I think of art, at its most significant, as a DEW line, a Distant Early Warning system that can always be relied on to tell the old culture what is beginning to happen to it. —Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media (1964)

The physical entity of the DEW Line—suffused as it was with the simultaneous idealism of Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes and the paranoid fervour of a cold country defending itself from an even colder war—is a provocative image for the role of the artist. In some ways, McLuhan’s metaphor has never seemed more literal, as planetary warming becomes one of the most pressing, and largely ignored, issues of our time. And while the idea that art could be such a tangible harbinger of social change might be something of an anathema in contemporary art thinking, it is also precisely the thing that makes the vision behind Cape Farewell so compelling and idiosyncratic.

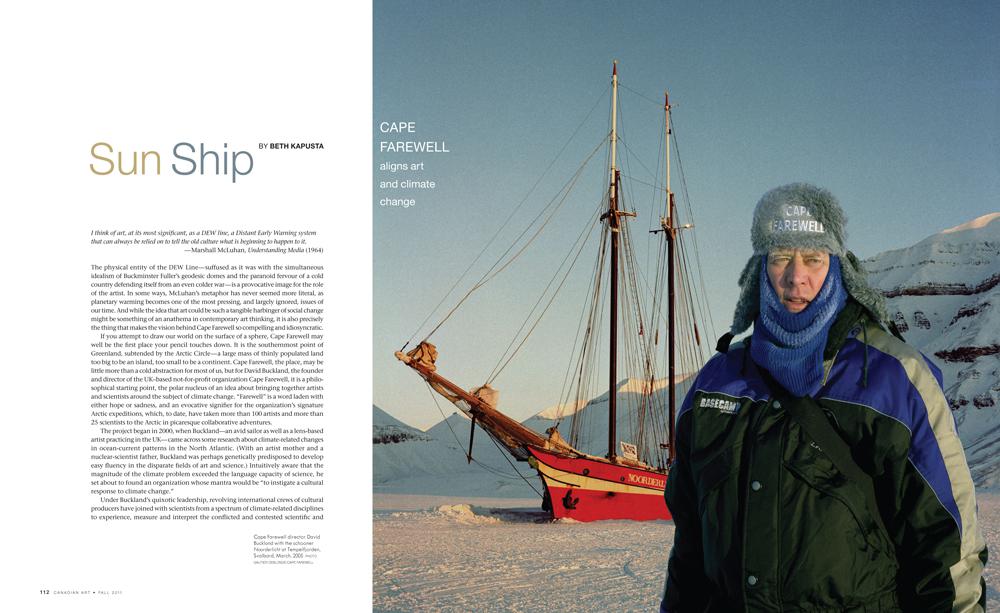

If you attempt to draw our world on the surface of a sphere, Cape Farewell may well be the first place your pencil touches down. It is the southernmost point of Greenland, subtended by the Arctic Circle—a large mass of thinly populated land too big to be an island, too small to be a continent. Cape Farewell, the place, may be little more than a cold abstraction for most of us, but for David Buckland, the founder and director of the UK–based not-for-profit organization Cape Farewell, it is a philosophical starting point, the polar nucleus of an idea about bringing together artists and scientists around the subject of climate change. “Farewell” is a word laden with either hope or sadness, and an evocative signifier for the organization’s signature Arctic expeditions, which, to date, have taken more than 100 artists and more than 25 scientists to the Arctic in picaresque collaborative adventures.

The project began in 2000, when Buckland—an avid sailor as well as a lens- based artist practicing in the UK—came across some research about climate- related changes in ocean-current patterns in the North Atlantic. (With an artist mother and a nuclear-scientist father, Buckland was perhaps genetically predisposed to develop easy fluency in the disparate fields of art and science.) Intuitively aware that the magnitude of the climate problem exceeded the language capacity of science, he set about to found an organization whose mantra would be “to instigate a cultural response to climate change.”

