For the past two-and-a-half decades, art dealer Simon Blais has had a steadfast presence on the Montreal art scene. To mark that silver-anniversary moment, Galerie Simon Blais recently mounted a pair of exhibitions: one a sort of fantasy collection of works by major gallery artists—many of them iconic Quebec modernist painters—the other a forecast of key works by some of the gallery’s younger crew of contemporary artists. Both shows closed last weekend to make way for the gallery’s next feature exhibition, which highlights the work of Isabelle Guimond, winner of the 2014 Sylvie and Simon Blais Award. The prize, initiated in 2009, is a testament to Blais’s forward-looking savvy in the business of art, not to mention his keen eye for rising talent. Here, he speaks with Bryne McLaughlin about where the gallery began, what changes he’s witnessed over the years, and how it all might develop in the next quarter of a century.

Bryne McLaughlin: Congratulations on 25 years. To start, can you expand on what you’ve done with the gallery in the past couple of decades and on what you’re planning for the future?

Simon Blais: I launched the gallery back in 1989. I was 33 then, and I specialized in the beginning in works on paper. What we did this summer in June and July is organize two shows that speculate on where we’ve been and where we’re going.

In the main gallery, we had “1989–The Improbable Exhibition,” which brought together paintings, drawings and photographs that could have been shown when they were freshly created in 1989 by artists that we’ve represented from the start or who have joined the gallery over the years. That includes major Quebec artists such as Jacques Hurtubise, Marcelle Ferron, Jean Paul Riopelle, Jean McEwen, all of the main figures both from the Automatistes and their followers—including Guido Molinari, Irene Whittome, Louise Robert and Catherine Farish—as well as photographers like Michel Campeau and Serge Clément. We picked from their inventories of works from 1989. The big tickets, you know.

In the other gallery was “2014–Here and Now,” which featured our roster of younger artists such as Marc Séguin, Yann Pocreau, Carol Bernier and Éliane Excoffier. Excoffier’s work is about the female body. In every situation, she uses vintage cameras and photography techniques, and she is just now beginning to use digital cameras. It’s magnificent work.

BM: So you had blue-chip modern painters rubbing shoulders with contemporary artists. Did that mix reveal anything particularly significant, or even surprising, about where the gallery started from and also where it’s headed in the next 25 years?

SB: You know, there are now two sides to the gallery: the modernist work and the contemporary work.

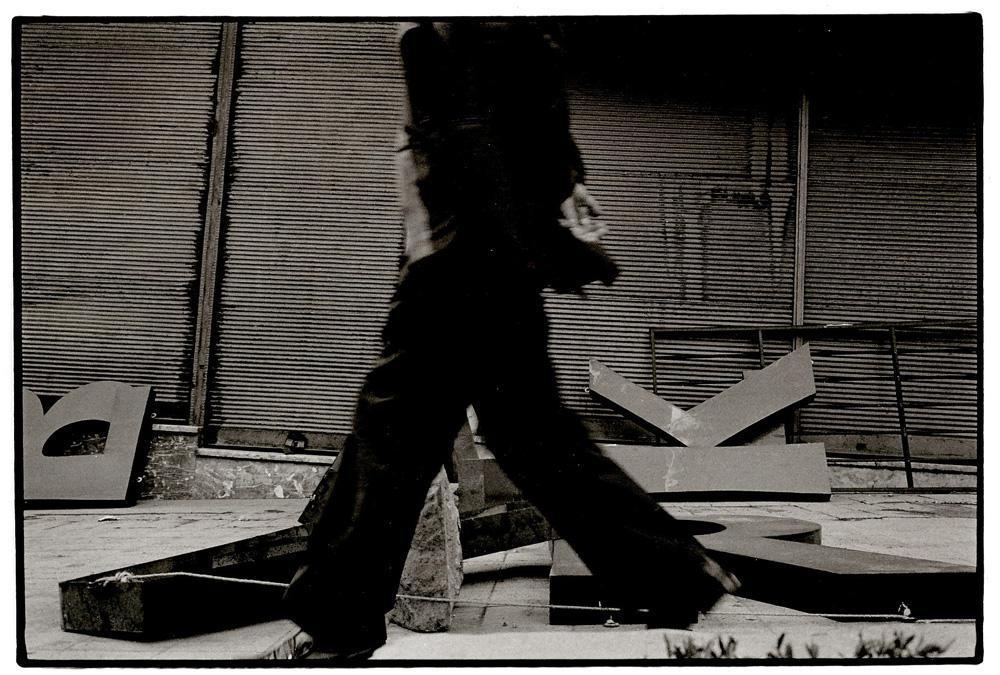

What unites these two eras is photography, works by guys like Campeau, who has been friends with Serge Clément and Bertrand Carrière. They were all photographers using reportage or documentary photography in black and white. We started with them and for us they still represent a launch into the future. These guys are in their 60s—or nearing them—but they still have so much to say. Of course, back in 1989 they had not touched digital, and not even colour. What they are doing today? They all work in colour and most use digital cameras.

