Slut Island is a feminist-queer-DIY music festival that was founded in Montreal in 2013 primarily for performers and audiences who identify as women, trans*, gender fluid, non-binary queers, people of colour, and, as its co-founders Frankie Teardrop and Ethel Eugene say, “freaky babes and underrepresented folks who hold anti-oppressive values.”

Accordingly, Slut Island aims to increase the visibility and appreciation of marginalized performers, and to be inclusive of an audience by striving to ensure safer, harassment-free spaces. This year, its wide-ranging programming includes Oakland-based electro-pop artist AH-MER-AH-SU, New Orleans Trap goddess Delish, and Nino Brown, co-founding DJ of the beloved Toronto queer dance party Yes Yes Y’all, among many others.

I interviewed Ethel Eugene (A.K.A. Samantha Garritano) about the impetus to set up a queer, feminist DIY haven like Slut Island, how the presence of active listeners can make venues safer spaces, and how the event posters she designs with representational drawings of the performers are tools for advocacy.

Merray Gerges: The name of the festival itself sounds similar to, and may be a dig at Sled Island [an annual independent Calgary-based music and art festival], but Slut Island is a response to the general lack of festival programming that prioritizes women-identifying people.

Ethel Eugene: Sled Island isn’t actually relatively that bad, so we don’t wanna rip on it too much. We’re just into the “sled”-“slut” wordplay. But I don’t think white dudes alone are enough content for a festival anymore.

MG: Prominent festivals aren’t trying hard enough to be inclusive. They claim that booking women isn’t as profitable as booking men, that there are fewer women to choose from, or that the women approached were “busy.” Even after all the recent think pieces about blatant exclusion, by now it should occur to festival organizers, who tend to be cis-hetero-white dudes, to program beyond people who are just like them.

EE: Frankie and I have been involved in the Montreal music scene for years and have been forced to accept that women and queers don’t hold the reins over anything. We’re often in positions where we’re reporting to and/or being managed by dudes. You just play a show and hope you’ll never be in a situation where you wanna call out sexism (like a sound tech being condescending or mansplaining your instrument) because there probably won’t really be an outlet for that and that makes it hard to participate comfortably. You want to have the space to call that out and know that people will take you seriously.

