“There used to be only two albums I could listen to when I was painting,” Rudi Aker tells me. When I ask her which two, she pulls out the Where The Wild Things Are soundtrack (2009), and Sufjan Stevens’s Seven Swans (2004). “I like albums that are good for crying and for dancing. Both things at the same time,” she describes.

When we first met, Rudi was studying visual art at Concordia, but now she’s taking some semesters off from school. “Institutional death—that’s what that felt like. I just wanted to peel my skin off,” she says. “I kept trying to make it work for me, but it was like when your car runs out of gas and you just keep turning the key in the ignition, hoping that something will happen…” She pulls out a Weakerthans album, and tells me, “when I was living in Montréal, I used to listen to ‘Left and Leaving’ on repeat when I was feeling homesick, and I would just cry and cry and cry…” She pauses. “Really, they’re like the Canadian Death Cab (For Cutie),” she says, and she laughs.

For now, she’s moved back to Fredericton, New Brunswick—the city where I’ve made my home since finishing my BFA in Vancouver. This is where Rudi grew up, spending her formative teenage years living with her maternal grandparents at St. Mary’s (Sitansisk) Maliseet Reserve on Fredericton’s North side.

There are other albums she’ll paint to now too: she holds up The Velvet Underground & Nico (1967), Bright Eyes’ I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning (2005), and Chastity Belt’s No Regerts (2013). Chastity Belt’s an all-girl band out of Washington, with songs like “Healthy Punk”, “Giant (Vagina)”, and “Pussy Weed Beer.” There’s a troubled, confessional quality to Rudi’s paintings that is definitely echoed in their music, and it makes me think of other projects like Old and Weird, and Glitterclit, and of Walter Scott’s Wendy comics too:

I can’t see straight

The room is spinning

I just wanna have a good time

(Chastity Belt, “Time To Go Home”)

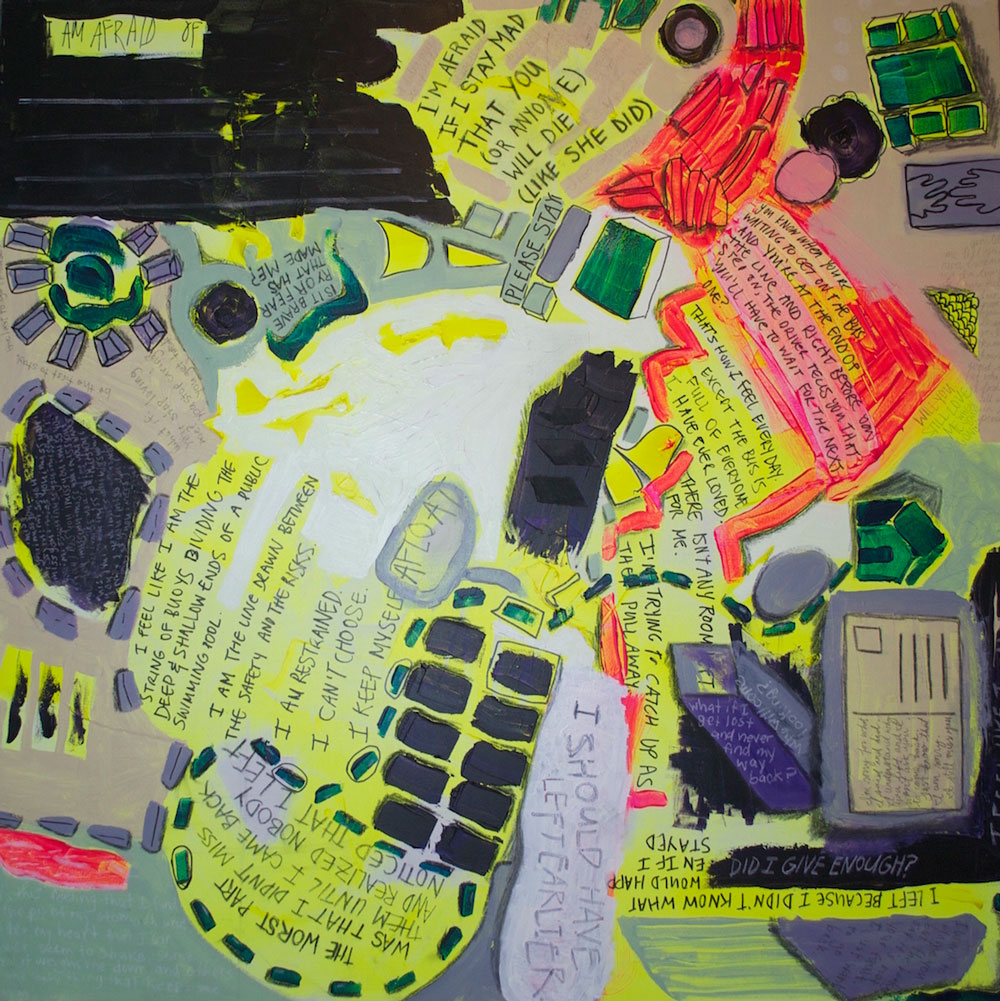

Rudi Aker, it’s too busy, 2015. Courtesy the artist.

Rudi Aker, it’s too busy, 2015. Courtesy the artist.

“A lot of it comes from a kind of aggression. Like I’ve got this overwhelming need to act, to do something in the world.” Used to be that she would engage in all kinds of self-destructive behaviour when she felt this way, she says, “Now I paint, I use it all to paint.”

