerbel started with a location—map coordinates in the Bahamas—and hypothesized an idyllic island untouched by human hands. She worked within the limits of biology and environmental science, trying to make it as real as possible. She went so far as to imagine an indigenous bird and produce a recording of its calls. And then she put the island up for sale on the Web.

“The thing I wanted to do with this project was to imagine this paradise,” she says. “There, obsolescence is really built in, because if we were to go there, the fantasy isn’t sustainable.” Bird Island (www.bird-island.com) upped the ante in Kerbel’s ongoing series of untenable proposals by equating execution with death. Even if the island existed, its inevitable conclusion, once sold as resort property, would be ruination. Kerbel’s entire project, her Eden, was an invitation to that end.

On a smaller scale, closer to home and therefore more tempting, Kerbel began to design Home Climate Gardens. Each of these drawings is a garden plan customized for a particular indoor architectural environment. These schematic drawings—from wall-mounted gardens for a council flat to a respiration garden for a gym—provide a blueprint for ambitious gardeners to assemble the ideal plants in the best arrangement for unconventional sites. “I spent lots of time making sure the gardens were possible,” says Kerbel. “The choice of plants was dictated by light, humidity and the conditions in each room. But the fact is that plants really don’t want to be inside. So while they have this promise of producing these beautiful, lush gardens—the plan tells us this—in reality, it may be nothing like that.” On paper, the gardens are forever, but in reality, they would only bloom temporarily and, even with the resources of a good gardener, be doomed by hostile environments.

Kerbel’s research into plant life—particularly nocturnal flowers—led to one of her present projects: an Artangel commission to consider landscape and insomnia. Since many gardens in London are public parks where people can gather during the day but are locked out at night, Kerbel began to consider the idea of a community of insomniacs, an invisible community lying alone in their beds. She learned that it is common among insomniacs to leave a radio playing all night, either as distraction or for company, and wrote a short radio play for them. Structured, she hopes, like a lullaby, with a cast inspired by an assortment of night bloomers, the play will be slightly longer than the average time it takes for someone to fall asleep.

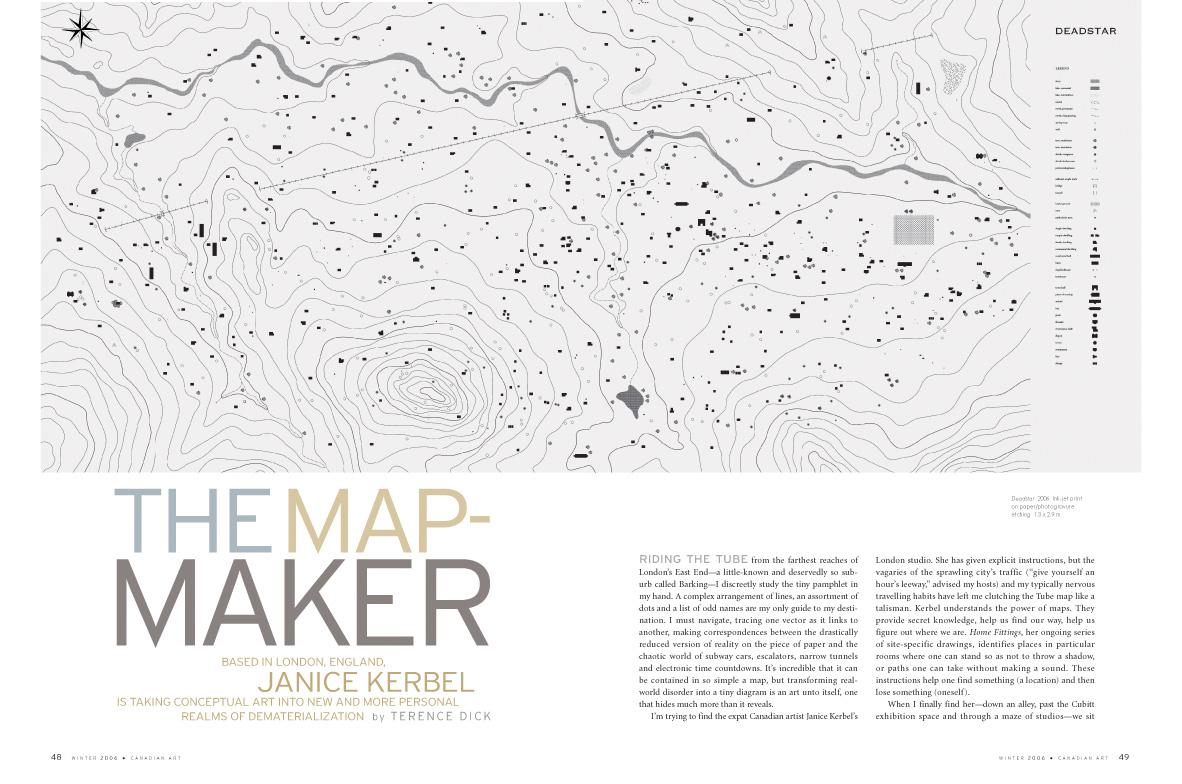

Kerbel’s other current project began with an interest in another creature of the night and led her across the ocean to a residency at the Ucross Foundation in Wyoming, where she could conduct some hands-on research in the desert. “I wanted to plan a ghost town,” she says. “One that would inevitably die, but would work from the perspective of ghosts. I wanted to make a town for ghosts, basically.” The town is called Deadstar and at the time of my visit she is finalizing the details of her topographic map. She explains the landscape to me, why she left the town in shadow, how she didn’t bother with roads because ghosts don’t need them. Deadstar’s buildings are scattered all over the valley and Kerbel is nice enough to tip me off that they’re arranged according to the star map. Given that the lights we see in the night sky have travelled so far and for so long and that their original sources might have sputtered out thousands of years ago, conflating stars and ghosts makes sense.

As we look at the drawing, Kerbel contemplates how this most recent obsession fits in with her previous work: “Almost every project I’ve done has an element of invisibility. There’s something held back that you can’t actually see. And I was thinking about ghosts as this other manifestation of the invisible, where you didn’t actually know; you thought it was true but you didn’t know.” For someone who spends so much time gathering information and displaying her findings, Kerbel seems awfully interested in uncertainty. And even more than an epistemological failing, the absences in her work—the things that are hidden in her speculative plans—allude to a greater loss. From losing oneself to a lost paradise to losing sleep to lost souls, she hints at our inevitable mortality. If the population of Deadstar is any indication, perhaps her work is better suited to the afterlife.

It’s time to go. After advising me on how best to get through the maze that is central London, Kerbel says goodbye and I head out through the alley, slightly anxious about the consequences of following her instructions. Consulting the Tube map once again, I am reminded of the inscrutable void that lies behind the stark surfaces of her art and the care with which she leads people to the edge.

Opening spread for "The Map-Maker" from our Winter 2006 issue.

Opening spread for "The Map-Maker" from our Winter 2006 issue.