Under Buckland’s quixotic leadership, revolving international crews of cultural producers have joined with scientists from a spectrum of climate- related disciplines to experience, measure and interpret the conflicted and contested scientific aesthetic dimensions of this northern landscape. Buckland’s definition of “cultural producer” is pretty catholic—participants have included comedians, journalists, students, beat-box artists, musicians, architects, filmmakers, poets, theatre and opera writers, dancers and, of course, writers: Gretel Ehrlich (2003), Ian McEwan (2005) and Vikram Seth (2007). McEwan’s most recent book, Solar, at times almost satirizes his Cape Farewell experience, but his misanthropic scientist-hero captures its philosophy pretty accurately: “Beard would not have believed it possible that he would be in a room drinking with so many seized by the same particular assumption, that it was art in its highest forms—poetry, sculpture, dance, abstract music, conceptual art—that would lift climate change as a subject, gild it, palpate it, reveal all the horror and lost beauty and awesome threat and inspire the public to take thought, take action, or demand it of others. He sat in silent wonder. Idealism was so alien to his nature that he could not raise an objection. He was in new territory, among a friendly tribe of exotics.”

Last year, at an exhibition of Francis Alÿs’s work at Tate Modern, I was struck by a piece of the artist’s writing, which speaks directly to the changing role of the artist in our time: “…how can art remain politically significant without assuming a doctrinal standpoint or aspiring to become social activism?” He further interrogates the capacity of an artistic intervention to translate social tensions that change the “imaginary landscape” of a place or to provoke transgressions that precipitate the abandonment of assumptions, and thereby “bring about the possibility of change.” Alÿs wrote these words to make sense of his intervention into the city of Jerusalem’s Green Line in 2004. It is not a far stretch to see how well his words describe the intent and optimism behind the Cape Farewell project.

Many of Cape Farewell’s visual artists have provided rich output for a number of ongoing expeditions, contributing to shows such as “eARTh,” which Buckland curated last year at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, as well as “U-N-F-O-L-D,” an exhibition now appearing at Parsons The New School for Design, before moving on to Beijing (Vienna, London, Newcastle, Falmouth and Chicago are also on the tour). Buckland’s own eclectic, lensbased work ranges from portraiture to projections of pregnant women and pregnant phrases onto glaciers and icebergs. However, the process of feeding and managing Cape Farewell and fulfilling the associated leadership, curatorial, convening and fundraising roles he has assumed over the last ten years has somewhat altered his art career in the conventional sense, often taking him deep into curatorial territory.

As an architecture critic with an interest in culture’s role in social change, I got involved with the Cape Farewell project after participating in a social visioning session sponsored by the Musagetes Foundation in 2009, in which Cape Farewell also participated. I was then invited to take part in the 2010 Arctic expedition that made its way north from Longyearbyen and up the west coast of Svalbard.

On this trip aboard a century-old sailing schooner known as the Noorderlicht (“northern light,” in Dutch), I was immediately struck by the familiar, evocative power of all things Arctic. This power has historically spellbound Canadian artists like Lawren Harris and Joyce Wieland; the latter spoke of a quality of light and a serene scale that was “perhaps of a more certain conviction of eternal values.” And while that strange northern light still holds its magic—I spent the better part of a day on board writing about it and trying to understand its phenomenological allure—it is with questions rather more existential in mind that Buckland leads artists north, to what he likes to call “the front line of climate change.”

A handful of Canadians made the 2010 journey—myself, the artist Iris Häussler and the architect Bob Davies. (Canadian alumni include the artist Brian Jungen, the musicians Martha Wainwright and Feist, the Cape Breton–based Gaelic singer Mary Jane Lamond and the writer Yann Martel, plus a high school student from every province in 2007.) The 2010 expedition had a uniquely Slavic bent. It included several Russians: a playwright, a writer, a curator, a biologist and a visual artist, Leonid Tishkov, whose Private Moon, an illuminated crescent photographed in various cities, became almost another character on the journey.

Some days, we observed, or participated in science experiments that mapped changes in the Greenland current, or trolled for tiny primitive life forms to see how they were surviving the warmer water temperatures. Other days, we experienced timeless silences while traversing glacial deposits that resembled primordial construction sites, or took in the guileless curiosity of Arctic foxes and the awesome presence of blue whales. For our particular crew, however, it was a short but terrifying entrapment in the ice, and a narrow escape—the result of the melting polar ice cap’s second-worst year in recorded history—that was sufficient to drive home the seriousness of the science. As we considered this deeply experiential, even existential, knowledge, a hungry polar bear circled the boat, providing an almost Shakespearean interlude of comic relief.