I describe her paintings as frenetic and crowded, awkward and painfully honest, and she tells me that these dense pictures are very much about exposing the parts of herself she’s kept carefully hidden—including her Maliseet heritage, and the intense way she experiences the world, as someone who is rapid-cycling bipolar. “These days, I’m really preoccupied with being sincere,” Rudi says.

She asserts that for a lot of her life she lied to herself, not only about how she was, but about who she was. “And then for awhile I was buying in to this whole Winona Ryder Girl, Interrupted thing, where I thought my sadness was beautiful and poetic, and that I had to stay in that place in order to make art.” Rudi shakes her head. “But that’s a really hard way to live, and it’s not something I benefited from at all.”

We talk about using art as a tool for living, and about wielding art as a weapon. She quotes a Bikini Kill song, “Bloody Ice Cream,” when she describes her art practice as a way to point a knife towards colonial, patriarchal power:

The Sylvia Plath story is told to girls who write

They want us to think that to be a girl poet means you have to die

Who is it that told me all girls who write must suicide?

I’ve another good one for you, we are turning cursive letters into knives

(Bikini Kill, “Bloody Ice Cream”)

Rudi Aker, sourpuss, 2015. Courtesy the artist.

Rudi Aker, sourpuss, 2015. Courtesy the artist.

When she’s painting, Rudi moves quickly. It doesn’t usually come all at once, but it comes in hurried spurts. “When I first started painting, I painted with oils. It was like being seduced! Everything’s so smooth and buttery…” she relates. “But as I got more impatient, I switched to painting with acrylics,” she says.

Speed is important. She always keeps her paintings moving, turning them constantly while she’s working, so that none of them have a definite orientation: any one of the four sides can be “up” or “down.” Her canvases are full of words and black lines and synthetic colours: layers and layers of paint built up in the graphic style of a teenage diary, or like bathroom-stall graffiti.

This way of working anchors her practice, but then, Rudi’s always telling me stories about her Nana—her grandmother—who taught her how to knit and to sew and to crochet. She’s hoping that over the winter her Nana’ll teach her about weaving, though she’s still trying to figure out how all of these craft practices exist in relation to her paintings.

The elusive concept of “love” is another kind of anchor, at least for the moment. Rudi’s been reading Raymond Carver’s short stories, What We Talk About When We Talk About Love (1981), and bell hooks’s treatise All About Love: New Visions (2000). She’s also started reading Miranda July’s No one belongs here more than you (2005), and she says about July, “I feel like she knows something about love.” And there’s Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, where she talks about falling in love with colours. “That totally happens to me,” Rudi says. “I’m still really stuck on yellow…”

When I asked her why she took up the idea of love in her readings, she said, “Oh I don’t know.” And then in a funny voice, parodying herself, she said, “I don’t understand this thing, so I’m gonna do an art project about it.”

A view of Rudi Aker’s apartment and studio in Fredericton. The artist recently returned from training in Montreal.

A view of Rudi Aker’s apartment and studio in Fredericton. The artist recently returned from training in Montreal.

Rudi’s paintings are found throughout her apartment, but so are her houseplants and her books, her music and her knitting, and all the macramé plant holders she’s made. She and I agree that artworks always develop inside of complex ecosystems, contingent on other forms of looking and listening and making: every thing being dependent on other bodies in the world.

We talk about magic, and the way she had learned to dismiss her Nana’s stories and medicines through public school socialization, particularly as a teenager. “What have I let be taken away from me?” Rudi asks. “What have I taken away from myself?”

Rudi Aker, it’s too little, 2015. Courtesy the artist.

Rudi Aker, it’s too little, 2015. Courtesy the artist.

She poses these questions explicitly at the surface of her painting it’s too little (2015). In one corner of the painting there’s a medicine wheel, and when I ask her about it she explains that she only put it in there because she got pissed off when someone told her that her painting “wasn’t Native enough.”

Our meandering conversations—first about the idea of love, and now about The Neo-Liberal Colonial-Industrial Complex—remind me of some of the ones I’ve had with Adam Sturgeon, an Anishinaabe musician whose band WHOOP-Szo did a month-long residency in Fredericton for Flourish Festival this past April:

The traditional life hasn’t found me yet

Like you do

WHITE TRUTH

(WHOOP-Szo, “Odemin”)

Rudi’s hands are fidgeting with a paintbrush and some scraps of paper on her desk, as she slowly considers another thought, saying, “you know, back in the day, time used to be told by the moon. The passing of time used to based in the cycles of nature…” she pauses, “In terms of capitalism, there’s always some newer, better way to do things, but like, what if we still told time by the moon?” her eyes twinkle. “Couldn’t we still do that?”

sophia bartholomew is an artist based in New Brunswick who works with performance, language, and other time-based media. She co-directed Connexion Artist-Run Centre in Fredericton from 2012 to 2015 after finishing her BFA at UBC.

This article is part of Canadian Art’s year-long Spotlight on New Brunswick series, created with the support of the Sheila Hugh Mackay Foundation.

Rudi Aker in her Fredericton studio. The Maliseet artist was raised on a reserve on the city’s north side, and her frenetic paintings “point a knife towards colonial, patriarchal power,” writes sophia bartholomew. Photo: Courtesy the artist.

Rudi Aker in her Fredericton studio. The Maliseet artist was raised on a reserve on the city’s north side, and her frenetic paintings “point a knife towards colonial, patriarchal power,” writes sophia bartholomew. Photo: Courtesy the artist.