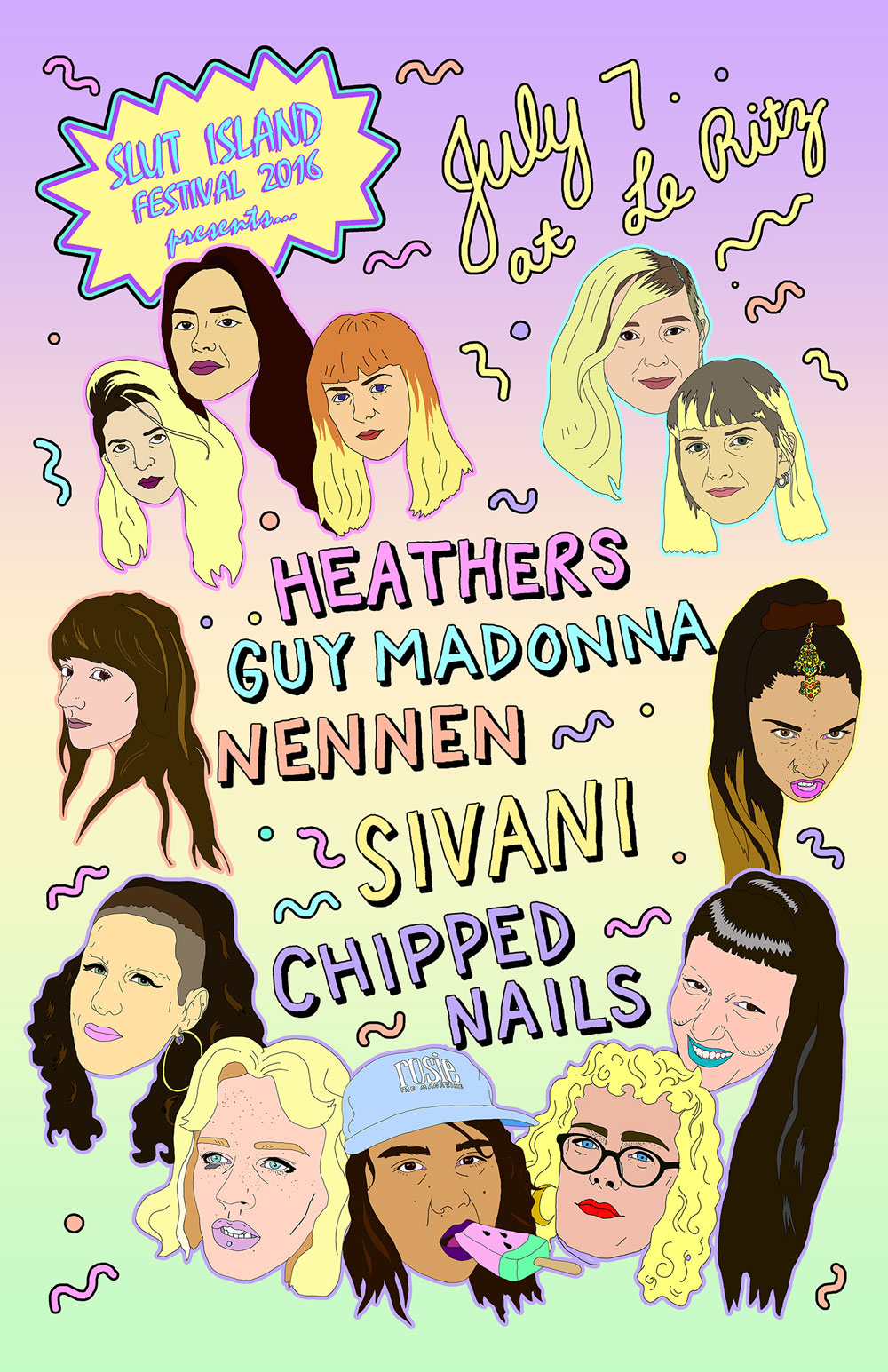

A Slut Island poster by Ethel Eugene. Eugene strives to draw images of the performers on the posters to “show how much we respect and celebrate these artists.”

A Slut Island poster by Ethel Eugene. Eugene strives to draw images of the performers on the posters to “show how much we respect and celebrate these artists.”

MG: How is Slut Island a safe space?

EE: We can’t claim safe space because that’s impossible to guarantee. We can’t control people’s behaviour, let alone an entire environment, enough to [qualify] a space as “safe.” More than ever, this year we’re [prioritizing] the on-site presence of people trained in active listening. In the event that someone does feel unsafe, which could mean a wide range of things, they have someone to talk to who cares. Our festival is for and by queers and people who face varying degrees of discrimination, harassment and aggression on the day-to-day, so naturally those are the people who may not feel comfortable in public spaces, the people who may have higher levels of social anxiety triggers. People who aren’t cis-hetero white dudes have probably had to deal with shit that makes public spaces and events feel more daunting.

MG: What are active listeners and how are they trained?

EE: Active listeners are people who deal with uncomfortable situations that people don’t feel equipped to deal with on their own. At Slut Island Festival, they’re identified with glow sticks on their wrists. There’s a notice at the bar and an announcement onstage that says that if anyone is feeling unsafe, there are people on-site who can help them. Maybe it’s people who are inebriated and having a hard time, maybe it’s someone who is feeling triggered by [the presence of someone who’s assaulted them in the past or someone who’s harassing them at the time]. Active listeners are trained to be alert and engaged and to respond with care. If a person is not trained in active listening or harm reduction, they might call the cops or something, which is obviously the shittiest idea ever. There are things that we could do to help each other without involving cops. It may not make it a total “safe space,” but at least it makes it safer.

MG: Are all the venues accessible this year?

EE: Yes, yes, yes. In our first year we put out a disclaimer that was like, “No racist, sexist, homophobic, transphobic, fatphobic, sizeist, ableist behaviour will be tolerated at this party. If this behaviour is reported to us you will be asked to leave.” And then someone called us out on the Facebook event and was like, “Cool. Your party is up three flights of stairs. So that’s ableist.” And we were like, “Oh, shit, well that’s a reality check.” It was harsh but it was a real call to action. We all know how call-out culture can be so intense, but I think part of being an organizer at Slut Island is being ready for criticism, because you’re in the public and you’re making all these claims [of inclusivity].

If you’re going to try to be radical, you need to be open to criticism and be prepared to learn new things and adjust yourself accordingly. Accessibility should be a given, a priority, when we’re throwing parties of this nature. Montreal has an utter lack of accessible venues, which has been a really big obstacle when we’re trying to keep costs low and use spaces that are more easily available to us. However, we are pleased to announce that this year, both hosting venues, Le Ritz P.D.B. and Casa Del Popolo, are accessible.

