Production still from Nyla Innuksuk’s feature film Slash/Back (2020).

Production still from Nyla Innuksuk’s feature film Slash/Back (2020).

Nyla Innuksuk

Virtual reality (VR) is a new medium increasingly embraced by contemporary artists. Some Indigenous artists are using it to envision an alternate world, while others use it to bring people closer to places and communities that previously could not be easily reached. One such VR artist is Igloolik-born Nyla Innuksuk, who is an accomplished filmmaker, writer and producer as well as the CEO of the Toronto company Mixtape VR. Her work explores the storytelling capabilities of new technologies and where this can fit in with filmmaking. Through VR, Innuksuk continues to stress the importance of engaging with Inuit communities and bridging the gaps between Inuit Nunangat and the South. Access to VR technology in northern communities is limited, and it is thanks to the help of people like Innuksuk that many Inuit and other Indigenous youth have had the opportunity to play with and be inspired by virtual worlds. In addition to her work with VR, Innuksuk also consulted on the creation of the newest Marvel character, Amka Aliyak—a.k.a Snowguard—who comes from Pangnirtung, Nunavut.

Margaret Nazon, Milky Way Galaxy, 2009. Beadwork on canvas-backed black velvet, caribou bone and beads. Courtesy the artist.

Margaret Nazon, Milky Way Galaxy, 2009. Beadwork on canvas-backed black velvet, caribou bone and beads. Courtesy the artist.

Margaret Nazon

Based in Tsiigehtchic, Northwest Territories, Gwich’yaa Gwichin artist Margaret Nazon has been sewing since she was a young girl, learning various techniques from her mother and from her time attending residential school. She works primarily with fabrics and beading to explore and express herself. In 2009, she became inspired by many of the stunning photographs being released by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and in response began a series of wall hangings featuring beaded galaxies, planets and supernovas. Her materials and subject matter combine the traditional mediums of beading and embroidery with “otherwordly” imagery, linking the cosmos to the terrestrial. In Milky Way Galaxy (2009), Nazon included a piece of caribou bone to represent a celestial centre and give depth and texture to the work. Such depictions of faraway planets and stars—seemingly surreal and inaccessible—thus become tangible through the colourful layering and cultural grounding of Nazon’s beadwork.

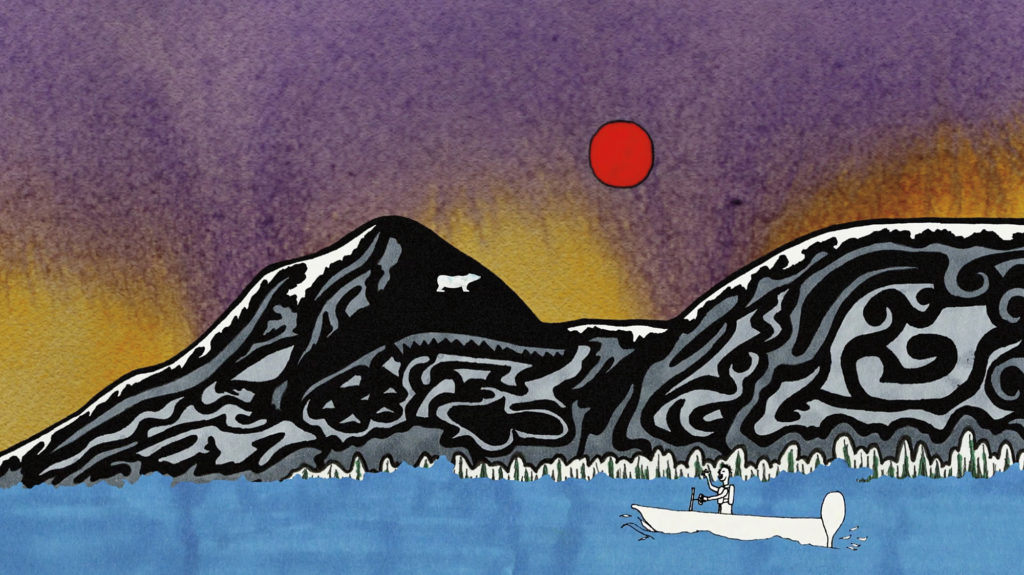

Echo Henoche, Shaman (still), 2017. Hand-drawn animation, 5 min. Courtesy the artist/the National Film Board of Canada.

Echo Henoche, Shaman (still), 2017. Hand-drawn animation, 5 min. Courtesy the artist/the National Film Board of Canada.

