During a recent conversation on the topic of the artistic relève, fellow Acadian artist Alisa Arsenault expressed to me her lasting impression that Moncton “is a screenprinting city.”

Being a screenprinter myself, as well as a board member at Centre d’estampe Imago and codirector at the Galerie Sans Nom, this statement certainly got me thinking.

From an historical perspective, Moncton is a city that has fostered contemporary art practices, having served as a backdrop for most of the major developments in contemporary Acadian art since its birth at the Université de Moncton (UdeM) in the 1960s.

Although not a major breakthrough in itself, screenprinting’s arrival in Moncton coincided with a cultural renaissance that would largely define the late 60s and 70s Acadian experience. Its subsequent disappearance from the Acadian artistic landscape in the years that followed would only serve to reinforce its comeback in the early 2000s, when artists began assimilating it into the interdisciplinary art practices that we know today.

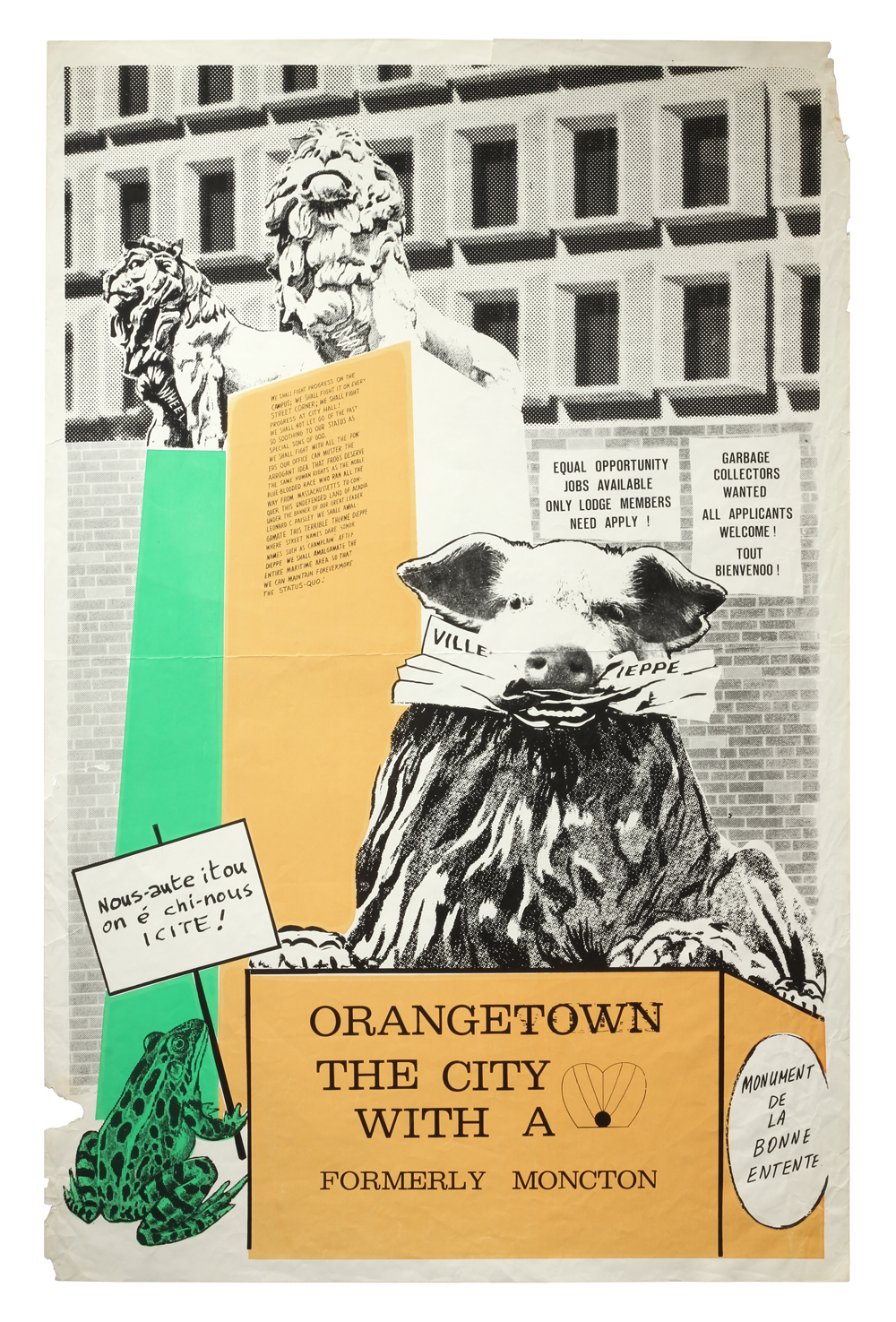

If Moncton ever was a screenprinting city, it most certainly began its transformation in the politicized spirit of the UdeM student protests that took place in February 1968. Consider the following image of a pig’s head resting on a lion’s statue:

Anonymous, Untitled poster, ca. 1968. Screenprint on paper. Photo: Rémi Belliveau.

