I walk into your bathroom and sitting in front of the toilet is a shelf full of pastel-coloured crystals. I don’t know the names of them but I know crystals form as magma cools, slowly. Somehow these rocks have a special meaning to you, and I guess a lot of other people, but I assume they’re just decoration. I remember how mad this white girl got once when I touched her piece of amethyst; in her defence, I didn’t ask permission. I wondered whose grandma you asked permission from to get sanskrit tattooed on the back of your neck. It’s not until I turn around to flush the toilet that I see the braid of sweetgrass laying on the toilet tank. I can tell by the uniform cut and neat string holding the braid together that this is store-bought. A note beside the braid reads: “light me up after you take a dump.” I start laughing because if this scene isn’t an allegory for colonization, I don’t know what is.

i wonder if you know that

this braid is kokum’s hair

i wonder if you know

what it feels like

to run through a field

of sweetgrass.

when i moved to the city kokum gave me a braid.

it sits in my room, by my bed, holding me.

It’s easy to laugh at all these moniyawak thinkin’ they’re something spiritual: always on a quest to find themselves by sifting through piles of colonial souvenirs. To the left is a stick of Nag Champa incense burning on your desk, next to a selection of books about yoga. On your windowsill, there are three veladoras de Virgen de Guadalupe. Your blonde hair is tied up messily in a bun with one piece rolled into a white version of a dreadlock, the frizzy and frayed tip decorated proudly with carved wooden beads. Above your bed a dream catcher hangs. It’s not a surprising scene for anyone who has lived under colonization—to see things from my people spread carelessly throughout your white, witchy, queer house.

i tell you i have a cold

you ask me if i have ever heard of rat root

i say that it’s kokum’s cure-all

you don’t hear me and say it’s a weed

that grows in a swamp

but it’s good if you got a cold.

You lay your head back and let your hair tangle in the sand. We watch the clouds float over the mountains; the air is peppered with salt and seaweed. I pick up discarded shells and examine their outsides: rough, purple and jagged. You are telling me that you are gonna go up the mountain to be on the front lines. I watch you throw your blonde hair over your shoulder. You’re gonna go up there and protect the land. I stop listening because there are few things more annoying than moniyawak telling you they’re going to “protect the land.” I watch the tide slowly come in, salt water licking the shoreline. I tune back in and hear the words “warrior up” leave your mouth. I tune back out and watch seagulls land and take off from a rock. “We women” you say, “we women are the land.” I laugh and you’re mad I’m laughing. You tell me that I never stand up for anything, that you’re the one who’s willing to get arrested for the land.

i’ve been standing in footprints

left here by the old ones before me

i’ve been standing in them since

i was protected in the womb.

I saw on your instagram that you got arrested “for the land.” In the back of the cop car you and two other moniyaw iskwewak take a selfie. Your caption reads something about being land defenders. I wonder if any one of the 150 likes would have told you that the reyes filter doesn’t hide your privilege. I wonder if any of the comments by classmates in your “Ethnography in Circumpolar North” class would tell you that you get to take a picture in the back of a cop car because you’re a frail-looking white girl. That in the circumpolar north, when native men with brown skin get in a cop car, there’s no instagram filter to hide stories of starlight tours of wrongful arrests; of brutality; of this long history we have with the rcmp, but hey, warrior up, right?

I see you a couple weeks after your “arrest.” You’ve changed, I can tell the attention you got from your cop-car photo op has gone to your head. You’re wearing a t-shirt with the unity flag on it. You have a stick ’n’ poke running down your finger that reads “decolonize.” Blonde hair dyed brown with a braid that falls to your shoulders. Your braid isn’t tight enough and your hair is too fine to use grease, so the look you’re going for isn’t complete. Frizzy ends stick out. You tell me that you’re a firekeeper now and I have to look intently at the ground to keep from laughing. You say that you’re going to get your indigenous name soon. I ask you which nation from this land is gifting you a name? And you say the name of some guy with a name like white wolf big bear from montana is giving you a name. You met him on the warrior trail, you say. You say that for $200 white wolf big bear will take you to a sweat, and for an extra $100 you’ll get a name. On your bag, there’s a patch that says “remember Oka.”

we remember the struggles of the ones

who came before us

their fights are passed down

in our blood.

I finish my beer and order another. I ask if you’d like one and you say that you’re on a cleanse before your $300 ceremony. You tell me, in between drags of an american spirit, that you’ve never felt more pure, that next month you’re gonna go foraging for medicines. You’re going to make tinctures, salves, smudge. You ask me if I wanna come. My mouth says, “yeah, sure, let me check my schedule.” But my brain is saying, “Who are you to take from this land? Who am I to take from this land? My schedule is now full.”

The absurdity of well-meaning white activists wanting to collect medicines bothers me right through to my third beer. I’m silent as you talk about your next front line. Filled with happy-hour courage, I finally say, “Why

do you think it’s okay that you collect medicines from this land?” And you say that the earth is here to provide for us, that her medicines are for the people. That we all can benefit from her gifts. I tear the first layer of paper off my coaster.

“But why do you think that you have a right to take from this territory, do you have permission?”

“Sam, this land is here to provide. I don’t need permission to take from the earth.”

remember oka.

“Yeah but you’re a settler on this land and that comes with responsibilities. Like I’m an uninvited visitor here and I would never gather med’cines from these territories without permission.”

“I don’t need permission to take what the earth has provided for free.”

remember gustafsen lake.

I tear the second layer of paper off of my coaster. I can hear the blood rushing through my veins, heart pounding.