We also found out two days ago that we got funding this year for the first time ever. We used to pool the money together at the end of the festival and pay everyone equally, regardless of their show’s attendance. Now we can actually pay people who are playing this festival, which is by and for underrepresented people, as if it was a super official festival. It feels so good to be like, “Actually, we can give you the respect and treatment you deserve that you may not receive if you were playing a mainstream festival; we see you, we care about your music, we think that you’re rad, and we also pay you as though we were in the ‘normal world’ where we’re getting the recognition that we deserve. Yay!”

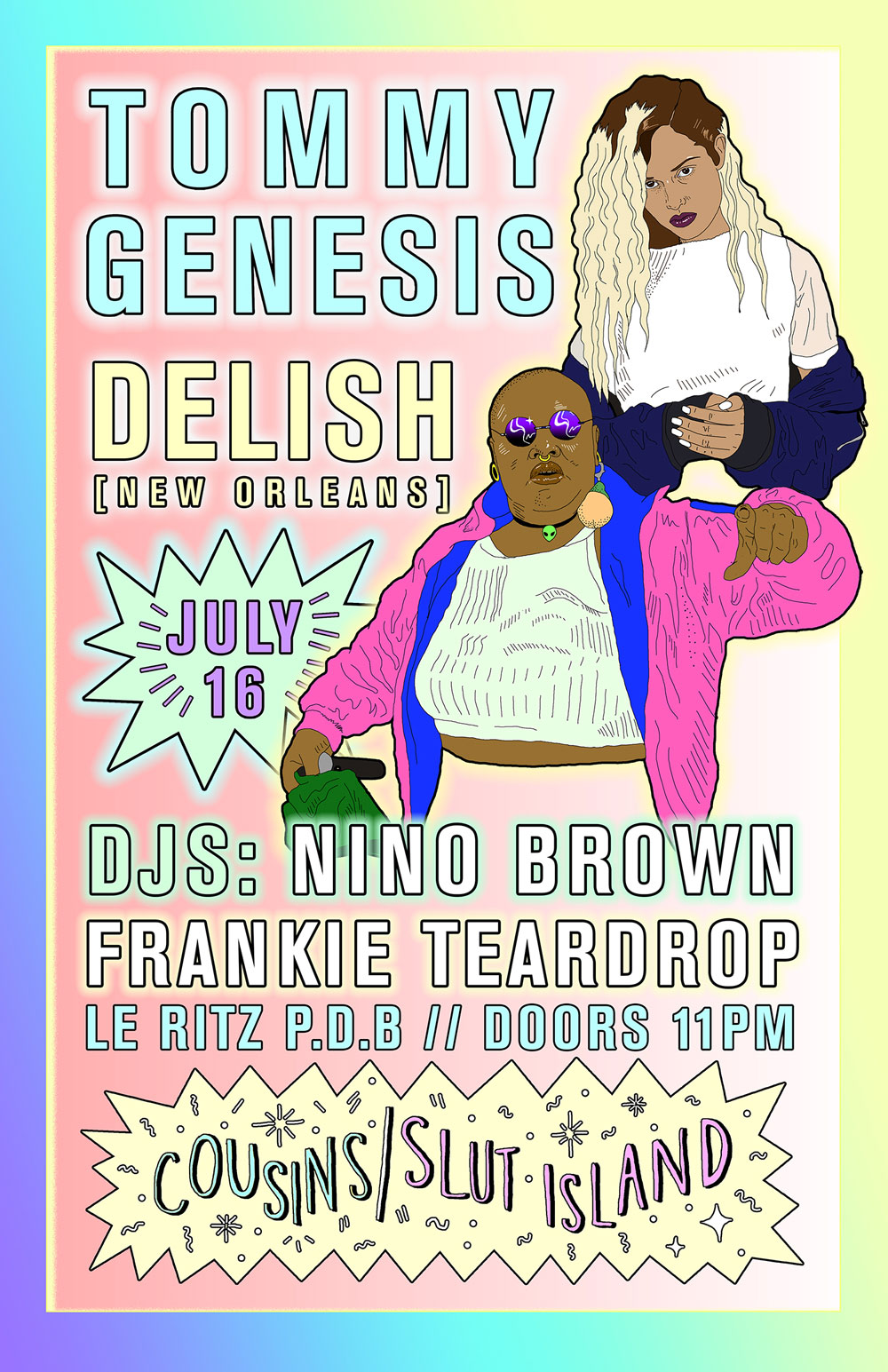

A Slut Island poster by Ethel Eugene celebrates a festival that aims to be a queer, feminist DIY haven.