Anonymous, Untitled poster, ca. 1968. Screenprint on paper. Photo: Rémi Belliveau.

Commercially screenprinted circa 1968, this large poster highlights the key issues that fuelled a heated conflict between the francophone students of the Université de Moncton and the City of Moncton’s then anti-francophone mayor, Leonard C. Jones.

Most famously captured in Michel Brault and Pierre Perrault’s documentary L’Acadie, L’Acadie?!?, the events surrounding the student protests of February 1968, although ultimately unsuccessful, ushered in a new age of Acadian culture and gave birth to a generation of young, politically engaged francophones that would include the first contemporary Acadian screenprinter, Herménégilde Chiasson.

By the end of the winter 1968 session, the student movement in Moncton had come to a grinding halt, with key leaders being banned from the campus, and many others leaving the city for good.

It was in this grim atmosphere that news came from overseas in May, announcing that protests had erupted between students and police in France. Many Acadian students, including Chiasson, followed these events closely, expressing their solidarity with the French students who were protesting on a much larger scale, which included an independent press and a massive production of screenprinted posters.

It was these posters that first motivated Chiasson to enrol in print classes at Mount Allison University that summer, where he learned enough about the screenprinting process to share it with fellow artists in Moncton. The first run of screenprints by Acadian artists were printed in a garage attic in 1969 and included works by André Thériault, Roméo Savoie, Francis Coutellier, Edward Leger and, of course, Chiasson.

The experiment would ultimately bring Coutellier, then professor of painting and ceramics at UdeM, to seek out professional aid in printing more sophisticated editions, establishing an initial point of contact with the commercial printer Bob Landry, who eventually provided the Fine Arts Department with its first one-arm squeegee table.

While these experiments were going on, another professor in the department was also developing an interest for screenprinting as a possible way of bringing photographic images into his sculptural canvas works. Claude Roussel, then professor of sculpture at UdeM, was working on a series of relief canvases based on the theme of lunar exploration when, in the summer of 1969, the Apollo 11 spacecraft successfully landed on the moon.

Photographs of the moon landing immediately began circulating in special edition magazines and newspapers, prompting Roussel to select one for incorporation in the series. After ordering a screen from one of the local commercial print shops, Roussel hand-printed an iconic photo of Buzz Aldrin onto bare canvas using red ink, working the rest of the embossed canvas with blue and orange paint.

The resulting work, L’homme sur la lune, was the first known screenprint on canvas by an Acadian artist, and thus stood out in his lunar series when it was shown for the first time in “La lune et ses effets,” a solo show at the Galerie d’art de l’Université de Moncton in 1970. (This work was also included in a recent retrospective of Roussel’s relief canvases and shaped plastics called “Éros et transfiguration,” curated by Paul Édouard Bourque for the Galerie d’art Louise-et-Reuben-Cohen.)

Other works outside of the series were created using the same screen, including a cube that combined the three-dimensionality of Andy Warhol’s boxes with the two-toned approach of Warhol’s Ethel Scull portraits. That same year, Roussel began experimenting with vacuum-shaped plastics, a technique that he merged with screenprinting in 1975. By this time, the medium had become part of the Acadian art lexicon and was being taught at the UdeM Fine Arts Department.

Claude Roussel, L’homme sur la lune (cube), 1970. Screenprint on wood. Photo: Rémi Belliveau.

Claude Roussel, L’homme sur la lune (cube), 1970. Screenprint on wood. Photo: Rémi Belliveau.

Herménégilde Chiasson was the first to teach the screenprinting process at UdeM—in 1973, after having spent the prior two years developing minimalist prints at Mount Allison University. By his own account, the course was a complete disaster, with students standing in puddles of paint thinner, brandishing ink-soaked rags, most of them smoking cigarettes while working in an ill-equipped studio that relied on one small ventilation duct.

It was about this time that Quebecois artist Louis Desaulniers, author of L’art de la sérigraphie, arrived at the department claiming that when he was done teaching, students would be able to eat off the floor.

Nevertheless, Chiasson kept screenprinting throughout the mid-70s, beginning work on a series of politico-Acadian prints in 1974 that were set aside when he left for Paris in 1975.

