From September 2013 to May 2014, I had the fortune of devoting a small parcel of my week to Canadian Art as the magazine’s editorial intern. During this time, though my own interests as a critic often anchored me steadfastly in the present, I found myself immersed at various times in Maritime high realism, London Regionalism and Canadian Art’s own history and archive. Earlier in the year, in the pursuit of two 1950s covers designed by Arnaud Maggs for a different and preceding publication also called Canadian Art, I happened across a questionnaire in an April 1966 issue on the role of the art critic.

Part readership survey and part serious interrogation of criticism’s influence (or lack thereof?) in Canada at that moment, the survey (reproduced here) struck me as containing questions that were still incredibly pressing. As an emerging critic, I find myself often preoccupied with whom I am writing for, and what should be done to ensure I am writing with both deep honesty (even, perhaps, with intuition) and strong reasoning. Unearthing the 1966 survey, I hoped, too, that artists, critics, curators and dealers across Canada might share some of my preoccupations, and find the survey questions (and their answers) as fascinating and frustrating as I did. As my internship drew to a close, I put 10 of the original survey questions to arts workers across Canada by email. Here are their selected responses.

1. Do you think that art criticism can be useful? If yes, to whom especially?

Clint Neufeld (artist, Osler, Saskatchewan): “Sometimes, for some people. I only like criticism when it is useful for me, I don’t really like the word criticism because it implies something negative; I only like it when it’s positive or when someone can point out something in my work that I may not have seen before. Rarely do I read critical reviews on other people’s work. Ultimately I’m not sure who the intended audience is for these things, which is OK because I don’t have an intended audience for my work. I just do it and hope that things fall into place.”

Mary MacDonald (artist, curator and director of Eastern Edge Gallery, St. John’s, Newfoundland): “Yes. I believe art criticism can be useful to all students of art including artists, curators, historians, writers, directors, funders, the whole gamut! Good criticism is informative and expansive without limiting the reader’s own imagination. Good criticism can also expand how we experience an artwork and offer insight of its value as it relates to the broader field.”

2. What should art criticism contain?

Caoimhe Morgan-Feir (critic and editor of KAPSULA, Toronto, Ontario): “Above all, it should contain a sense of time and space. It’s easy enough to find basic information about a work of art; I read art criticism to learn about someone’s singular experience with it. Tell me how the temperature altered it, or what the light brought out. Ultimately, art criticism should be, by equal measures, grounding (context, history, etc.) and transporting.

And, of course, judgment— it’s perfunctory, but necessary. It should always be present, even if the final verdict is ambivalence. A review without judgment is just a press release.

Finally, a beautiful sentence never hurt.”

Peter Dykhuis (artist and director/curator of Dalhousie Art Gallery, Halifax, Nova Scotia):

“- brief discussion of the conceptual structure of the work and descriptions of its physical construction/presence

– an overview of the artwork’s exhibition/presentation values

– critically positioned analysis of the above”

Mark Igloliorte (artist, Sackville, Nova Scotia): “Passion and voice. The critics that I can’t get enough of have both. Fairfield Porter, Ryan Rice, David Hickey, Sherry Farrell Racette and Peter Schjeldahl to name a few.”

3. What do you feel is the role of the art critic today?

Gina Badger (artist and editorial director of FUSE Magazine, Toronto, Ontario): “I believe that art, no matter the form, is first and foremost a social process. In light of this, the role of the critic is to attentively and generously take artists and the presenters of their work (galleries/museums/artist-run spaces/etc.) to task for how the work comes to life. Does the artwork live up to the role carved out for it? Does it exceed it? Fall short? Evade it entirely? What are the consequences?”

Daniel Wong (artist and co-member of the Cedar Tavern Singers, Lethbridge, Alberta): “ I don’t think that I read enough art criticism these days to be able to give a valid answer. But maybe the lack of necessity I feel towards reading art criticism is my answer.”

Mary-Anne McTrowe (artist and co-member of the Cedar Tavern Singers, Lethbridge, Alberta): “We still have art critics? Ha ha, just kidding. Perhaps the critic is there to validate the artist’s work. I don’t mean that in a cynical way, but that the critic is there to (attempt to) contextualize the work within the world and within broader contemporary art trends in ways artists may not be able, or interested, to do.”

4. In your opinion, what constitutes the minimum training, academic or otherwise, and experience in the visual arts that would equip a critic to fulfill his role?

