It was like I was afraid to come out of the closet as a full-blown Inuk. Born at a time when the Danification of Greenlandic Inuit was strong, I lived many years assimilated, though never in doubt of my ethnicity. As children we learned Danish in school rather than our own language. We were urged to travel to Denmark to study, to come back refined, more Danish and less Inuk. We were repeatedly told that there was no future in our language, our knowledge. I felt a disconnection from my reality and a deep sense of longing for my unreachable culture. Like many others I ended up in Denmark as a young teenager, later moving from country to country in Europe, living in a rootless state. Eventually I found a world that took me in without questioning my ethnicity. I became a tattooer. A Western commercial tattooer. It took me 10 years of tattooing and travelling in the Western world before I found my way back to my culture and my homelands. It was a tiny little mask that showed me the way to my roots.

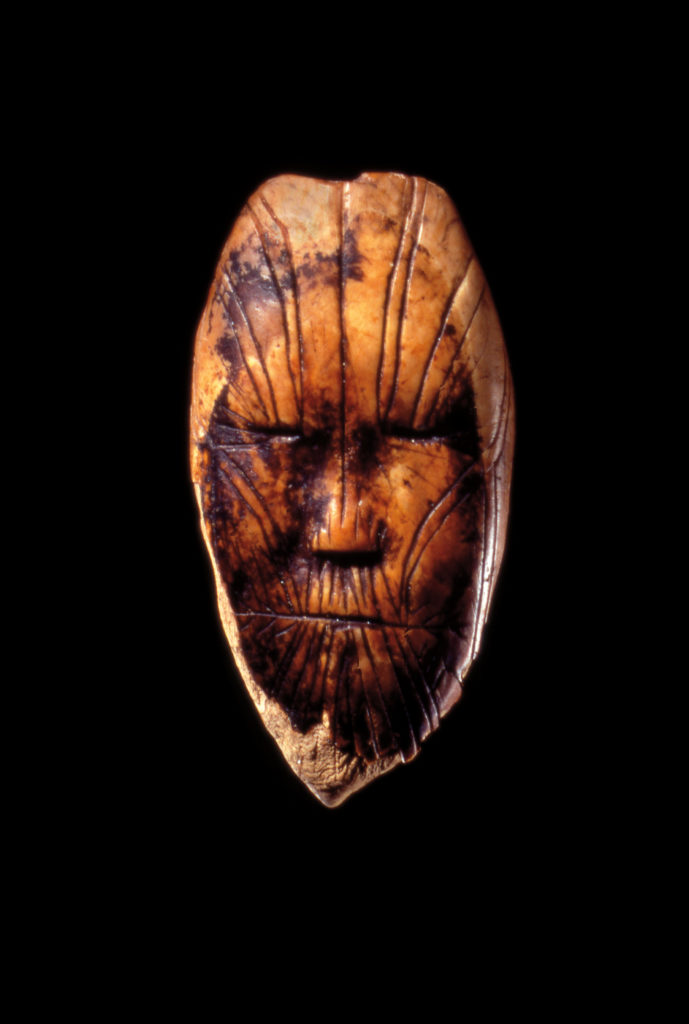

At first her little face seemed wrinkled. Then I discovered that the lines were intricate tattoo patterns. She is at least 3,600 years old and from the Dorset culture—the culture that inhabited some circumpolar regions before the Thule, the culture that I descend from! She pulled me in. I understood that my cultural pride could no longer be held back. Her beautifully curved cheek markings are almost exactly the same as the lines found on the 500-year-old Greenlandic mummies from Qilakitsoq. These lines have remained unchanged for millennia and through the long distances of Inuit migration. On both sides of her mouth she has beautiful little branch-like patterns. Her chin lines are exactly the same as the lines I tattoo on Inuit women today: precise straight lines from lip to chin that mark childhood’s end.

The collected oral traditions of Inuit have been passed down over generations, and are a way that angakkut inform Inuit on maintaining balance between the Visible World of the humans and the Invisible World of the spirits. Even in our colonized, Danified community, the stories were kept alive, like our ability to make clothing of skins. Alive, like our hunting knowledge. I was always reminded that we have a rich history and culture to be proud of. I was also constantly reminded to act Danish.

Maskette, Devon Island, Nunavut ca. 1900–1600 BC. Walrus ivory, 5.4 cm x 2.9 cm x 8 mm. Collection Canadian Museum of History.

Maskette, Devon Island, Nunavut ca. 1900–1600 BC. Walrus ivory, 5.4 cm x 2.9 cm x 8 mm. Collection Canadian Museum of History.

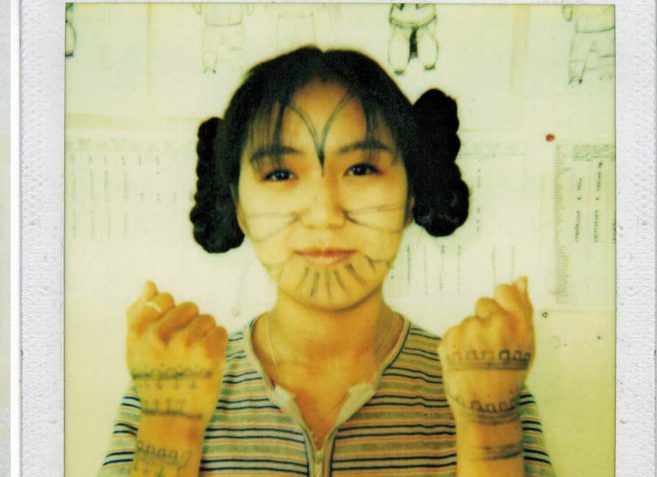

Sassuma Arnaa finger markings. Photo: Maya Sialuk Jacobsen.

Sassuma Arnaa finger markings. Photo: Maya Sialuk Jacobsen.

Maya Sialuk Jacobsen, Yupik qajaq frame parts, 2019. Watercolour, 30 x 21 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Maya Sialuk Jacobsen, Yupik qajaq frame parts, 2019. Watercolour, 30 x 21 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Maya Sialuk Jacobsen, Forehead markings, 2019. Watercolour, 30 x 21 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Maya Sialuk Jacobsen, Forehead markings, 2019. Watercolour, 30 x 21 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Skin-stitching a talloquteq. Photo: Per-Erik Dahlman.

Skin-stitching a talloquteq. Photo: Per-Erik Dahlman.