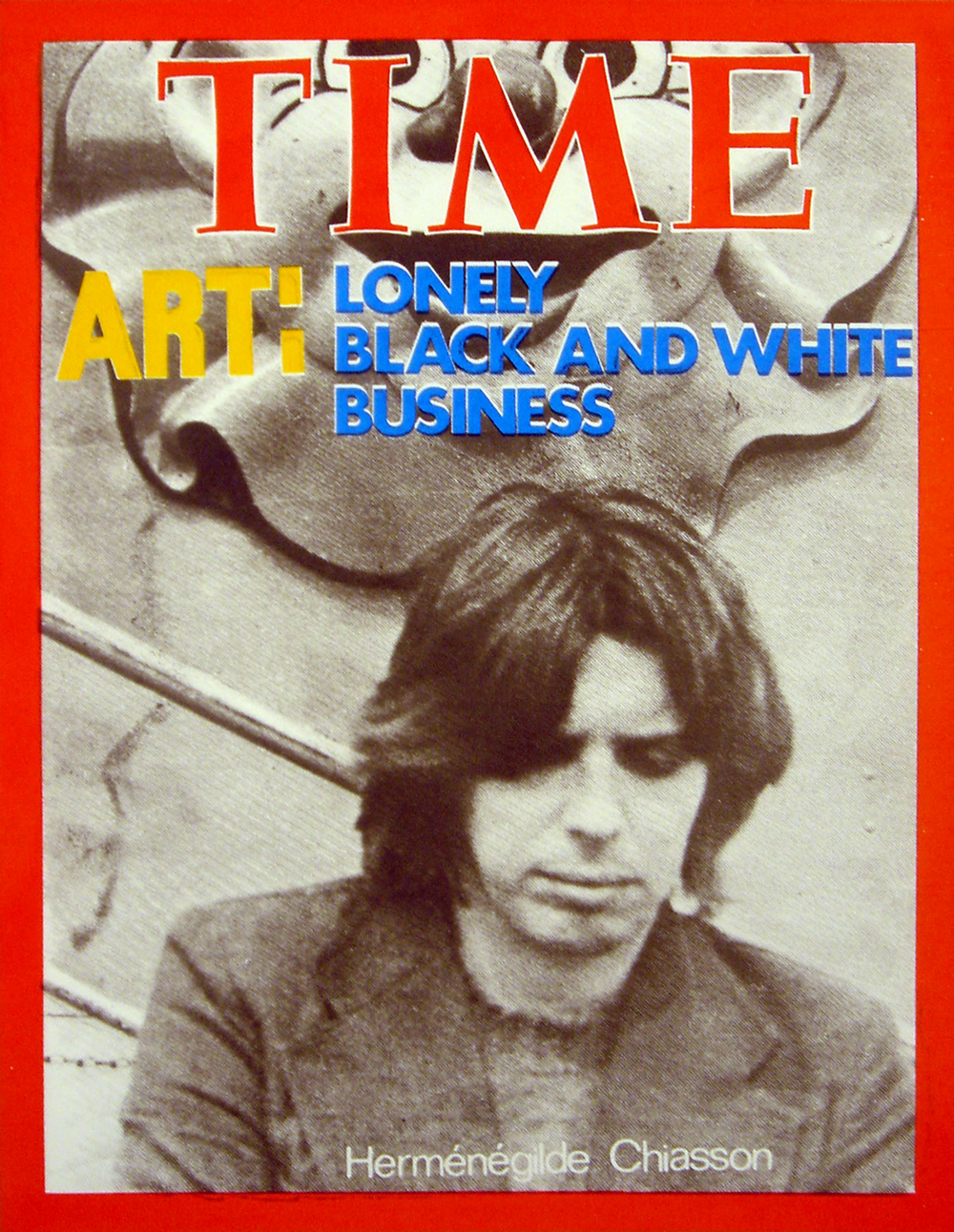

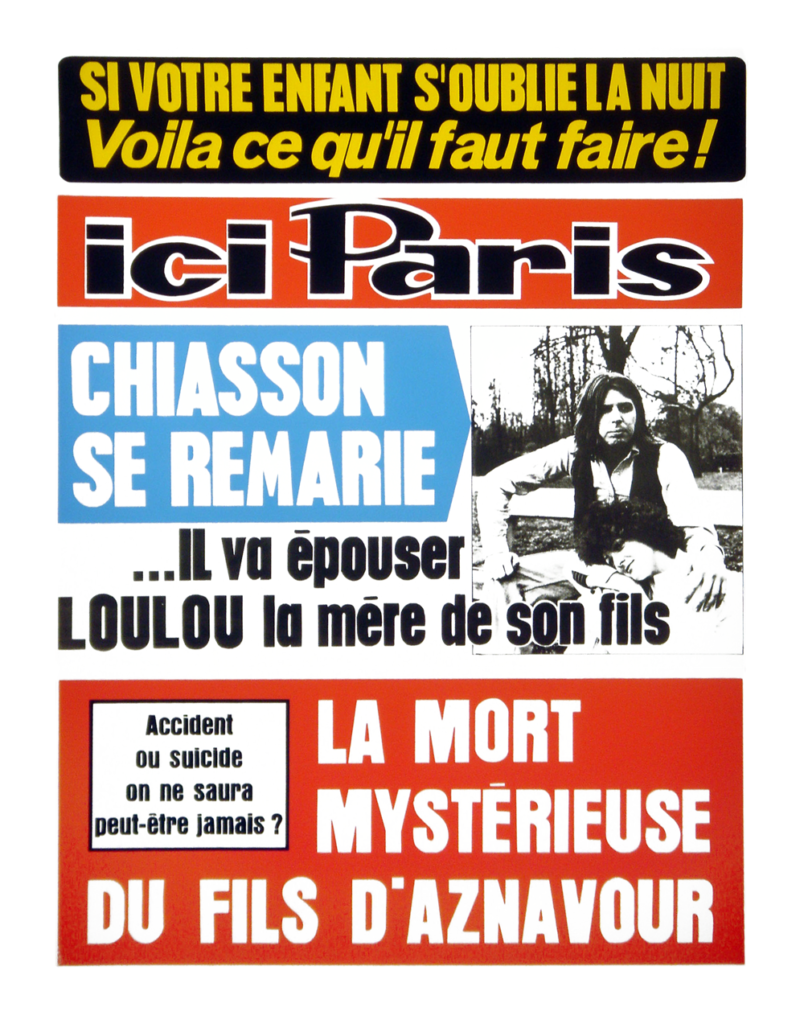

The series of self-portrait parodies that Chiasson created in Paris as part of his master’s degree are among his most conceptual print works, combining elements of mass consumption, art-world reference and autobiography. This eclectic body of faked media included magazine and tabloid covers, postcards from the Tate Gallery, advertisements, commemorative stamps, an imitation Warhol painting and a poster for a retrospective show at MoMA.

These would be the last of Chiasson’s early screenprinting output; he switched over to woodblock printing and other media in the late 70s.

Meanwhile, screen-printing classes at UdeM went going on strong under the direction of Louis Desaulnier, who had become director of the department and was mentoring a young multimedia artist who would find a practical use for the reproductive capabilities of the process.

I Herménégilde Chiasson, Time magazine cover, 1977. Screenprint on paper. Photo: Herménégilde Chiasson.

Herménégilde Chiasson, Time magazine cover, 1977. Screenprint on paper. Photo: Herménégilde Chiasson.

The main drawback with most print techniques is that they require the use of expensive, specialized equipment that can only be found in dedicated print studios.

Because of this logistical challenge, many UdeM graduates in the 70s and early 80s ceased producing prints, opting for more accessible media such as painting and photography.