Luis Jacob (artist, critic and curator, Toronto, Ontario): “If education is the process of inculcation in dominant values, then criticality, understood as the assertion of challenging values, is fundamentally something that cannot be taught. Having said this, I recognize the importance of higher learning and scholarship—if for no other reason than to provide a clear sense of what critical practice would resist and what it would advocate for. Culture is essentially a field of conflict, an arena where different systems of value compete for legitimacy over one another. Critics must learn to use as many of the tools at their disposal in order to challenge the ways we all participate in this struggle over legitimacy.”

Peter Dykhuis:

“- experience in any (minimum) combination of two of the four following practices/vocations:

– past/current studio practice

– past/current art historical studies

– past/current curatorial studies

– past/current journalism experience”

Mark Igloliorte: “I believe that artists and critics benefit from academic training. At the same time, when I think of the drawings of Annie Pootoogook, who learned from her mother and grandmother, I believe there could also be an art critic whose training is also not academic. Yet whose writing is as absorbing and developed as Pootoogook’s artwork.”

5. Who should art criticism be directed to reach? Why?

Amy Fung (critic and curator, Vancouver, British Columbia): “Back in 2011, I organized an event in the UK inviting a small group of critics, curators, and artists to kick around this silly question: ‘Who Are We Writing For?’ It was a gut check on the state of art writing including artist statements, curatorial essays and reviews, all of which felt and continue to feel oversaturated with the need to be canonized before the need to be read. I still don’t know who I am writing for, but I am writing for readers who care about language, because first and foremost, art criticism is communication before it is opinion.”

6. Do you feel that sound critical reviews (good or bad) have an influence on artists’ work and its direction?

Jessica Bradley (curator and director of Jessica Bradley Gallery, Toronto, Ontario): “Artists do what they do. If they are any good, they will follow their path steadfastly, which does not mean they are immune to constructive criticism. Some of course will be more open than others to comments that may assist them in understanding why a viewer, including informed ones, might not ‘get’ what they believe to be inherent in the work, but this rarely leads a good artist to changing the direction of their work, just maybe going deeper, refining their intent and vision.”

Clint Neufeld: “I don’t think that I can speak for all artists. It may happen. I think that artists do work for themselves, at least I do. So the input of a stranger, if it is bad, tends to be ignored. But if good, it may have a tendency to reinforce the direction that the work or practice is going.”

Caoimhe Morgan-Feir: “They may do, but that’s entirely at the artist’s discretion. An exhibition review should never masquerade as an instruction manual.”

7. Whether incompetent criticism praises or condemns, do you believe that un-sound critical reviews ultimately damage an artist with his public? If so, why?

R.M. Vaughan (critic, video artist and writer, Toronto, Ontario, and Berlin, Germany): “No, nobody has that kind of power anymore, as a ‘critic’ (a word I dislike intensely, by the way). The bad old days of critics ruining people’s careers are long over, and the arts media as it was once understood is dead, so nobody can make you an art star anymore either.”

8. Whom do you consider to be a competent critic(s) of contemporary art, writing anywhere in the world today? For what publication or other media does he/she write?

R.M. Vaughan: “Anybody who makes me laugh and/or want to see an art show.”

Gina Badger: “Anyone who has the capacity to offer an informed and nuanced perspective on the artwork/exhibition/program in question, no matter their background or training.”

Mary MacDonald: “I’m very fond of Cabinet Magazine and its critics for an international publication. I look to Mike Landry in New Brunswick, for example, as well. He writes with such clarity and thoughtfulness that strikes just the right balance between an informed speaker and general reader. But he also has a very supportive editor, and I believe the lack of supportive editors is the reason why we don’t see art criticism in more popular venues. Stereotypes of contemporary art as being elitist and perhaps not for everyone still pervade popular culture. I also admire Sky Goodden who writes for Blouin Artinfo Canada in her no-nonsense approach.”

9. It has been said that art criticism in Canada is too kind and generous in the effort to encourage and promote the arts in this country. Do you think that is true?

Luis Jacob: “Most of what passes for art criticism is simply publicity. What this shows is an absence of autonomy prevalent in the art world, which affects artists as much as writers. If their contributions are to count as criticism at all, art critics are those writers who are capable of creating a practice that is not identical to publicity, in the sense of asserting through their writing values other than the prevailing ones. It is conceivable that the kind of art critique I am suggesting might require generosity—attunement— towards art practices that are themselves critical of prevailing cultural norms.”

Amy Fung: “I’m not confident that there is a culture of art criticism in Canada that acknowledges the labour of the writer. For all of Canada’s accomplishments in establishing minimum fee schedules for artists, writers are not a part of that equation. It takes a lot of energy and knowledge and time to write and respond to art, and when this labour is made invisible, writers stop writing and instead we end up with this advertorial fluff that dominates for what passes as art criticism in this country.”