Echo Henoche

Hailing from Nunatsiavut, Echo Henoche is part of a growing community of artists and professionals who are promoting Inuit identities in the context of contemporary art practices and cultural expression. Her short film Shaman (2017), produced in collaboration with the National Film Board, has reached audiences around the globe. Traditionally, Inuit stories were told orally to family and children and passed down through generations. By using drawings paired with modern animation techniques, Henoche was able to retell her favourite story of a shaman who turns a polar bear into stone—a story that her grandmother told to her when she was young. The lines of her intimate ink drawings imaginatively trace the contours of both the Nunatsiavut landscape and the creatures that inhabit it. The sparse soundscape, consisting only of drumming and sound effects, places an emphasis on the story’s drama. Henoche’s visual style can seem unassuming, yet it is exactly this simplicity and directness in her work that connects her to many people, across Inuit Nunangat and beyond, who practice drawing as a means of personal and cultural expression.

Kakiorneq by Paninnguaq Lind Jensen. 2018. Courtesy the artist.

Kakiorneq by Paninnguaq Lind Jensen. 2018. Courtesy the artist.

Paninnguaq Lind Jensen

Greenlandic tattoo artist Paninnguaq Lind Jensen uses a form of traditional tattooing to affirm her identity and to celebrate her values. Her story has influenced people in Canada and internationally, and her work is carried forth on the bodies of the people upon whom she traces these lines of history. Interest in the traditions of Inuit tattooing, and their revitalization, has grown in recent years. The once-banned art form has resurfaced, and with it, a dedicated number of artists willing to learn the techniques through stories heard and passed down from Elders and generations past. In an online video blog, she explains how helping to revitalize the practice of tattooing is a way for her to reconnect with her own personal happiness and sense of identity. She has been an apprentice of fellow Greenland Inuit tattoo artist Maya Sialuk Jacobsen, and it is from Jacobsen that she has learned the traditional tattooing techniques—along with all of its complexities around health and safety concerns. Despite these concerns, both Paninnguaq and Jacobsen continue to educate many others about the cultural history of tattoos. It is important for artists to love what they do, and keeping our integrity as Inuit people can sometimes be challenging—Paninnguaq bridges that gap. As a young, emerging Inuk tattoo and visual artist, she continues to be an inspiration.

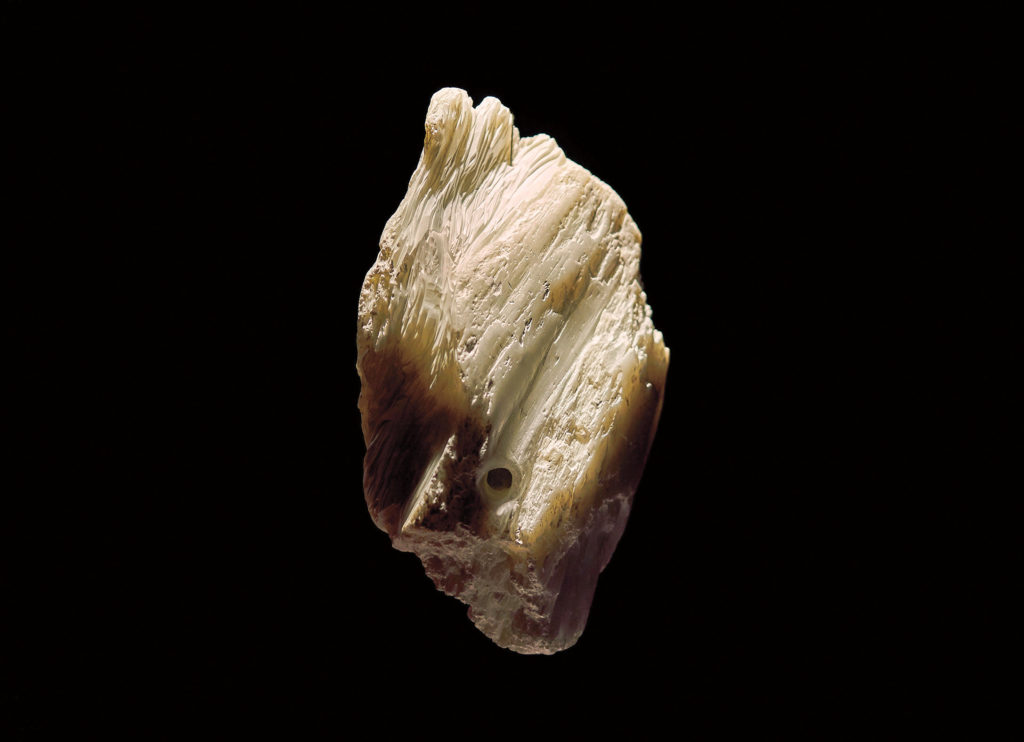

A detail from Niap’s ᑲᑕᔾᔭᐅᓯᕙᓪᓛᑦ Katajjausivallaat, le rythme bercé (2018). Courtesy Oboro. Photo: Romain Guilbault.

