My name is Jenny Irene Miller. My Inupiaq name is Wiagañmiu. My family on my mother’s side originates from the Native Village of Kiŋigin, or as it is known more commonly, Wales, Alaska. I come from the Inupiat people of the Bering Strait region of Alaska. I’m a photographer. I identify as queer. I also identify as Inupiaq, white, gay and Two-Spirit. I’m originally from Nome, Alaska. For the past five years, I have been living my truth and expressing my queer identity through art and storytelling. I do this by being open about my identity and sexuality, sharing my story and exploring my identities through photography, video and sound art. I am an activist and my work supports the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and Indigenous LGBTQ+ and Two-Spirit communities. Currently, my urgent purpose is to find and claim space for Indigenous LGBTQ2+ people to thrive in our contemporary reality.

Before I began this work, mainstream society, pop culture and Christianity had shaped my self-image. Some influences were positive. Some were toxic. Early on in life, I was taught colonial ideals, communicated by those around me through the teachings of the Bible. Learning the idea that loving someone of the same sex or gender was wrong caused me to feel shame for being the person I was growing into. The pressures from family and community members—who believed that their Christian views trumped mine, that LGBTQ2+ people were misguided, that they were choosing to live a life of sin and that we could simply be changed through conversion therapy—discouraged me from expressing my queer identity. I found myself in heterosexual relationships. Relationships that did not feel right or true. I was only hurting myself by not being true to myself.

Jenny Irene Miller, Ricky Tagaban, 2016. “My name is Ricky Tagaban. I’m L’uknax.adi from Diginaa Hit, and Wooshkeetaan wadi from Xeitl Hit. My dad is Tlingipino and my mom is German and Italian.”

Jenny Irene Miller, Ricky Tagaban, 2016. “My name is Ricky Tagaban. I’m L’uknax.adi from Diginaa Hit, and Wooshkeetaan wadi from Xeitl Hit. My dad is Tlingipino and my mom is German and Italian.”

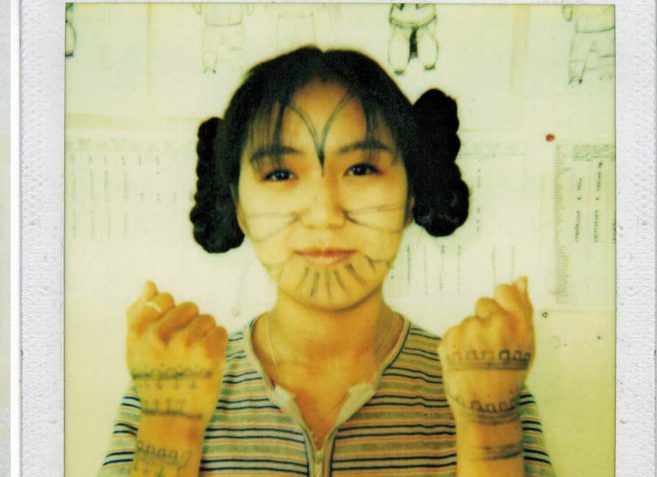

Jenny Irene Miller, Tuiġana, 2016. “Atiġa Tuiġana, Ulġuniqmiuŋuruŋa. I am Inupiaq. My namesake is Tuiġana. My family is from Wainwright, Alaska, which is about 90 miles southwest, down the coast from Utqiaġvik. My aapaaluk is the late Billy Blair Patkotak Sr. and my aakaaluk is Amy Patkotak (Bodfish).”

Jenny Irene Miller, Tuiġana, 2016. “Atiġa Tuiġana, Ulġuniqmiuŋuruŋa. I am Inupiaq. My namesake is Tuiġana. My family is from Wainwright, Alaska, which is about 90 miles southwest, down the coast from Utqiaġvik. My aapaaluk is the late Billy Blair Patkotak Sr. and my aakaaluk is Amy Patkotak (Bodfish).”

Jenny Irene Miller, Bethany Horton, 2016. “My name is Bethany Horton. I was born and raised in Nome, Alaska. I am Alaska Native and belong to the Nome Eskimo Community. My mother was born in Clover, New Mexico, and she is white—British and Welsh. My father was born in Greenville, South Carolina, and he is Alaska Native and white.”

Jenny Irene Miller, Bethany Horton, 2016. “My name is Bethany Horton. I was born and raised in Nome, Alaska. I am Alaska Native and belong to the Nome Eskimo Community. My mother was born in Clover, New Mexico, and she is white—British and Welsh. My father was born in Greenville, South Carolina, and he is Alaska Native and white.”

Jenny Irene Miller, Andrew Jake Miller, 2016. “My name is Andrew Miller. My Inupiaq name is Senungetuk, after my great-grandpa, which later became our family’s surname following the 1918 influenza epidemic that hit Wales, Alaska, and the arrival of missionaries. I am originally from Nome, Alaska.”

Jenny Irene Miller, Andrew Jake Miller, 2016. “My name is Andrew Miller. My Inupiaq name is Senungetuk, after my great-grandpa, which later became our family’s surname following the 1918 influenza epidemic that hit Wales, Alaska, and the arrival of missionaries. I am originally from Nome, Alaska.”