However, in 1977, painting student and future artist Paul Édouard Bourque found an effective long-term solution to this problem by producing close to 500 screenprints on paper, Masonite, canvas and Plexiglas, generating for himself a bank of images that he would use for years to come.

Of the four images that Bourque screenprinted, three were photographs taken by himself and became respectively known as the Gilles, the Nanettes and the Gaspards. The latter two, similar in their compositions and subject matter, were grouped into one singular body of work that became the artist’s first solo show, presented at La Chambre Blanche in Quebec City in 1978. The fourth image, a publicity shot from the 1976 musical Bugsy Malone, was taken from a magazine and served as the basis for one of the artist’s most recognizable bodies of works—the Mikeys.

These Mikeys, neo-expressionist pop portraits, serve as a prime example of how the artist was working early in his career, perpetually returning to the same stack of images and adding more to the compositions as time went on. Bourque would return to screenprinting only once—in 1984, to produce a series of images called the Cowgirls that, interestingly enough, appear in a handful of Mikeys. These Cowgirl Mikeys or Horse Head Mikeys were the last of the original 1977 batch to be completed before the series switched over to photocopy-based prints. (For further reading on the Mikeys, see the publication produced for “Les Mikeys de Paul Édouard Bourque,” a retrospective show that I curated for the Galerie d’art Louise-et-Reuben-Cohen in 2015.)