A detail from Niap’s ᑲᑕᔾᔭᐅᓯᕙᓪᓛᑦ Katajjausivallaat, le rythme bercé (2018). Courtesy Oboro. Photo: Romain Guilbault.

Niap

Originally from Kuujjuaq and now based in Montreal, where she attends Concordia University, Niap is striking her own path in the Inuit art world. There is a diversity in her practice, with rich imagery taken from the relationship she shares with the Arctic. Her respect for traditions, her sense of innovation, her attention to detail and respect for art is impressive, whether it be through drawing and painting, photography and carving, or drum dancing and throat singing. In ᑲᑕᔾᔭᐅᓯᕙᓪᓛᑦ Katajjausivallaat, le rythme bercé, presented at Oboro in Montreal, Niap suspended large stones in an installation that was accompanied by a throat-singing soundtrack. The sculptures were made from Brazilian soapstone (a material used by many Inuit carvers) and were meant to resemble the vocal anatomy, where the rhythms of throat singing begin. It is an example of the many ways Niap reaches out to her community in public, and engages us with Inuit culture in a respectful and innovative way. Niap brings Inuit traditions into a contemporary art context, and her increasing art-world recognition is a reflection of the success of this important dialogue.

Marc Fussing Rosbach, Akornatsinniittut - Tarratta Nunaanni (still), 2017. Film, 93 min. Courtesy the artist.

Marc Fussing Rosbach, Akornatsinniittut - Tarratta Nunaanni (still), 2017. Film, 93 min. Courtesy the artist.

Marc Fussing Rosbach

What is most impressive about Greenlandic filmmaker Marc Fussing Rosbach is not just his youthful age (he’s 23), but that he’s produced the first Greenlandic sci-fi/fantasy feature film, Akornatsinniittut – Tarratta Nunaanni (Among Us – In the Land of Our Shadows), released in 2017, as a self-taught filmmaker. He created the visual effects, composed the music, directed, edited and even co-starred in the film. Rosbach has been creating videos from the moment he started experimenting with filmmaking software and would watch YouTube tutorials on video editing or creating visual effects, all to give him the skill set to make Akornatsinniittut – Tarratta Nunaanni. For the first time, we see onscreen the traditional stories of powerful shamans—stories that have long been told by Elders—brought to life through the magic of cinema. The modern capabilities of video and visual effects help drive the believability of these traditional stories, while simultaneously creating an entertaining film. Recently, Rosbach has been busy filming the sequel to Akornatsinniittut – Tarratta Nunaanni, and is in the planning stages for a third film.

Jesse Tungilik, Bottled, 2018. Bronze-cast figure, clear polyester resin and bottle. Courtesy the artist.

Jesse Tungilik, Bottled, 2018. Bronze-cast figure, clear polyester resin and bottle. Courtesy the artist.

Jesse Tungilik

Iqaluit-based artist Jesse Tungilik has been steadfastly working within institutional frameworks to push forward the envelope of Inuit expression through the arts. While employed within these institutional channels (Tungilik was previously executive director of the Nunavut Arts and Crafts Association), he does not shy away from controversial topics in his artistic practice. Using sculpture, mixed media, jewellery and writing to express himself, Tungilik’s art is innately personal, and often speaks to the underlying problems within the socio-political realities and constructs of “the North.” In Manhole Hunter (2012), a solitary Inuk hunter, carved from caribou antler, crouches on a slab of asphalt with spear in hand, poised over a metal manhole, seemingly in wait for his meal. Although small and subtle in appearance, its message speaks loudly to the difficulties some Inuit face while living in urban environments: food insecurity, homelessness and a feeling of disconnect from community. Last summer, Tungilik participated in the TD North/South Artist exchange, travelling to the Banff Centre for a four-week residency where he was able to further expand on his sculpting skills, as well as try his hand at bronze casting and 3-D printing. This opportunity led him to develop new works, like Bottled (2018), which reflect on and address the intergenerational trauma faced by many Inuit.

Mary Kunuk, Unikausiq (Stories) (still), 1996. Computer animation, colour and sound, 4 min 54 sec. © Arnait Video Productions. Courtesy Vtape.