BM: I guess you must often find yourself in that unusual, but not unprecedented, situation as an art dealer—having a foothold in the past, but also constantly looking to the future?

SB: Yes, absolutely. We’re always working for the future. It’s been 25 years and we know we want the gallery to keep going for decades more, if possible. We have a very nice group of gallery artists. But we have to keep finding a new way. So, for example, we invite one young artist each year to add to the gallery roster.

BM: When you think about the past two-and-a-half decades, what kinds of changes strike you most in the business of art dealing? Not only in Montreal, but also generally.

SB: Huge changes. I’ve always catered to Quebec collectors, but now more and more to a national clientele as well, in Ontario and the Western provinces. This is mostly with the modernist work.

In contemporary work, it’s mainly photography. The rise of photography, and the fact that we decided to work with these photo artists, is the major change for us in the past 25 years. When I opened, I had no photographers, it was exclusively works on paper. But the importance that photography took in the museums and the contemporary art world, it was important to follow that. So we’ve found our own ways of presenting and including photo-based artists.

It’s only been 12 or 15 years since digital photography really came of age. Now there’s almost nothing else being presented in museums and at fairs and biennials. People now see photography as just as important as any other medium.

Just 15 years ago, with the exception of the major figures, it was accepted that anyone could do photography. It was not taken seriously. Nowadays, we include photography within our group shows as if there was no difference. The photos are mixed up with painting and sculpture. Trust me, it’s all intermingled.

BM: Do you see this intermingling of works in your gallery roster as an opportunity to cross over your clientele? That is, to introduce younger audiences and collectors, who might be more inclined toward contemporary work like digital photography, to the blue-chip modernist painters?

SB: Yes. I’ve always worked that way. At the gallery you can see so much in terms of modernistic work, back to 1945. Every time you walk into the gallery, it is a course in art history. An art student could spend hours here and learn how the rise of abstract painting made its way in Quebec with the inventory we have.

And it goes the other way, too. It’s been 20 years now that I’ve presented modern art shows. That’s always attracted clientele that was not prepared to look at cutting-edge contemporary work, but eventually they’ve moved their sights from the modern works to the contemporary.

BM: How about you? How has dealing with and living with these works over the years affected you?

SB: Listen, I’ve become a passionate dealer, connoisseur and collector. And as much as I’ve become a huge collector of contemporary work, both in painting and photography, the fact is, I’ve become like an art historian myself. By talking and meeting with these older figures, you learn so much. It puts things in perspective.

Knowing that much about the history of art here in this country, you learn how to judge, evaluate and appraise works by younger artists. You may be able to steer them in the right direction, to avoid the traps of repeating mistakes and to be conscious of what they are doing.

It’s probably the case with most decent contemporary art galleries: the huge majority of our artists are well trained, they all have bachelor’s degrees in studio art or art history. It’s amazing how that has changed. Twenty-five years ago there were still lots of self-taught artists, which is something that’s almost unheard of nowadays.

BM: Yes, I suspect there’s pressure for dealers, too. You almost have to have a graduate-level knowledge of art history to properly do business. Lastly, what were your ambitions when you started? Could you have predicted how the gallery has changed and grown in the past couple of decades?

SB: No, no. Never. I just wanted to make a living. Prior to opening my gallery, I had worked for 10 years at a print gallery in Montreal. I just wanted to be on my own. I knew I loved the idea of meeting people and promoting works of art, but I was very green and naïve in the prospects the future would bring.

Let’s say I found out I was an entrepreneur when I opened up in 1989 and there was a huge financial crisis in 1990. It was such a setback. For five years, nothing was happening. Business was dead and we had to be very, very creative to survive. That’s when I found out I was an entrepreneur. I just wanted to make a decent living, a fun living. But it was a fight for survival.

Trust me, though, the best way to run such a business venture is by not knowing exactly what you’re going to do or where you’re going to be 10 years from now. You have to be creative, you have to evolve, and you have to find new solutions. Now with the digital era that we are in, one has to keep moving ahead and find new opportunities. So things like websites and social media, for example, have become very important.

BM: So you’re constantly open to new ideas.

SB: Yes. I have a group of colleagues that is mixed up of young and older staff. I’m 57; my oldest assistant, François, is a couple of years younger; and the ages go down to 30 years old. Hopefully my son will join us; he’s in his early 20s. You have to keep on top of the crest of the wave if you want to maintain success.

Even though we are an art gallery that is now 25 years old—and that’s almost very old!—you have to remain fresh, and the only way to achieve that is by having younger staff, younger artists and younger ideas.