By the late 80s, screenprinting was no longer being taught at UdeM, and in the 90s, most of the equipment used for the process was discarded when the Fine Arts Department moved over to a new building.

It would take almost two decades before screenprinting would re-emerge in Acadian art, where it has become central to many contemporary art practices.

Paul Édouard Bourque, Mikey, 1982. Screenprint and mixed media on panel. Photo: Jim Dupuis.

Paul Édouard Bourque, Mikey, 1982. Screenprint and mixed media on panel. Photo: Jim Dupuis.

In the early 2000s, screenprinting made a comeback with the advent of newly developed water-based inks that were easier to work with and less toxic than the industry standard.

At the time, Moncton had already been established as an important printing center through the Atelier d’estampe Imago, a member-based print studio founded in 1986.

However, the studio had never been set up for screenprinting, and the medium had evolved so much since the 1980s that no one in the community could teach it to younger artists.

In 2003, the wheels were set in motion through Imago’s residency exchange program when Acadian artist Jean-Denis Boudreau went to Atelier Graff in Montreal to learn screenprinting and Graff member Dominique Pétrin came to Moncton to share the foundations of the process.

Jacynthe Loranger was the next artist to come and share further knowledge, helping the studio find necessary equipment like scoop coaters, roller frames and squeegees, all purchased in a liquidation sale for $300.

By 2005, a second wave of Acadian screenprinters had emerged at Imago, composed of Jean-Denis Boudreau, Angèle Cormier, Mario Doucette and Jennifer Bélanger.

At that time, paper-based installations and print-based interventions were appearing everywhere in the printmaking world, including in Acadie, where Imago organized a group show on the theme called “Salon de Papier” in 2002.

Jean-Denis Boudreau was among the first artists in the new wave to merge these spatial pre-occupations with screenprinting and other media, creating two distinct bodies of work known as the Spruce-Ups in 2004 and the Instructions in 2005.

The former were screen-printed vinyl stickers that came in little packages, instructing users to stick them on bland framed artworks at home or on family pictures. They serve as a sort of precursor to the more elaborate series of Instructions that were shown together for the first time in a large solo installation at Galerie Sans Nom in 2005.

These later Instructions illustrations, mostly printed on paper and fabric or die-cut in adhesive vinyl, gave viewers step-by-step instructions on how to do mundane tasks: how to sit, how to wash your hands, how to put on a shirt and even how to screenprint.

To this day, a person navigating the artistic community in Moncton might still stumble upon some of these leftover instructions on people’s clothing, on chairs in the Aberdeen Cultural Centre and in people’s home bathrooms.

The Instructions were subsequently shown in solo shows at Third Space in Saint John and Trap Door Gallery in Lethbridge, both in 2007.

Screenprinting would become less central to Boudreau’s work in the projects that followed, save for small instances like 2010’s Funeral Planning for Artists, a colouring and activity book that served as an extension to The Last Show, a mock funeral that artist planned for himself in 2007.

Jean-Denis Boudreau, Instructions, 2005. Installation with screenprinting and die-cut adhesive vinyl. Photo: Mathieu Léger.

Jean-Denis Boudreau, Instructions, 2005. Installation with screenprinting and die-cut adhesive vinyl. Photo: Mathieu Léger.

Artists from the new wave immediately recognized the versatility of screenprinting compared to traditional press-based techniques like waterless lithography, which was a favoured technique at Imago throughout the 90s.

An early project by Angèle Cormier called People I Know and Love serves as a good example; in it, the artist chose to print intimate portraits on Plexiglas rather than on paper. Adapted from a 2004 screenprinted artist publication called Eight People I Know and Love, the Plexiglas works were presented at Galerie 12 in 2005 and featured photographic halftone prints of friends along with textual accounts of their relationship with the artist.