Mary Kunuk, Unikausiq (Stories) (still), 1996. Computer animation, colour and sound, 4 min 54 sec. © Arnait Video Productions. Courtesy Vtape.

Mary Kunuk

Igloolik is a community nestled on the Melville Peninsula just west of Baffin Island and north of Hudson Bay. That is where Igoolik Isuma Productions began, as well as a host of important related projects including Arnait Video Productions. Mary Kunuk, one of the founders of Arnait, has played a very important but underrated role in this development. How many others before her can claim to have produced a culturally sensitive video using some of the earliest digital images—on an Amiga computer? Why aren’t we talking about this more? The storytelling in her short computer-animated film Unikausiq (Stories) (1996) is a rich reflection of the intangible world of traditional Inuit cosmogony told from the perspective of an Igloolik woman. At the same time, it’s unpretentious, and very intimate. While Kunuk’s use of computer animation is innovative, the style she employs in her drawings, and the story she tells with them, remains anchored deep in local traditions. Each frame can be read as a reflection of the Inuit print styles from the Baffin regions. There is a subtlety here that could be missed if one does not know the particular lay of the land and pace of the Arctic, or take the time to look and listen.

Barry Pottle, Caplin Roll, Middle Cove, NL, 2018. Digital photograph.

Barry Pottle, Caplin Roll, Middle Cove, NL, 2018. Digital photograph.

Barry Pottle

Nunatsiavut photographer Barry Pottle garnered national attention with Awareness Series (2011), a series of photographs of disc numbers, the Eskimo Identification Tag system used by the Canadian government from the 1940s to 1970s as way of identifying Inuit for census purposes. Pottle is originally from Rigolet and now lives and works in Ottawa, and has been capturing different viewpoints for many years. His practice offers the opportunity to photograph the growing urban Inuit community—a community that, as an idea and concept, is still relatively new to him. His ongoing The Nasaq Series (2014–), like much of his work, is playful and evocative, with subtle, humorous juxtapositions of Inuit identity concepts. His extensive collection of photos includes many images that are visually and conceptually striking, including this one, which shows caplin washing ashore in Middle Cove, Newfoundland. At first glance it looks like some kind of fantastic or abstract painting, but the moment it captures is the result of a well-planned shot. The marvel of a species in a dance with nature, the composition and movement, and the wonder this photo evokes are a testament to Pottle’s strong eye and ability to explore different moods in order to find his niche.

Taqralik Partridge, Tusarsauvungaa (detail), 2018. Series of five elements with cotton, polyester, wool, silk, glass beads, metal beads, Canadian sealskin, reindeer leather, thermal emergency blanket, Pixee lures, plastic tarp, Canadian coins, tamarack tree cones, dental floss, artificial sinew, goose feather and river grass. Dimensions variable Photo: Paul Litherland / Studio Lux. Courtesy Leonard and Bina Ellen Art Gallery.

Taqralik Partridge, Tusarsauvungaa (detail), 2018. Series of five elements with cotton, polyester, wool, silk, glass beads, metal beads, Canadian sealskin, reindeer leather, thermal emergency blanket, Pixee lures, plastic tarp, Canadian coins, tamarack tree cones, dental floss, artificial sinew, goose feather and river grass. Dimensions variable Photo: Paul Litherland / Studio Lux. Courtesy Leonard and Bina Ellen Art Gallery.

Taqralik Partridge

Originally from Kuujjuaq, Nunavik, but now living in Norway, Taqralik Partridge is not only an accomplished artist and writer; like many Inuit, she is also a very talented sewist. Partridge is known for her poetry and spoken word performances, which bring us to the Arctic through storytelling as she weaves portraits of Inuit life with her words. That very same intimate sensibility, which shines forth publicly, is also visible in the textiles and beadwork she creates at home. Starting from objects with a functional purpose—a nasaq, a jacket, mitts—sewists learn to embellish their craft with unique variations and details. The stories Partridge tells carry that same attention to detail, and her beadwork and textiles tell a story too. The intricate beadwork pieces presented in the exhibition “ᐊᕙᑖᓂᑦ ᑕᒪᐃᓐᓂᑦ ᓄᓇᑐᐃᓐᓇᓂᑦ: Among All These Tundras” mix together several elements and found objects in addition to beads, including plastic tarp, scrap materials evocative of worn clothing, fish hooks with price tags still on and a single penny showing the face of the Queen. They draw attention to the issues faced by street-involved community members, especially in urban centres such as Montreal. The decision to also show the face of the Queen further reminds us of Canada’s colonial history, and the complicated relationship between Inuit and the Crown.