“No man is an island,” wrote John Donne.

“Beg to differ,” counters Suzanne Hill with “Singular,” her probing, unsentimental solo exhibition derived from five years of thinking and art-making on the idea of aloneness.

On view at the New Brunswick Museum until April 16, the show is a manifold meditation on the ultimate isolation of life and the paradoxical way we are alone together.

It’s ironic, then, how much creative company the show has generated, how much inspiration and new work it has prompted among other New Brunswick artists.

Rothesay writer Anne Compton, a Governor General’s Award–winning poet, has composed four poems around Hill’s interest in rituals and shadows, while Igor Dobrovolskiy, artistic director of Atlantic Ballet Theatre of Canada, a professional company based in Moncton that tours internationally, has created a dance—and discovered a new vocabulary of movement—in response to how Hill uses the body to express ideas.

“She’s a conceptual artist, as far as I’m concerned,” Compton says. “She’s driven by ideas.”

Compton has been in a long, sporadic conversation with Hill about the show. For five years or so, the two have met for lunch every couple of months for “ambulatory” chats about their work and their lives.

“There are things poets and artists have in common,” Compton says. “They’re both image-creators. Both are watchers. Both are interested in form.”

Atlantic Ballet Theatre of Canada performs Igor Dobrovolskiy’s Body’s Streams in Suzanne Hill’s exhibition “Singular” at the New Brunswick Museum. Photo: Courtesy of the New Brunswick Museum.

Atlantic Ballet Theatre of Canada performs Igor Dobrovolskiy’s Body’s Streams in Suzanne Hill’s exhibition “Singular” at the New Brunswick Museum. Photo: Courtesy of the New Brunswick Museum.

At the same time as Hill was working out what would become “Singular,” Compton was writing a long essay on ekphrastic poetry—poetry about paintings—that will be published in her forthcoming book, Afterwork: Essays on Literature and Beauty, this summer.

Compton’s conversations with Hill inspired the essays and informed the poems Compton wrote in response to “Singular”: the trio “Three Stories of Shadows (for Suzanne Hill)” and “Ritual for the Old Year.”

“Ekphrastic poetry is always the footnote to the painting,” Compton says. “The poem is always after.”

As Peter Larocque, the New Brunswick Museum curator who worked on “Singular,” said at the exhibition’s opening, “This is work that instigates other works.” As part of the event, the poet and dancers presented their pieces alongside the art that inspired it, performances they reprised at an evening event this winter.

“It’s a triple whammy,” Hill says recently from her studio in an old brick building that looks over the Saint John harbour. Then she jokes, as she often does: “It’s like punching them in the head and then giving them a kick in the shins.”

More seriously, though, there’s no denying that the poetic and dance elements offer new entry points into the artist’s ideas and process. No denying the quality of the poetry and dance, either—not surprising considering Hill, Dobrovolskiy and Compton have all received the Lieutenant-Governor’s Award for High Achievement in the Arts, one of New Brunswick’s top honours.

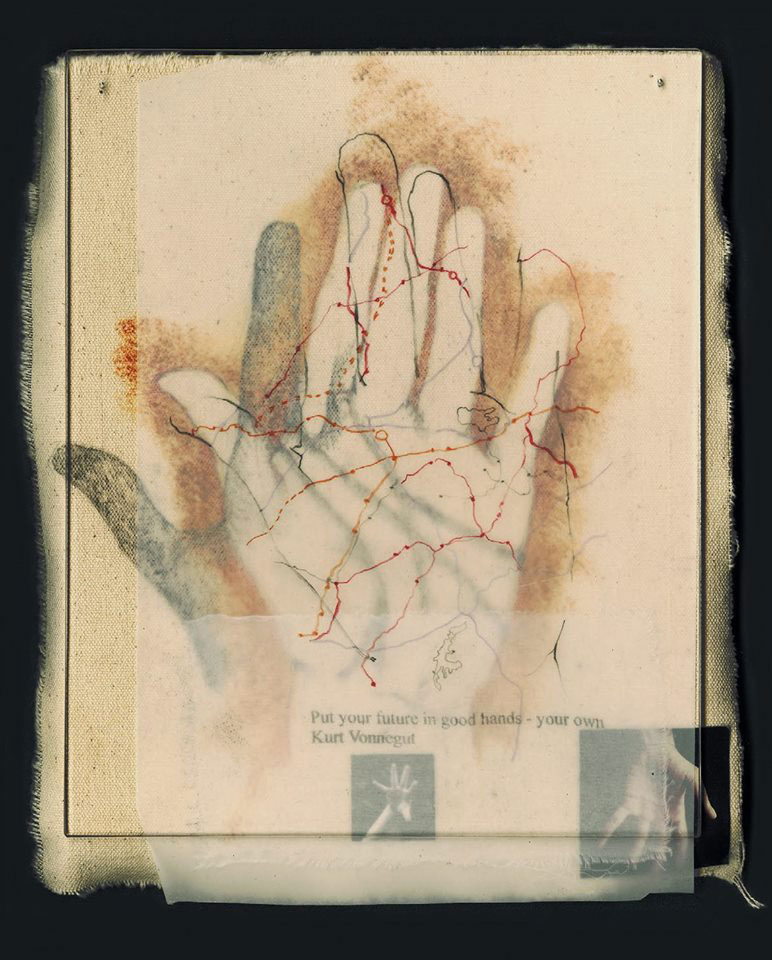

Suzanne Hill, Identity (detail), 2016. Courtesy of the New Brunswick Museum. Photo: Rob Roy Reproductions.

Suzanne Hill, Identity (detail), 2016. Courtesy of the New Brunswick Museum. Photo: Rob Roy Reproductions.