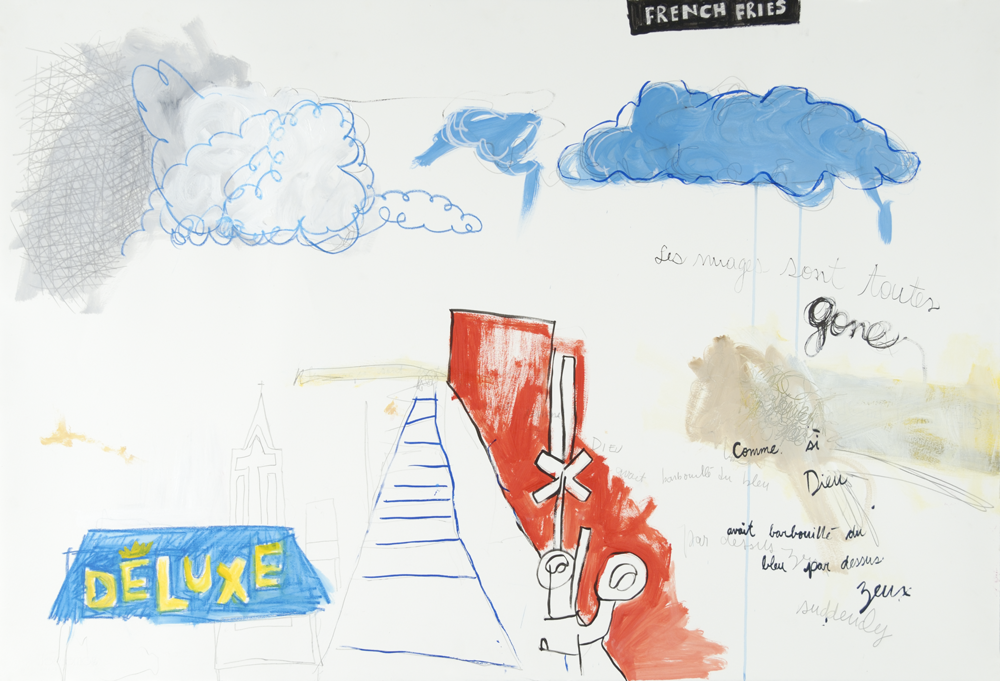

While remaining intimate and autobiographical, this project stands out from the lyrical, and at times abstract, multimedia works on paper and board that Cormier is known for. Merging elements of painting, drawing, typewriter, dry transfer lettering and collage, these other works, informed by the calligraphies of Cy Twombly and Jean-Michel Basquiat, reveal a sort of neo-expressionist poetry that deconstructs the word to its bare aesthetics and transforms the gestural brush stroke into something literary.

Screenprinting would eventually infiltrate Cormier’s multimedia practice, although subtly at first, blending in with other techniques and applications in her 2008 series on the writings of Paul Bossé. Subsequently, her work would undergo a radical transformation in 2012, when she attempted to create one drawing per day for 54 days in the two-person show “Index,” embracing a more minimal approach to composition.

With plenty of neutral space on the page, Cormier’s recent works in 2016’s Les traces du quotidien bring screenprinted elements to the foreground, and they return to the photographic halftone dots that mark her early Plexiglas output.

A 2008 work by Angèle Cormier. Mixed media on paper. Photo: Mathieu Léger.

A 2008 work by Angèle Cormier. Mixed media on paper. Photo: Mathieu Léger.