10. Is there any validity to such a concept as “Canadian” art?—or “British” art, “French” art, “German” art, etc.

Daniel Wong: “With our evolving understanding of connectivity, borders seem less prevalent. Maybe those labels are still important for bureaucrats, but how do you even define something like ‘Canadian Art’ these days? Any attempt to do so will also reveal exceptions. Is it art made in Canada? What about Canadians who have been living abroad for the past 10 years? Is it art that has uniquely Canadian content or style? How can you determine that when so many are influenced globally and trading ideas through things like the Internet? What about immigrants who bring experiences from another country and make work about that? Does their work become Canadian when they receive Canadian citizenship?”

Mary-Anne McTrowe: “In contemporary practice, artists are exposed on a regular basis to international ideas and trends and with the cross-pollination that is always taking place. Those terms don’t really seem to be useful anymore, unless perhaps you are applying for a grant. Like Dan said, as you try to come up with a definition you risk just descending into semantics.”

Jessica Bradley: “In reality a monolithic identity is neither possible nor desirable. Concepts such as Canadian art [or] German art are spurious, impossible to define. Even though we may be able to come up with a few characteristics, there will always be other cases that dispel the categories and characteristics. To pigeonhole contemporary art into national stereotypes is, to say the least, restrictive and a misrepresentation. Of course we make and receive art from a specific cultural position, consciously or unconsciously. National and cultural experience will inevitably determine an artist’s concerns, content and material expression differently in Portugal, Norway or Cuba—obviously. And globalism doesn’t mean lack of definable differences—fortunately, not yet anyway. But today we are all exposed to wider horizons than nationality, both inside and outside the art world, and these multiple perspectives merit being reflected in our definitions of art.”

Alison Cooley is an emerging critic and curator based in Toronto. To read the original 1960s survey on which this 2014 article was based—and answers from that earlier time by Joyce Wieland, Guido Molinari, Christopher Pratt and others—visit “From the Archives: The Role of the Art Critic.”

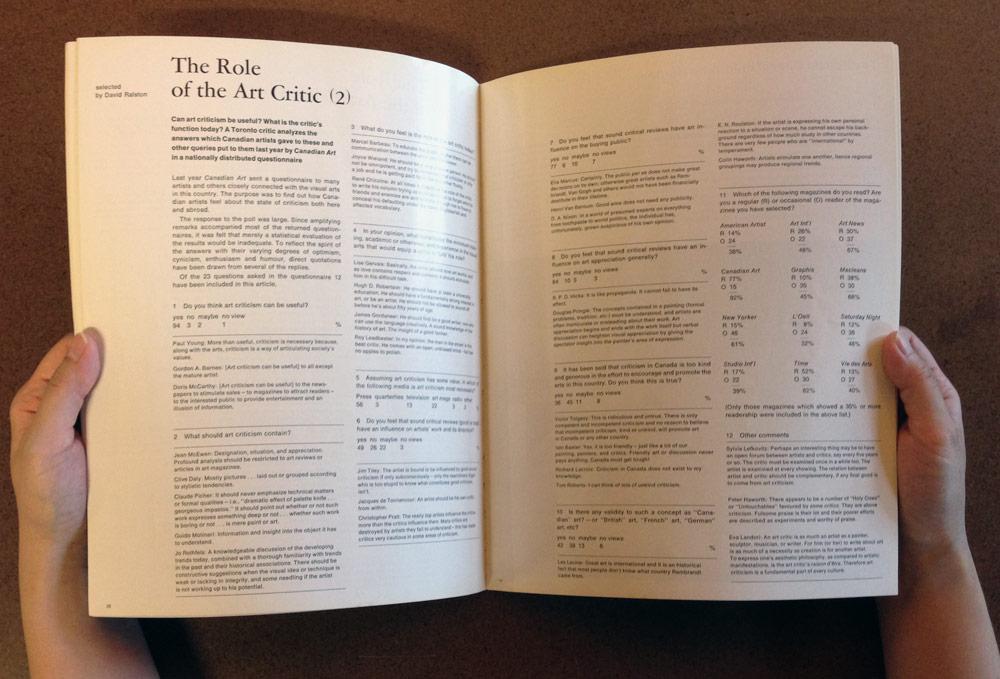

A broad survey about art criticism in the April 1966 issue of another publication also called Canadian Art.

A broad survey about art criticism in the April 1966 issue of another publication also called Canadian Art.