During our expedition, Häussler drew incessantly (an exercise she describes as “sketching in a panic”). She’d attempt to record the movement of the mercurial water, the feeling of wonder at what swirled below the sailing vessel as we progressed north of the 80th parallel—and was infamous in the group for her fascination with the “birth canals” of the melting glaciers on which we walked. She’d thrust her hand deep into their cavernous depths, savouring the disembodied experience of feeling, but not seeing, such an extraordinary sculptural condition.

Although Häussler does not imagine these sketchbooks as finished artworks, she feels that the fictional characters at the heart of her haptic conceptual practice cannot help but be influenced by these experiences. She cannot yet say how exactly that might manifest in her work, which generally remains very secretive until it becomes fully public. (Participating in the Cape Farewell experience entails no imperative to produce. Sometimes, the art takes form spontaneously; sometimes, it happens many years later, or not at all. During his 2005 trip, the UK–based artist Antony Gormley collaborated with the architect Peter Clegg on a trio of sculptures called Three Made Places. Feist produced a piece of Super 8–mm film, which featured prominently in Peter Gilbert’s 2009 documentary, Burning Ice).

Historically, many Cape Farewell artworks strive to make sense of the impossible magnitude of the sublime Arctic landscape and the even vaster conceptual landscape of climate change, bringing a human scale to both while foretelling challenges. We bore rapt witness to simultaneous grandeur and loss: the spectacular crashing of glaciers thousands of years in the making, 40 years in the melting. But if the Arctic’s palpables are powerful, its invisibles are even more profound. To witness this landscape only at face value would overlook urgent points: Arctic temperatures are warming at about twice the rate of the global average, and the melting of the polar ice cap will have a profound effect on the rest of the world. The Arctic will be increasingly opened up to further exploitation and, perversely, to the extraction of fossil fuels, whose carbon emissions are the primary culprit of the anthropogenic climate change that is causing the ice cap to melt in the first place.

The indelible traces of human exploitation even at this most remote place on Earth—where compasses stop working and the North Star shines overhead—tell an ominous story about human nature. The killing fields where thousands of walruses were slain for their blubber. The blackened town of Barentsburg, permanently defined and defiled by the systematic resource exploitation of coal extraction. Even the curious remains of a book we find frozen into the permafrost, on a glacier hundreds of miles from any human inhabitation, bespoke an enigma, its chapter title ominously and somewhat surreally declaring, “Capable Women Can Make a Meal without Food.”

It feels inevitable that exploitation will colour the future even more dramatically, as the melting of the ice cap and subsequent accessibility of oil reserves will make the contested ownership of this resource a significant political issue. The words and art of Wieland and her classic kiss-print lithograph The Arctic Belongs To Itself (1973) seem prescient, especially in view of recent Cape Farewell–inspired projects like Alex Hartley’s ongoing work Nymark (Undiscovered Island), a photographic piece that has involved finding, naming and claiming a “new” island whose presence had been revealed by the retreat of a glacier; the piece is currently being expanded and reworked for the 2012 London Cultural Olympiad.

In words, it is Gormley who has most eloquently captured the changing role of art at the heart of the Cape Farewell vision. At the “10” workshop, a Cape Farewell event convened last year in London, he posed the following question: “Is it possible for survival to become central to the inspiration and purpose of art?” He went on to explain: “The earliest bits of human material culture are deeply embedded with a sense of continuance, of art being a tool for survival. And that model is one that we have to return to, and I think it does mean that we have to in some sense jettison our 18thcentury Enlightenment idea about culture. Culture can no longer identify itself as distinct from nature, and we have to put the notion of human survival back as the central focus and purpose of art.”

For a video of Antony Gormley and Peter Clegg working on their collaborative sculpture Three Made Places, go to canadianart.ca/capefarewell

This is an article from the Fall 2011 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.