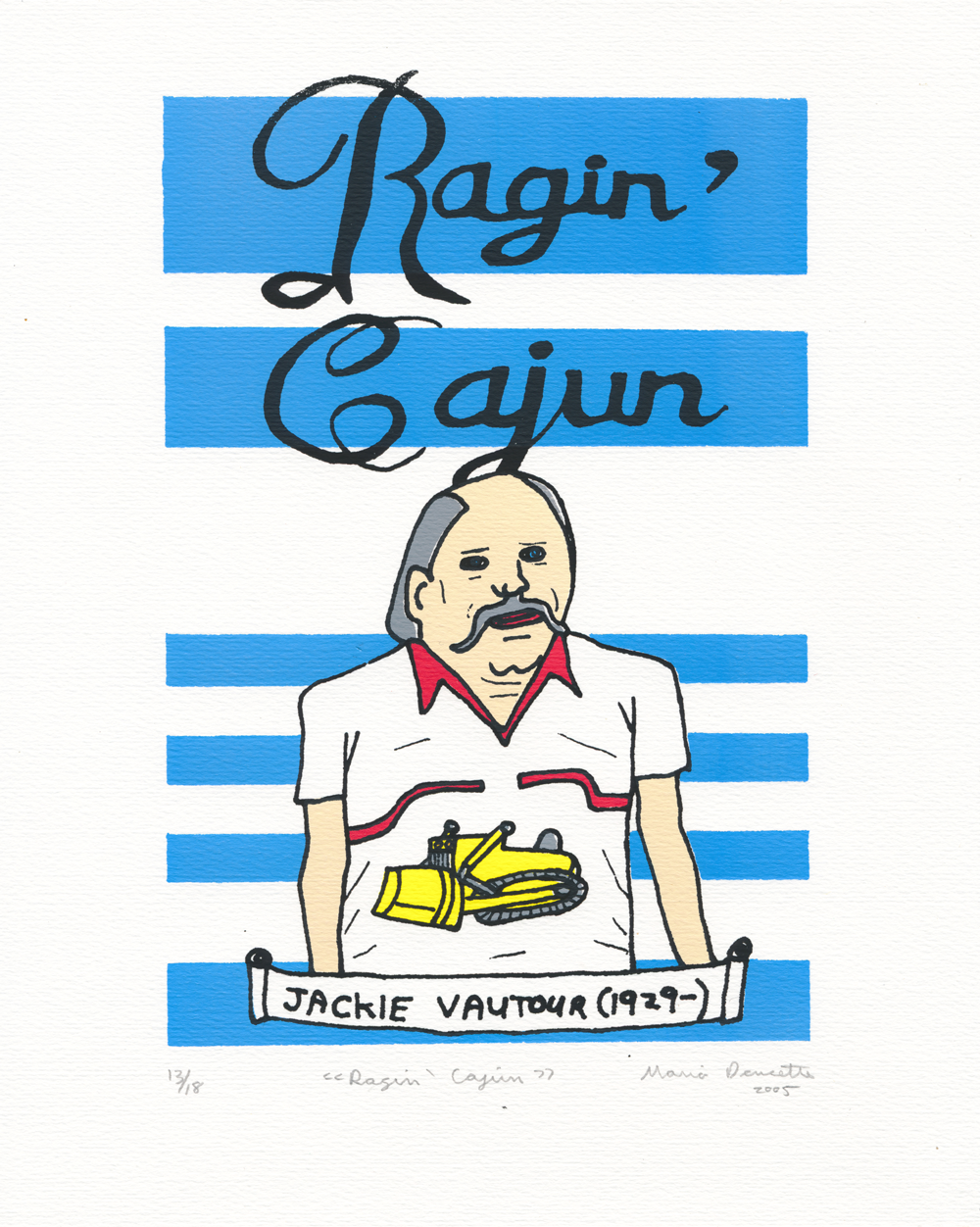

Of the four artists that comprise the second wave, Mario Doucette stands out as one that adopted screenprinting not for its versatility, but for its technical ease of use.

At the time, his comic-book style of drawing and painting lent itself perfectly to the drafting of hand-drawn positives that required less precision when registering multiple colours.

Screenprinting thus became an extension of Doucette’s painting practice in 2005, generating images that differed conceptually from his paintings only in the fact that they existed in multiples rather than in standalone works. At the time, the artist was in the beginning stages of developing his current preoccupation with Acadian history as a falsely reported story of British conquest that had to be revised.

This is where screenprinting’s potential for mass production came to play a political role in the artist’s historical representations, allowing for mass dissemination of what he calls “Acadian propaganda.”

An early attempt at this came in the form of a 2005 screenprinted portfolio titled Les Rebels, coffret no. 1, in which the artist commemorated four rebels, including controversial Acadian figures such as Louis J. Robichaud, Jacky Vautour and Michel-Vital Blanchard.

Later Doucette screenprints like 1755 (la chasse aux anges) and Evangeline (d’après Thomas Faed), both from 2007, push this concept of painter’s propaganda even further by deliberately putting into circulation copies of his own paintings, recreating the print markets that made religious icons out of paintings like The Death of General Wolfe in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Today, Doucette has brought this idea to its logical conclusion, opting for the more historically accurate printing technique of etching in his most recent set of prints, created at Open Studio in Toronto this year.

Mario Doucette, Ragin’ Cajun, 2005. Screenprint on paper. Photo: Rémi Belliveau.

Mario Doucette, Ragin’ Cajun, 2005. Screenprint on paper. Photo: Rémi Belliveau.

By the late 2000s, Acadian artists like Mathieu Léger and the now defunct Taupe Collective had begun moving outside of the gallery and into public space with performance and intervention works that relied largely on chance observers.

Jennifer Bélanger was among them, with print-based interventions like her 2008 weed decoration project—where she embellished unsightly weeds with edible screen-printed communion wafers—or her 2009 master’s project where she hid hand-pulled paper dollhouses inscribed with the words “finders keepers” in the hollow spaces of trees.

The thrift store also became a sort of public playground for Bélanger, who had already been altering and printing on second-hand objects when she began work on her solo installation Song and Dance, presented at Galerie Sans Nom in 2011.

This furnished cube space, complete with wood-panel walls and carpet flooring, was decorated with 80s offset portraits onto which the artists had screenprinted captions such as “Her parents lied to her by telling her she could be anything she wanted to be.” We see in this work the artist’s ongoing preoccupation with intimate storytelling through the misappropriation of found objects.