A Slut Island poster by Ethel Eugene celebrates a festival that aims to be a queer, feminist DIY haven.

MG: How do you curate performers when political alignment is a priority?

EE: Frankie and I are the sole curators and our interests are wide-ranging. We both play in punk bands, and Frankie is a techno DJ, so we naturally have some personal taste biases that we set aside for the curatorial process, which I believe is reflected in the wide range of musical genres in the festival line up.

The number one question in the application process is, “Why do you think this festival is for you?” We ask that first, and then we listen second and we’re like, “Does their music feel good? Can I groove to it? Would this make a good show?” We don’t want to just throw people together in a tokenizing way without placing importance on what they actually produce. We prioritize people who need a space like Slut Island while carefully constructing a cohesive and pleasurable evening.

MG: The variety of the line-up is a gesture of inclusiveness towards your audience, but you’re also mindful of access to capital, or lack thereof. Most of the shows are PWYC [pay what you can], right?

EE: We suggest a $10 donation but no one is turned away for lack of funds and we’re not willing to ever change that.

MG: I see the posters as a manifestation of your politics and all of these things you’re striving to do, how you want to be welcoming and inclusive.

EE: That’s the goal. All of the drawings in the posters are from reference images I’ve taken myself or from press photos performers have sent. I want to show how much we respect and celebrate these artists, so they’re kind of a labour of love. I assume it feels good to play a show where the poster features a custom made portrait of you. I do a lot of research and listening to get a sense for the people I’m representing on these posters.

It’s pretty amazing to see them IRL, post-Photoshop. I would say they’re less inviting in print because the RGB to CMYK shift makes them duller and my colour palette is extremely intentional. I spend 15 hours on the posters and Frankie spends countless hours wheat-pasting them all over the city. We both have to deal with the misery of seeing them taken down the next day. But that’s what happens when you put art in a public space. You lose control of it and it’s not yours anymore.

I don’t have a graphic design background, so I feel like a lot of my posters are kind of whack.

Ethel Eugene spends approximately 15 hours on average on each poster, and Frankie single-handedly wheat pastes them all over the city.

Ethel Eugene spends approximately 15 hours on average on each poster, and Frankie single-handedly wheat pastes them all over the city.

MG: You’ve told me that you’re going for a camp-80s, hyper-ice-queen, candy-femme aesthetic.

EE: I feel like I perform every day, and so many gender-freaks feel that way too. The posters are almost jokes, but they’re so labour-intensive. It’s how I feel about getting dressed. I’m making fun of it, but I’m taking it really seriously; they’re kind of sarcastic, but hard to dismiss.

I’m also inspired by Clay Hickson’s graphic drawings and gradients, and Lisa Czech’s punk show posters that are based on observational drawings of tropes in her community.

MG: Even though some of them get taken down, the wheat-paste means that the ones that don’t can last through a season, so that they have this lifespan beyond the date of the show.

EE: I love that about show posters, too. When the date has passed, they’re just works of art. It’s not actually advertising anything anymore. There are 10 posters this year, and they are the portrait of Slut Island Festival 2016, of the queers and freaks that I’m so excited to be collaborating with. They’re taking up public space. Of course, we’re advertising the shows, and of course, we want them to be well attended, but more than that, I’m advertising queers and people who I want to have more visibility. I’m making their names visible with these super-meticulously crafted images that demand attention.

MG: So the images aren’t just promotional; they’re a historical record, too.

EE: For sure. They’re celebrating these people. Like, “Hell yeah, I want your names pasted all over this city. You rule.”

Slut Island launches in Montreal on July 7 and lasts till July 16. Both hosting venues, Le Ritz P.D.B. and Casa Del Popolo, are accessible.

Merray Gerges is Canadian Art‘s current Editorial Resident. She’s on Snapchat, Instagram and Twitter as @merrayrayray.

A Slut Island poster by Ethel Eugene, who’s inspired in part by Clay Hickson and Lisa Czech.

A Slut Island poster by Ethel Eugene, who’s inspired in part by Clay Hickson and Lisa Czech.