As interesting and flattering as these additional elements are, however, “Singular” doesn’t need them. They are gravy on Hill’s feast of a show, which, after the dancers have slipped out of the room and the poet’s voice fades, is as it was before they others arrived: whole, complex and powerful, utterly self-sufficient.

Hill has always gone it alone, really. Living far from the big hubs of contemporary art, she has forged, solo, a practice and vision that, while not really part of the national scene, has, over more than 30 years, been exhibited and collected nationally and internationally.

It’s possible, then, to view “Singular” not just as a comment on the human condition, but on the nature of creativity generally and Hill’s practice specifically. Almost every day, for hours a day, she works alone in her studio, where she arrives as early as 7 a.m., often the only person in the four-storey former factory building at that hour.

Her rigour and discipline of thought come through clearly in “Singular,” with the titles of its five discrete yet related installations hinting at some of her preoccupations: Towers/Solitude, Decisions, Shadow, Personal/Private Rituals and Identity. These are complemented by a suite of six of her trademark figurative works, which feature headless, androgynous, earth-toned beings engaged in ambiguous gestures.

Suzanne Hill, Body Language II, 2014–2015. Courtesy of the New Brunswick Museum. Photo: Rob Roy Reproductions.

Suzanne Hill, Body Language II, 2014–2015. Courtesy of the New Brunswick Museum. Photo: Rob Roy Reproductions.

“Singular” doesn’t just resonate with itself, but with Hill’s career, striking some very long chords in a series of paintings that harken back to her student days at Mount Allison, where she studied under Alex Colville.

“I wanted to provide I could still paint realist,” she says. She also asked herself, “’Have you still got the eye?’” (She does.)

The show’s size and its cohesion reveal an artist who isn’t afraid to wander, but knows how not to get lost in her ideas, each suite a breadcrumb trail leading into the forest of her thinking, a dense, somewhat dark and complex ecosystem where figures and shadows loom and idiosyncratic order is imposed according to personal need.

“There are patterns in the way the mind works that are individual to you,” Hill says. “Everybody has rituals. That’s what you do to keep control of your environment: you establish a personal framework to deal with the slings and arrows.”

There’s a tension between the ways we try to impose control, and the wilder, less tameable aspects of ourselves. Can we know each other? Or even ourselves? What is the self?

Literal shadows in certain works provide a clue to the Jungian philosophy of self, the secretive, subconscious part of us that so influences our outward personae.

And then there are Hill’s figures which, as Larocque says, don’t depict the classic sense of a captured moment. They’re more like the freezing of an ambiguous, vaguely anxious gesture.

“The figures are involved in a great unknown,” he says, simply and rightly.

In Larocque’s erudite catalogue essay, he compares Hill’s figurative work to certain Edgar Degas prints, “where sometimes the viewer is caught in the uncomfortable role of accidental voyeur or illicit participant,” he writes. “They reflect spontaneity and are filled with immediacy, urgency, uncertainty and an rejection of exactitude.”

Suzanne Hill, Identity, 2016. Courtesy of the New Brunswick Museum. Photo: Rob Roy Reproductions.

Suzanne Hill, Identity, 2016. Courtesy of the New Brunswick Museum. Photo: Rob Roy Reproductions.

For Hill, the interplay between corporeality and consciousness is the crux of meaning.

“I think of the body, and the shadow, too, as the manifestation of whatever needs to be communicated.”

There’s also text—intriguing snippets she collects from pop culture, ancient philosophy and everything in between, working it into the layers of her art.

“Is it hard to make arrangements with yourself?” is a phrase she borrows from the Neil Young song “Tell Me Why.” (This could be the subtitle of the show.) There are quotes from Carol Shields, Plutarch and Leonard Cohen’s “Tower of Song,” among others.

When Hill finds a striking line, she’ll chew on it for ages, sussing out all its possible meanings.

“The words trigger or enlarge or clarify this intuition that I have that there’s something worth looking at,” Hill says. “It’s my job, because I don’t do words particularly well, I do pictures…to put it into body language.”

Atlantic Ballet Theatre of Canada performs Igor Dobrovolskiy’s Body’s Streams in Suzanne Hill’s exhibition “Singular” at the New Brunswick Museum. Photo: Courtesy of the New Brunswick Museum.

Atlantic Ballet Theatre of Canada performs Igor Dobrovolskiy’s Body’s Streams in Suzanne Hill’s exhibition “Singular” at the New Brunswick Museum. Photo: Courtesy of the New Brunswick Museum.

Body language is what Igor Dobrovolskiy deals in, too. The Ukraine-born choreographer, who co-founded Atlantic Ballet Theatre of Canada 15 years ago, first created his take on “Singular” as a solo work, evolving it into a six-minute piece involving the entire company.

The dancers, in tight leotards that echo Hill’s earthy palette, become like transubstantiations of Hill’s figures, slipped from their canvases and made living, casting looming, shifting shadows around the gallery, their individual and collective movements kinetic embodiments of Hill’s aesthetic and themes.

When Dobrovolskiy looks at Hill’s paintings, he can’t help but see dancers, even in the strange configurations she creates. Her work has inspired him to move his dancers in new ways.

“You think, What else can do you with the body to send a message, to tell philosophy?” he says. “How can you manipulate the body to tell some complicated message?”

Kate Wallace is an award-winning arts writer in Saint John, N.B. She is the founder of Pigeon, a creative communications company.

This article is part of Canadian Art’s year-long Spotlight on New Brunswick series, created with the support of the Sheila Hugh Mackay Foundation.

Suzanne Hill, Body Language I, 2014–2015. Courtesy the New Brunswick Museum. Photo: Rob Roy Reproductions.

Suzanne Hill, Body Language I, 2014–2015. Courtesy the New Brunswick Museum. Photo: Rob Roy Reproductions.