Bélanger’s interest in found objects is further explored in another screenprinting project where she used expensive Japanese paper to recreate napkins, salt packets and moist toilettes from the Dixie Lee chain of fast-food restaurants—an Acadian classic that she associates with family trips to her aunt’s house.

Many of Bélanger’s works claim an autobiographical voice that offers viewers insight on her experiences and intimate thoughts. Her 2013 project Love Jennifer gathers 10 personalized fan letters written to 10 lifelong celebrity crushes, each represented by a screenprinted wooden taxidermy plaque. Viewers are invited to pick up the objects and read the love letters on the back, leaving them to sort out the playful fandom from more personal statements like “we could speak French together.”

The evident plurality of Bélanger’s screenprinting practice would prove useful to an emerging generation of artists in 2009, when she became the first instructor to teach the process at UdeM in more than 20 years.

Jennifer Bélanger, Dixie Lee, 2010. Screenprint on Japanese paper. Photo: Rémi Belliveau.

Jennifer Bélanger, Dixie Lee, 2010. Screenprint on Japanese paper. Photo: Rémi Belliveau.

Alisa Arsenault and myself were among the first to study this new school, forming a sort of post-wave of Acadian screenprinters interested in merging screenprinting with elements of video, sound design, artifact-based installation and performance.

Arsenault, especially, has consistently made good use of this interdisciplinary approach in exploring notions of personal mythology through her family’s archives.

Her 2012 installation John Doe, composed of artifacts, screenprinted photographs and an audio track, is an investigation into the life of her enigmatic great-aunt Lina based on personal effects that she left behind after her death.

Among them: a love letter, written to her by a soldier named John D. during World War II, which the artist captured through the voices of 10 men close to her, and edited down to one single reading. The resulting audio recording renders the voice of the love letter current and ambiguous, making it unclear whether or not the letter is addressed to the aunt or the artist.

In this way, Arsenault appropriates the memories of family members, performing them to see how they might have indirectly impacted her present-day self.

In The Dumps: Always and for Never, shown for the first time at Struts Gallery in 2013, the artist wore screen-printed masks representing two of her mother’s ex-boyfriends, and she performed their imminent breaks-ups on video.

Arsenault’s follow-up project, Préserver quʼune seule mèche de cheveux (…),digs deeper into her own childhood memories using her family’s Hi8 home movies as material for interrogation.

This time, Arsenault replicates the clothing worn by her and her brother over Christmas one year, wearing the screenprinted cut-outs in the manner of a paper doll. Photo-documentation of this gesture was shown alongside the printed clothing, looking over a set of centred plinths that contained locks of her and her brother’s hair encased in Plexiglas.

Coupled with a looping television set and large wall projection, the Préserver quʼune seule mèche de cheveux installation communicates much like an interactive museum exhibit, highlighting the artist’s preoccupation with the notion of preservation, or in this case, conservation.

Alisa Arsenault, The Dumps: Always and for Never, 2013. Video still.

Alisa Arsenault, The Dumps: Always and for Never, 2013. Video still.

The latter project is a prime example of the high-calibre contemporary explorations that Imago fosters in emerging printmakers through its Bourse Imago annual grant program, Arsenault having been the 2013 recipient.

Offering access to equipment, materials and mentorship, as well as a solo show at Galerie Sans Nom and a professional artist fee, the Bourse Imago guarantees a steady succession of engaged print artists that, in the last seven years, have all been screenprinters save for one.

What makes this particular process so popular with artists here?

Maybe it’s the fact that Acadian art, having been generated in the cultural isolation of the francophone Maritimes, has always relied on relatively few means to make meaningful statements—and that, to the contemporary printmaker, screenprinting is a medium of relatively few means, relying not on presses, metal plates, bites or stones, but on light which is readily available to anyone, anywhere.

Is Moncton really a screenprinting city? Possibly, yes; and certainly, it is, and will remain, at least in the foreseeable future, a place where contemporary Acadian culture happens.

Rémi Belliveau is a Moncton-based multidisciplinary Acadian artist working primarily in screen-printing and installation. Using archival images and objects as base material, his practice attempts to define a visual nomenclature for describing the mechanisms of Acadian culture. He currently codirects Galerie Sans Nom.

This article is part of Canadian Art’s year-long Spotlight on New Brunswick series, created with the support of the Sheila Hugh Mackay Foundation.

Herménégilde Chiasson, Ici-Paris, 1977. Screenprint on paper. Photo: Herménégilde Chiasson.

Herménégilde Chiasson, Ici-Paris, 1977. Screenprint on paper. Photo: Herménégilde Chiasson.