“Also, Sam, the term ‘settler’ is so polarizing and really I’ve been doing more work on this land than a lot of Aboriginal—sorry—Indigenous peoples here. I don’t feel like I’m a settler anymore.”

“Aren’t your parents like fifth generation English?” I rip the third and final layer of paper off my coaster. I stack all three layers on top of each other.

“I am not my parents. I have decided to dedicate my life to defending this land. Plus, I’m doing so much more than a lot of people who never do anything but complain on the internet and never hold the front line. I was told to warrior up, so I did. What are you doing to defend this land?”

remember idle no more.

Fourth beer down, I tell you you’re right. You’re doing more than me. I tear the final piece of coaster into confetti. I ask the server for my bill, pay and walk outside. You offer me one of your american spirits, but I decline. Instead I walk up to a group of white men and bum one of their pall malls. I light the cigarette and start to wonder how you afford to not work, go to university, and “be on the land.” This reminds me that I have to call Tanis, the lady in charge of school funding for my nation. They didn’t pay my last tuition instalment and the school is threatening to not let me graduate.

“Why don’t you ever fight, Sam?”

inhale/exhale.

“You know I see a lot of other halfbre—Métis up there.”

inhale.

“You’re not honouring your ancestors if you’re not defending the land, you know, like I’m honouring mine doing this work.”

exhale.

“Like you know Sam, there’s no such thing as a free lunch.”

hold your breath.

All I say is “yup” and flag a cab and leave. Shaking from anger and laughing at the same time. The audacity.

i close my eyes and remember what it feels like

to feel the glacier waters of moberly lake

hold my body—so cold it makes breathing hard.

i close my eyes and remember what it’s like to run my hands over

paper birchbark. run my hands over braintanned hide.

to taste kokum’s baked bannock with margarine.

to taste fresh elk meat.

to find a hummingbird’s nest at grandma’s-on-the-farm.

to walk with grandpa through the bush, in silence.

only pausing to point out where a moose

had rubbed the velvet off his antlers.

i close my eyes and remember ski-doo rides and the trapline.

camping along the sukunka, spending my days

exploring the woods with no fear.

finding fossils of seashells and lizards in northern bc.

not understanding that

this land has its own history.

this land has fought hard to keep itself alive.

kokum says that everything she does is for the youth.

16 years as our local’s president, she worked hard for our future.

front lines. defending our people. making sure we know who we are.

is this front-line work?

The cab pulls in front of my house. I pay and get out. Looking at the sky, the stars are hidden behind light pollution. Sometimes I get nervous when I can’t see the north star. Dad said that’s the one I follow home if I’m ever lost. I can’t see the north star tonight. The air is heavy and muggy. The leaves are pointing down. It’s going to be raining by morning.

Her words echo through my body, “what do I do? what do I fight for?”

My dad teases me that my first words were, “what’s that?” Always questioning before I knew how to run. When I was little, I was able to describe houses I never lived in. The ones my mom grew up in. I was able to describe places in île-á-la-crosse to kokum, without ever being there.

sometimes i feel like

my fight is remembering

my fight is surviving

so that the next generation

doesn’t have to only

remember

and

survive.

I don’t see her again for months. The next time I do I see she has an article published in an activist newspaper. In her bio, she says she is “Métis” from “Northern Alberta.” I start laughing—I can guarantee you she has never walked on northern alberta snow. Next to her birth name is the name she paid for. Her words are there to appeal to other white activists. Hold them. Coddle them. Call them in.

She ends her piece with:

If we don’t fight, who will?

let the water of the kiskatinaw flow over your hands

walk down her shores

let her currents wash over your body

remember iskwesis

you are more

than politics

you are more

than activists

our fights are where we follow our ancestors

our fights are making sure we survive.

There are so many things that well-meaning moniyawak steal without realizing they’re stealing. Co-opting our fights, our languages—not realizing that we all have to tread carefully, with respect, on these lands.

lay your head down in northern prairie grass

dig your fingers into the dirt

listen to the wind through poplar trees

know that this is something

they can’t take from you

let the land hold you

and wrap herself around your body.

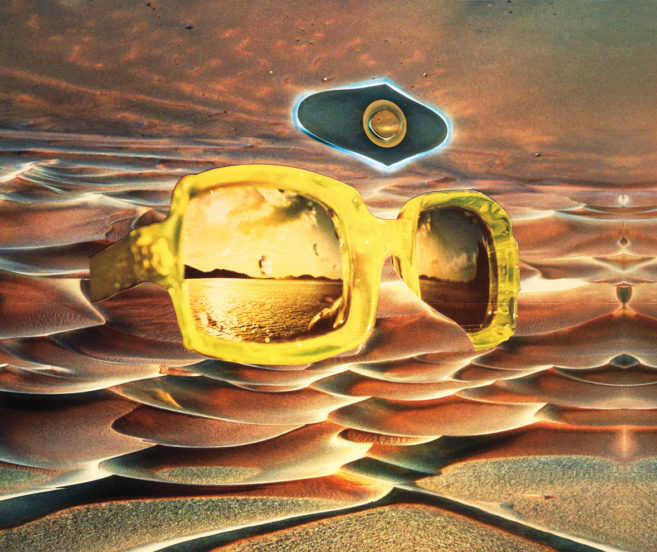

Maggie Groat, Of Another Natural History II, 2011. Collage, 83.8 x 63.5 cm. Courtesy the artist. Collection TD Bank.

Maggie Groat, Of Another Natural History II, 2011. Collage, 83.8 x 63.5 cm. Courtesy the artist. Collection TD Bank.